Hope Reese in UnDark:

Patricia S. Churchland is a key figure in the field of neurophilosophy, which employs a multidisciplinary lens to examine how neurobiology contributes to philosophical and ethical thinking. In her new book, “Conscience: The Origins of Moral Intuition,” Churchland makes the case that neuroscience, evolution, and biology are essential to understanding moral decision-making and how we behave in social environments.

Patricia S. Churchland is a key figure in the field of neurophilosophy, which employs a multidisciplinary lens to examine how neurobiology contributes to philosophical and ethical thinking. In her new book, “Conscience: The Origins of Moral Intuition,” Churchland makes the case that neuroscience, evolution, and biology are essential to understanding moral decision-making and how we behave in social environments.

The way we reach moral conclusions, she asserts, has a lot more to do with our neural circuitry than we realize. We are fundamentally hard-wired to form attachments, for instance, which greatly influence our moral decision-making. Also, our brains are constantly using reinforcement learning — observing consequences after specific actions and adjusting our behavior accordingly.

Churchland, who teaches philosophy at the University of California, San Diego, also presents research showing that our individual neuro-architecture is heavily influenced by genetics: political attitudes, for instance, are 40 to 50 percent heritable, recent scientific studies suggest.

While some critics are skeptical that neuroscience plays an important role in morality, and argue that Churchland’s brand of neurophilosophy undermines widely accepted philosophical principles, she insists that she is a philosopher, first and foremost, and that she isn’t abandoning traditional philosophical inquiry as much as expanding its scope.

More here.

There are times when a dilemma that seems like agony in adolescence can not only provide the basis for a prestigious career, but also lead to a profound shift in the world of ideas. Thus it is that the predicament faced by the 17-year-old Gregory Bateson, following his brother’s suicide in 1922, turns out to be extremely relevant to us today, for it eventually led him to revolutionise the study of anthropology, bring communication theory to psychoanalysis (thus undermining the Freudian model), invent the concept of the ‘double bind’, and make one of the first coherent, scientifically and philosophically argued pleas for a holistic approach to the world’s environmental crisis. Seeking to condense Bateson’s work into one core concept, one can say that, above all, he proposed a paradigm shift in the way we think of ourselves as purposeful, decision-making actors in the world.

There are times when a dilemma that seems like agony in adolescence can not only provide the basis for a prestigious career, but also lead to a profound shift in the world of ideas. Thus it is that the predicament faced by the 17-year-old Gregory Bateson, following his brother’s suicide in 1922, turns out to be extremely relevant to us today, for it eventually led him to revolutionise the study of anthropology, bring communication theory to psychoanalysis (thus undermining the Freudian model), invent the concept of the ‘double bind’, and make one of the first coherent, scientifically and philosophically argued pleas for a holistic approach to the world’s environmental crisis. Seeking to condense Bateson’s work into one core concept, one can say that, above all, he proposed a paradigm shift in the way we think of ourselves as purposeful, decision-making actors in the world. Last Tuesday, the House of Representatives passed a resolution,

Last Tuesday, the House of Representatives passed a resolution,  If the fashionable idea of the 1980s was upward mobility, then the buzzword of this decade is authenticity. This ruling ideal of being true to yourself and “keeping it real” is rarely criticised. But what if the message deters individual transformation and encourages everyone to stay in their place? Is the ethic of authenticity in some ways more conservative than the Thatcherite yuppie message it replaced? I think it’s time to consider how authenticity stands in the way of progress and aspiration. We’ll begin with moral philosophy, touch on my journey from working-class kid to university academic, and consider everything from Pride to Boris Johnson and Donald Trump. We’ll even consider why authenticity can lead to problems getting up in the morning. Here we go. Imagine your partner asks “can you drive to Peterborough to pick up my passport?” and you reply, as positively as you can, “I’d be happy to do that.” You’re not really happy about it: you want to help, but you’d much rather come straight home. You could say that in this moment you are being inauthentic. In fact, we can imagine your partner calling you out on it: don’t say you are happy to if you are not. Perhaps an argument ensues.

If the fashionable idea of the 1980s was upward mobility, then the buzzword of this decade is authenticity. This ruling ideal of being true to yourself and “keeping it real” is rarely criticised. But what if the message deters individual transformation and encourages everyone to stay in their place? Is the ethic of authenticity in some ways more conservative than the Thatcherite yuppie message it replaced? I think it’s time to consider how authenticity stands in the way of progress and aspiration. We’ll begin with moral philosophy, touch on my journey from working-class kid to university academic, and consider everything from Pride to Boris Johnson and Donald Trump. We’ll even consider why authenticity can lead to problems getting up in the morning. Here we go. Imagine your partner asks “can you drive to Peterborough to pick up my passport?” and you reply, as positively as you can, “I’d be happy to do that.” You’re not really happy about it: you want to help, but you’d much rather come straight home. You could say that in this moment you are being inauthentic. In fact, we can imagine your partner calling you out on it: don’t say you are happy to if you are not. Perhaps an argument ensues. For a few months in the first half of 2019, Chris Payze started each morning at home in Queensland, Australia, by jotting down answers to a series of questions. What time did I go to bed? How many times did I wake up? Speaking to The Scientist this April, 71-year-old Payze said she’d gotten “really into the groove” of this daily routine. “It only takes me about five minutes.” She recorded the information for a trial of melatonin, a hormone that regulates sleep-wake cycles and is often taken orally as a sleep aid, although it’s not clear how well it works. Payze has Parkinson’s disease, and for the last couple years, she, like many people with the condition, has been dealing with insomnia. “I just have awful trouble sleeping at night,” she explains. While she doesn’t feel sleep-deprived, the interrupted sleep “is just annoying me. I’d love to sleep through the night one night.”

For a few months in the first half of 2019, Chris Payze started each morning at home in Queensland, Australia, by jotting down answers to a series of questions. What time did I go to bed? How many times did I wake up? Speaking to The Scientist this April, 71-year-old Payze said she’d gotten “really into the groove” of this daily routine. “It only takes me about five minutes.” She recorded the information for a trial of melatonin, a hormone that regulates sleep-wake cycles and is often taken orally as a sleep aid, although it’s not clear how well it works. Payze has Parkinson’s disease, and for the last couple years, she, like many people with the condition, has been dealing with insomnia. “I just have awful trouble sleeping at night,” she explains. While she doesn’t feel sleep-deprived, the interrupted sleep “is just annoying me. I’d love to sleep through the night one night.” No, but seriously. We considered other very good series for this honor but kept coming back to Fleabag, the same way Fleabag, the character created and played by the magnificent Phoebe Waller-Bridge, keeps going back to the Priest during the perfect second season of this fantastic series. The attraction can’t be denied.

No, but seriously. We considered other very good series for this honor but kept coming back to Fleabag, the same way Fleabag, the character created and played by the magnificent Phoebe Waller-Bridge, keeps going back to the Priest during the perfect second season of this fantastic series. The attraction can’t be denied. When cells are no longer needed, they die with what can only be called great dignity,” Bill Bryson wrote in A Short History of Nearly Everything. The received wisdom has long been that this march toward oblivion, once sufficiently advanced, cannot be reversed. But as science charts the contours of cellular function in ever-greater detail, a more fluid conception of cellular life and death has begun to gain the upper hand.

When cells are no longer needed, they die with what can only be called great dignity,” Bill Bryson wrote in A Short History of Nearly Everything. The received wisdom has long been that this march toward oblivion, once sufficiently advanced, cannot be reversed. But as science charts the contours of cellular function in ever-greater detail, a more fluid conception of cellular life and death has begun to gain the upper hand. “I can’t imagine him doing anything that’s not good for the country.” In an

“I can’t imagine him doing anything that’s not good for the country.” In an  Here’s a thought. Teen angst, once regarded as stubbornly generic, is actually a product of each person’s unique circumstances: gender, race, class, era. Angst is universal, but the content of it is particular. This might explain why Holden Caulfield, once the universal everyteen, does not speak to this generation in the way he’s spoken to young people in the past.

Here’s a thought. Teen angst, once regarded as stubbornly generic, is actually a product of each person’s unique circumstances: gender, race, class, era. Angst is universal, but the content of it is particular. This might explain why Holden Caulfield, once the universal everyteen, does not speak to this generation in the way he’s spoken to young people in the past.

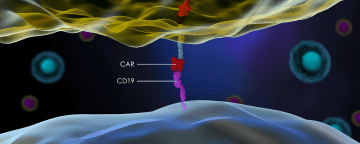

Despite the recent approval of two cancer therapies that use CAR T cells to treat lymphoma, 25 percent of eligible patients still choose to enter clinical trials instead of undergoing the available treatments. That’s according to insurance claims analyzed by health care consulting firm Vizient,

Despite the recent approval of two cancer therapies that use CAR T cells to treat lymphoma, 25 percent of eligible patients still choose to enter clinical trials instead of undergoing the available treatments. That’s according to insurance claims analyzed by health care consulting firm Vizient,

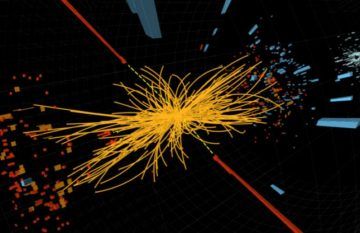

The trickiest part of hunting for new elementary particles is sifting through the massive amounts of data to find telltale patterns, or “signatures,” for those particles—or, ideally, weird patterns that don’t fit any known particle, an indication of new physics beyond the so-called

The trickiest part of hunting for new elementary particles is sifting through the massive amounts of data to find telltale patterns, or “signatures,” for those particles—or, ideally, weird patterns that don’t fit any known particle, an indication of new physics beyond the so-called  The British quit India in 1947. A blood-soaked partition had torn the subcontinent into two states that became the Islamic Republic of Pakistan and the Republic of India, the latter comprising many faiths but secular. Or attempting to be: India was left with not so much a separation of state and religion as an intention to embrace all traditions evenly.

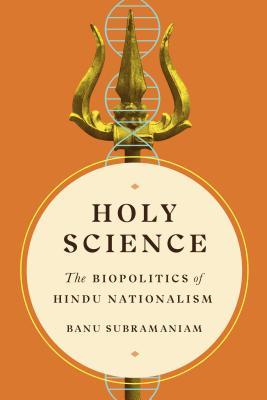

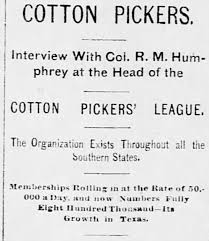

The British quit India in 1947. A blood-soaked partition had torn the subcontinent into two states that became the Islamic Republic of Pakistan and the Republic of India, the latter comprising many faiths but secular. Or attempting to be: India was left with not so much a separation of state and religion as an intention to embrace all traditions evenly. It has not always been the case, after all, that American academics saw populism in terms of “identity.” In the 1920s, American historians could still look back fondly on the Populist episode as one of the many episodes in the age-long American class struggle. To followers of Charles A. Beard, doyen of the Progressive School in American History, Populism represented the last revolt of the small freeholding class, who, while being crushed by the advent of the industrial society, protested their new market-dependency by uniting on class lines. Other writers in this tradition, such as Vernon Parrington or John Hicks, shared their sentiments. Parrington’s Main Currents of American Thought (1927) cast “populism” as the revolt of small property-holders upholding the Jeffersonian ideal, sharing a pedigree which went back to the Founders’ Age. John Hicks’ classic The Populist Revolt (1931) tracked a similar genealogy, trying to show how the aims of the original Populist movement were translated into the working-class agitation of the incipient New Deal. Another classic of Populist historiography, Comer Vann Woodward’s Tom Watson: Agrarian Rebel (1937), made a similar diagnosis of the economic character of the “agrarian crusade” which took Southern states by storm in the 1880s and 1890s.

It has not always been the case, after all, that American academics saw populism in terms of “identity.” In the 1920s, American historians could still look back fondly on the Populist episode as one of the many episodes in the age-long American class struggle. To followers of Charles A. Beard, doyen of the Progressive School in American History, Populism represented the last revolt of the small freeholding class, who, while being crushed by the advent of the industrial society, protested their new market-dependency by uniting on class lines. Other writers in this tradition, such as Vernon Parrington or John Hicks, shared their sentiments. Parrington’s Main Currents of American Thought (1927) cast “populism” as the revolt of small property-holders upholding the Jeffersonian ideal, sharing a pedigree which went back to the Founders’ Age. John Hicks’ classic The Populist Revolt (1931) tracked a similar genealogy, trying to show how the aims of the original Populist movement were translated into the working-class agitation of the incipient New Deal. Another classic of Populist historiography, Comer Vann Woodward’s Tom Watson: Agrarian Rebel (1937), made a similar diagnosis of the economic character of the “agrarian crusade” which took Southern states by storm in the 1880s and 1890s. The obituary reads: Author, Protégée of Bellow’s. Two defining characteristics of a life. Equally weighted, side by side. Bette Howland has been known, when she was known, by her proximity to male greatness. Just as Sylvia Plath is rarely mentioned without the appendage of Ted Hughes, Howland’s name, and her writing, reach us within the context of her position as protégée, friend to, and occasional lover of Saul Bellow.

The obituary reads: Author, Protégée of Bellow’s. Two defining characteristics of a life. Equally weighted, side by side. Bette Howland has been known, when she was known, by her proximity to male greatness. Just as Sylvia Plath is rarely mentioned without the appendage of Ted Hughes, Howland’s name, and her writing, reach us within the context of her position as protégée, friend to, and occasional lover of Saul Bellow. It took more than a hundred years, but physicists finally woke up, looked quantum mechanics into the face – and realized with bewilderment they barely know the theory they’ve been married to for so long. Gone are the days of “shut up and calculate”; the foundations of quantum mechanics are en vogue again.

It took more than a hundred years, but physicists finally woke up, looked quantum mechanics into the face – and realized with bewilderment they barely know the theory they’ve been married to for so long. Gone are the days of “shut up and calculate”; the foundations of quantum mechanics are en vogue again.