Alex Colville in 1843 Magazine:

Gazing at the Moon is an eternal human activity, one of the few things uniting caveman, king and commuter. Each has found something different in that lambent face. For Li Po, a lonely Tang dynasty poet, the Moon was a much-needed drinking buddy. For Holly Golightly, who serenaded it during the “Moon River” scene of “Breakfast at Tiffany’s”, it was a “huckleberry friend” who could whisk her away from her fire escape and her sorrows. By pretending to control a well-timed lunar eclipe, Columbus recruited it to terrify Native Americans into submission. Mussolini superstitiously feared sleeping in its light, and hid from it behind tightly drawn blinds. It would be a challenge for any museum to chronicle the long, complicated relationship humanity has with the Moon, but the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich, London has done it. For the 50th anniversary of the Apollo 11 Moon landing, the museum has placed relics from those nine remarkable days in July 1969 alongside cuneiform tablets, Ottoman pocket lunar-calendars, giant Victorian telescopes and instruments designed for India’s first lunar probe in 2008. This impressive exhibition tells the history of humanity’s fascination with this celestial body and looks to the future, as humans attempt once again to return to the Moon.

Gazing at the Moon is an eternal human activity, one of the few things uniting caveman, king and commuter. Each has found something different in that lambent face. For Li Po, a lonely Tang dynasty poet, the Moon was a much-needed drinking buddy. For Holly Golightly, who serenaded it during the “Moon River” scene of “Breakfast at Tiffany’s”, it was a “huckleberry friend” who could whisk her away from her fire escape and her sorrows. By pretending to control a well-timed lunar eclipe, Columbus recruited it to terrify Native Americans into submission. Mussolini superstitiously feared sleeping in its light, and hid from it behind tightly drawn blinds. It would be a challenge for any museum to chronicle the long, complicated relationship humanity has with the Moon, but the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich, London has done it. For the 50th anniversary of the Apollo 11 Moon landing, the museum has placed relics from those nine remarkable days in July 1969 alongside cuneiform tablets, Ottoman pocket lunar-calendars, giant Victorian telescopes and instruments designed for India’s first lunar probe in 2008. This impressive exhibition tells the history of humanity’s fascination with this celestial body and looks to the future, as humans attempt once again to return to the Moon.

The Moon was once the domain of the gods, who had placed this seemingly smooth orb in the heavens, the finishing touch to a perfectly ordered creation. The red of the blood Moon was a sign of divine imbalance that only humanity could correct: the Chinese banged mirrors, the Inca shouted and the Romans frantically waved burning torches.

More here.

In the early days of the run-up to the 2016 election, I was just beginning to prepare a class on whiteness to teach at Yale University, where I had been newly hired. Over the years, I had come to realize that I often did not share historical knowledge with the persons to whom I was speaking. “What’s redlining?” someone would ask. “George Washington freed his slaves?” someone else would inquire. But as I listened to Donald Trump’s inflammatory rhetoric during the campaign that spring, the class took on a new dimension. Would my students understand the long history that informed a comment like one Trump made when he announced his presidential candidacy? “When Mexico sends its people, they’re not sending their best,” he said. “They’re sending people that have lots of problems, and they’re bringing those problems with us. They’re bringing drugs. They’re bringing crime. They’re rapists.” When I heard those words, I wanted my students to track immigration laws in the United States. Would they connect the treatment of the undocumented with the treatment of Irish, Italian and Asian people over the centuries?

In the early days of the run-up to the 2016 election, I was just beginning to prepare a class on whiteness to teach at Yale University, where I had been newly hired. Over the years, I had come to realize that I often did not share historical knowledge with the persons to whom I was speaking. “What’s redlining?” someone would ask. “George Washington freed his slaves?” someone else would inquire. But as I listened to Donald Trump’s inflammatory rhetoric during the campaign that spring, the class took on a new dimension. Would my students understand the long history that informed a comment like one Trump made when he announced his presidential candidacy? “When Mexico sends its people, they’re not sending their best,” he said. “They’re sending people that have lots of problems, and they’re bringing those problems with us. They’re bringing drugs. They’re bringing crime. They’re rapists.” When I heard those words, I wanted my students to track immigration laws in the United States. Would they connect the treatment of the undocumented with the treatment of Irish, Italian and Asian people over the centuries? Walter Gropius was fond of making claims about The Bauhaus like the following: “Our guiding principle was that design is neither an intellectual nor a material affair, but simply an integral part of the stuff of life, necessary for everyone in a civilized society.” Idealistic and vague, perhaps to a fault, but one gets the point. Bauhaus design was never intended to be alienating. It was supposed to be the opposite. It was supposed to preserve the relative “health” of the craft traditions while marching boldly into a new era. It was supposed to help cure the potential wounds of modern life, wounds caused, initially, by the industrial revolution and its jarring impact on everything from the natural landscape to the material and design of our cutlery. Anti-alienation was really the one guiding intuition behind The Bauhaus as a school and then, more amorphously, as a general approach to architecture and design.

Walter Gropius was fond of making claims about The Bauhaus like the following: “Our guiding principle was that design is neither an intellectual nor a material affair, but simply an integral part of the stuff of life, necessary for everyone in a civilized society.” Idealistic and vague, perhaps to a fault, but one gets the point. Bauhaus design was never intended to be alienating. It was supposed to be the opposite. It was supposed to preserve the relative “health” of the craft traditions while marching boldly into a new era. It was supposed to help cure the potential wounds of modern life, wounds caused, initially, by the industrial revolution and its jarring impact on everything from the natural landscape to the material and design of our cutlery. Anti-alienation was really the one guiding intuition behind The Bauhaus as a school and then, more amorphously, as a general approach to architecture and design.

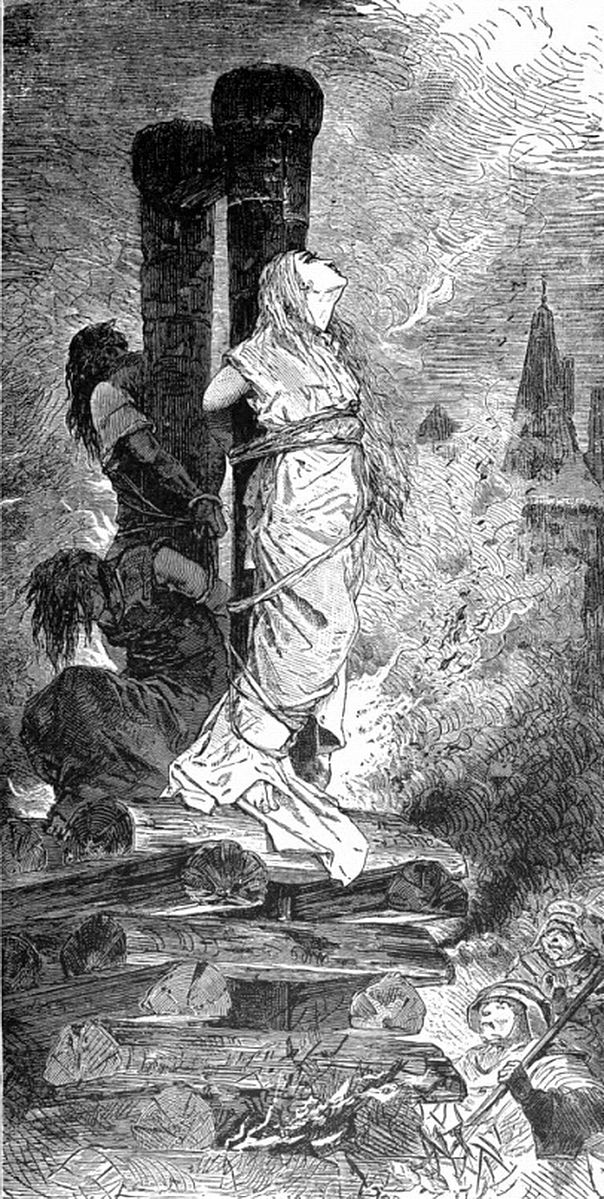

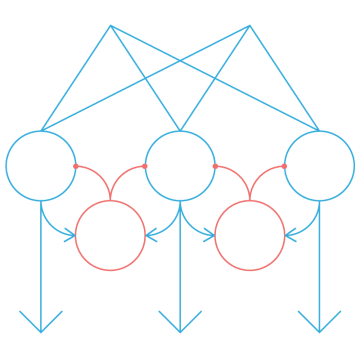

The theory of Darwinian cultural evolution is gaining currency in many parts of the socio-cultural sciences, but it remains contentious. Critics claim that the theory is either fundamentally mistaken or boils down to a fancy re-description of things we knew all along. We will argue that cultural Darwinism can indeed resolve long-standing socio-cultural puzzles; this is demonstrated through a cultural Darwinian analysis of the European witch persecutions. Two central and unresolved questions concerning witch-hunts will be addressed. From the fifteenth to the seventeenth centuries, a remarkable and highly specific concept of witchcraft was taking shape in Europe. The first question is: who constructed it? With hindsight, we can see that the concept contains many elements that appear to be intelligently designed to ensure the continuation of witch persecutions, such as the witches’ sabbat, the diabolical pact, nightly flight, and torture as a means of interrogation. The second question is: why did beliefs in witchcraft and witch-hunts persist and disseminate, despite the fact that, as many historians have concluded, no one appears to have substantially benefited from them? Historians have convincingly argued that witch-hunts were not inspired by some hidden agenda; persecutors genuinely believed in the threat of witchcraft to their communities. We propose that the apparent ‘design’ exhibited by concepts of witchcraft resulted from a Darwinian process of evolution, in which cultural variants that accidentally enhanced the reproduction of the witch-hunts were selected and accumulated. We argue that witch persecutions form a prime example of a ‘viral’ socio-cultural phenomenon that reproduces ‘selfishly’, even harming the interests of its human hosts.

The theory of Darwinian cultural evolution is gaining currency in many parts of the socio-cultural sciences, but it remains contentious. Critics claim that the theory is either fundamentally mistaken or boils down to a fancy re-description of things we knew all along. We will argue that cultural Darwinism can indeed resolve long-standing socio-cultural puzzles; this is demonstrated through a cultural Darwinian analysis of the European witch persecutions. Two central and unresolved questions concerning witch-hunts will be addressed. From the fifteenth to the seventeenth centuries, a remarkable and highly specific concept of witchcraft was taking shape in Europe. The first question is: who constructed it? With hindsight, we can see that the concept contains many elements that appear to be intelligently designed to ensure the continuation of witch persecutions, such as the witches’ sabbat, the diabolical pact, nightly flight, and torture as a means of interrogation. The second question is: why did beliefs in witchcraft and witch-hunts persist and disseminate, despite the fact that, as many historians have concluded, no one appears to have substantially benefited from them? Historians have convincingly argued that witch-hunts were not inspired by some hidden agenda; persecutors genuinely believed in the threat of witchcraft to their communities. We propose that the apparent ‘design’ exhibited by concepts of witchcraft resulted from a Darwinian process of evolution, in which cultural variants that accidentally enhanced the reproduction of the witch-hunts were selected and accumulated. We argue that witch persecutions form a prime example of a ‘viral’ socio-cultural phenomenon that reproduces ‘selfishly’, even harming the interests of its human hosts. The reason we pay happily for these manuals is straightforward, if a little sad. We’ve been convinced that we need them — that without them, we’d be lost. Readers aren’t drawn to in-depth arguments on punctuation and conjugation for the sheer fun of it; they’re sold on the promise of progress, of betterment. These books benefit from the dire misconception that they are for everyday people, when, in fact, they’re for editors and educators.

The reason we pay happily for these manuals is straightforward, if a little sad. We’ve been convinced that we need them — that without them, we’d be lost. Readers aren’t drawn to in-depth arguments on punctuation and conjugation for the sheer fun of it; they’re sold on the promise of progress, of betterment. These books benefit from the dire misconception that they are for everyday people, when, in fact, they’re for editors and educators. Contemporary technological anxiety—when not directed towards the internet wholesale—is just as often pitched against sound. We’ve recently started to ask what platform monopolies are doing to the quality of music, or whether Amazon is killing record (and book) stores, or if podcasts are further ensnaring us online, destroying our private thoughts. It’s enough, given his pedagogical wisdom, to make us wonder: What would Berger say?—about earbuds or

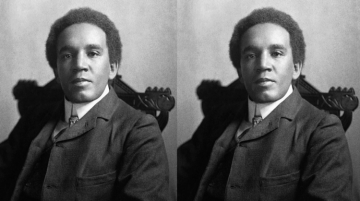

Contemporary technological anxiety—when not directed towards the internet wholesale—is just as often pitched against sound. We’ve recently started to ask what platform monopolies are doing to the quality of music, or whether Amazon is killing record (and book) stores, or if podcasts are further ensnaring us online, destroying our private thoughts. It’s enough, given his pedagogical wisdom, to make us wonder: What would Berger say?—about earbuds or  Coleridge-Taylor was deeply interested in both African and African-American melodies. A meeting with the American writer Paul Laurence Dunbar in 1896, for example, had let to a vocal work, African Romances, with the two of them deciding to put on a series of performances together. Another work, the Twenty-Four Negro Melodies for piano, was influenced by Dunbar’s work. “What Brahms has done for the Hungarian folk music,” Coleridge-Taylor wrote in the preface to the score, “Dvořák for the Bohemian, and Grieg for the Norwegian, I have tried to do for these Negro melodies.” But though the composer’s political consciousness had been informed by an abiding interest in pan-Africanism, though his explorations of his paternal ancestry had him briefly flirting with the idea of relocating to the United States, he primarily filtered the raw materials of black American and African music through a distinctly European sensibility, Brahms and Dvořák being his guiding lights. Coleridge-Taylor’s true métier was the realm of light English music, and as interest in that field diminished with the passing of the 20th century, with the decline of the amateur choruses that once would have taken up such repertoire, so too did an interest in his music. This was already true by 1912, the year the composer died from pneumonia, having collapsed at the West Croydon station, while waiting for a train.

Coleridge-Taylor was deeply interested in both African and African-American melodies. A meeting with the American writer Paul Laurence Dunbar in 1896, for example, had let to a vocal work, African Romances, with the two of them deciding to put on a series of performances together. Another work, the Twenty-Four Negro Melodies for piano, was influenced by Dunbar’s work. “What Brahms has done for the Hungarian folk music,” Coleridge-Taylor wrote in the preface to the score, “Dvořák for the Bohemian, and Grieg for the Norwegian, I have tried to do for these Negro melodies.” But though the composer’s political consciousness had been informed by an abiding interest in pan-Africanism, though his explorations of his paternal ancestry had him briefly flirting with the idea of relocating to the United States, he primarily filtered the raw materials of black American and African music through a distinctly European sensibility, Brahms and Dvořák being his guiding lights. Coleridge-Taylor’s true métier was the realm of light English music, and as interest in that field diminished with the passing of the 20th century, with the decline of the amateur choruses that once would have taken up such repertoire, so too did an interest in his music. This was already true by 1912, the year the composer died from pneumonia, having collapsed at the West Croydon station, while waiting for a train. Will the robots of the future be able to replicate human thought? Most engineers assume so with a casual fatalism: the rate of advance in artificial intelligence (AI) is so rapid that it is only a matter of time before robots indistinguishable from human beings are built. Will the robots of the future surpass and then subordinate their creators? Some of the initiated believe so. This impending apocalypse has a name – “the singularity” – and is confidently expected in some quarters as soon as 2045.

Will the robots of the future be able to replicate human thought? Most engineers assume so with a casual fatalism: the rate of advance in artificial intelligence (AI) is so rapid that it is only a matter of time before robots indistinguishable from human beings are built. Will the robots of the future surpass and then subordinate their creators? Some of the initiated believe so. This impending apocalypse has a name – “the singularity” – and is confidently expected in some quarters as soon as 2045. At each instant, our senses gather oodles of sensory information, yet somehow our brains reduce that fire hose of input to simple realities: A car is honking. A bluebird is flying.

At each instant, our senses gather oodles of sensory information, yet somehow our brains reduce that fire hose of input to simple realities: A car is honking. A bluebird is flying. RECENTLY

RECENTLY Survivor camps established after shipwrecks provide fascinating data about the societies that groups of people make when it’s left up to them, about how and why social order might vary, and about what arrangements are the most conducive to peace and survival. An archipelago of shipwrecks, formed over centuries, more or less at random, has resulted in people participating, unintentionally, in multiple trials of this experiment.

Survivor camps established after shipwrecks provide fascinating data about the societies that groups of people make when it’s left up to them, about how and why social order might vary, and about what arrangements are the most conducive to peace and survival. An archipelago of shipwrecks, formed over centuries, more or less at random, has resulted in people participating, unintentionally, in multiple trials of this experiment. ANDY FITCH: A New Foreign Policy takes the sustainable-development framework (prioritizing smart-infrastructure investments, significantly expanded renewable-energy production, more equitable income distribution, tech-fostering education) that you have outlined for various domestic contexts, and applies this to a broader international arena. Could you introduce that sustainable-development approach here by sketching how its basic principles might overlap whether one adopts a domestic- or global-policy vantage — and also by pointing to where this new book might need to provide a slightly different emphasis, argument, agenda? Specifically picking up this book’s subtitle, could you start to sketch how the follies of American-exceptionalist approaches (both at present, and amid a longer arc of US history) might contribute both to the necessity and to the difficulty of adopting this sustainable-development model as a guiding frame for today’s foreign policy?

ANDY FITCH: A New Foreign Policy takes the sustainable-development framework (prioritizing smart-infrastructure investments, significantly expanded renewable-energy production, more equitable income distribution, tech-fostering education) that you have outlined for various domestic contexts, and applies this to a broader international arena. Could you introduce that sustainable-development approach here by sketching how its basic principles might overlap whether one adopts a domestic- or global-policy vantage — and also by pointing to where this new book might need to provide a slightly different emphasis, argument, agenda? Specifically picking up this book’s subtitle, could you start to sketch how the follies of American-exceptionalist approaches (both at present, and amid a longer arc of US history) might contribute both to the necessity and to the difficulty of adopting this sustainable-development model as a guiding frame for today’s foreign policy? There’s no way to know, of course, if all this happened as Gilot says it did. (Lake said that she had “total recall,” a claim that tends to raise rather than allay suspicions.) She has the memoirist’s prerogative—this is how I remember it—and Picasso’s tyranny and brilliance are hardly in dispute. The bigger mystery is Gilot; the self in her self-portrait can be hard to see behind the lacquered irony and reserve. She goes along with Picasso’s more outlandish demands and schemes, but, she tells us, “not at all for his reasons.” Her dissent is withering and sarcastic rather than furious; like other women of her generation who pointedly overlooked the bad behavior of their husbands, she is concerned with preserving her own dignity. When she is seven months pregnant with Paloma, her doctor (an obstetrician this time) tells her that she is in danger; the labor has to be induced immediately. Alas, this is inconvenient for Picasso, who is due to be at a World Peace Conference elsewhere in Paris the same day.

There’s no way to know, of course, if all this happened as Gilot says it did. (Lake said that she had “total recall,” a claim that tends to raise rather than allay suspicions.) She has the memoirist’s prerogative—this is how I remember it—and Picasso’s tyranny and brilliance are hardly in dispute. The bigger mystery is Gilot; the self in her self-portrait can be hard to see behind the lacquered irony and reserve. She goes along with Picasso’s more outlandish demands and schemes, but, she tells us, “not at all for his reasons.” Her dissent is withering and sarcastic rather than furious; like other women of her generation who pointedly overlooked the bad behavior of their husbands, she is concerned with preserving her own dignity. When she is seven months pregnant with Paloma, her doctor (an obstetrician this time) tells her that she is in danger; the labor has to be induced immediately. Alas, this is inconvenient for Picasso, who is due to be at a World Peace Conference elsewhere in Paris the same day. Mary Gabriel’s Ninth Street Women charts the rise of five female Abstract Expressionist painters in New York – Lee Krasner, Elaine de Kooning, Grace Hartigan, Joan Mitchell and Helen Frankenthaler – which is a bold move, since all of these women expressed vehement dislike of critics who used their gender as an ordering conceit. To be labelled a “lady painter” or the “wife of the artist” was an exoticization at best, a dismissal at worst. In 1957, Hartigan, Mitchell and Frankenthaler were featured in Life magazine’s feature “Women Artists in Ascendance”, photographed in their studios with their work. Each looks steadily at the camera. They knew the possible benefits of exposure, but they didn’t have to smile. In her introduction, Gabriel tells us that what she has written, “through the biographies of five remarkable women, is the story of a cultural revolution that occurred between the years of 1929 and 1959 as it arose out of the Depression and the Second World War, developed amid the Cold War and McCarthyism, and declined through the early boom years of America’s consumer culture”. Well, yes, but beyond these larger, sweeping assessments of society and gender there is a lot more.

Mary Gabriel’s Ninth Street Women charts the rise of five female Abstract Expressionist painters in New York – Lee Krasner, Elaine de Kooning, Grace Hartigan, Joan Mitchell and Helen Frankenthaler – which is a bold move, since all of these women expressed vehement dislike of critics who used their gender as an ordering conceit. To be labelled a “lady painter” or the “wife of the artist” was an exoticization at best, a dismissal at worst. In 1957, Hartigan, Mitchell and Frankenthaler were featured in Life magazine’s feature “Women Artists in Ascendance”, photographed in their studios with their work. Each looks steadily at the camera. They knew the possible benefits of exposure, but they didn’t have to smile. In her introduction, Gabriel tells us that what she has written, “through the biographies of five remarkable women, is the story of a cultural revolution that occurred between the years of 1929 and 1959 as it arose out of the Depression and the Second World War, developed amid the Cold War and McCarthyism, and declined through the early boom years of America’s consumer culture”. Well, yes, but beyond these larger, sweeping assessments of society and gender there is a lot more. At a time where politicians across the world are calling for ever more secure borders, there are books whose mere existence feels radical. Afropean: Notes from Black Europe, by Johny Pitts, feels like one such publication. It is the story of the Sheffield-born author’s travel from his home town across the Continent, visiting several of its major cities and connecting – or not – with people of African heritage as he goes. Crucially, it is also the story of Pitts’s internal journey, to find where he, a working-class, mixed-race man from the north of England, might fit most comfortably within Europe’s complex past and its possibly chaotic future.

At a time where politicians across the world are calling for ever more secure borders, there are books whose mere existence feels radical. Afropean: Notes from Black Europe, by Johny Pitts, feels like one such publication. It is the story of the Sheffield-born author’s travel from his home town across the Continent, visiting several of its major cities and connecting – or not – with people of African heritage as he goes. Crucially, it is also the story of Pitts’s internal journey, to find where he, a working-class, mixed-race man from the north of England, might fit most comfortably within Europe’s complex past and its possibly chaotic future. Remember when everyone left doors unlocked and borrowed cups of sugar? No? Then this richly researched history of community may well appeal. Jon Lawrence uncovers the reality behind romantic cliches of our postwar past. He convincingly suggests that the real history of community is one in which people have combined solidarity with self-reliance and privacy.

Remember when everyone left doors unlocked and borrowed cups of sugar? No? Then this richly researched history of community may well appeal. Jon Lawrence uncovers the reality behind romantic cliches of our postwar past. He convincingly suggests that the real history of community is one in which people have combined solidarity with self-reliance and privacy. Personalized medicine. Precision medicine. Genomic medicine. Individualized medicine. All of these phrases strive to express a similar vision—a reality where physicians treat based on each patient’s unique biology. The concept is poised to revolutionize clinical and preventive care. But even as the technologies helping to birth this new breed of medicine mature, the semantics surrounding the phenomenon are still experiencing growing pains. So, what should we call it? For a long time, “personalized medicine” was the preferred nomenclature. In the popular press especially, this was (and often still is) the go-to phrase to describe the medical paradigm shift that is underway. But about eight years ago, a committee convened by the director of the National Institutes of Health

Personalized medicine. Precision medicine. Genomic medicine. Individualized medicine. All of these phrases strive to express a similar vision—a reality where physicians treat based on each patient’s unique biology. The concept is poised to revolutionize clinical and preventive care. But even as the technologies helping to birth this new breed of medicine mature, the semantics surrounding the phenomenon are still experiencing growing pains. So, what should we call it? For a long time, “personalized medicine” was the preferred nomenclature. In the popular press especially, this was (and often still is) the go-to phrase to describe the medical paradigm shift that is underway. But about eight years ago, a committee convened by the director of the National Institutes of Health