Andrew Sullivan in New York Magazine:

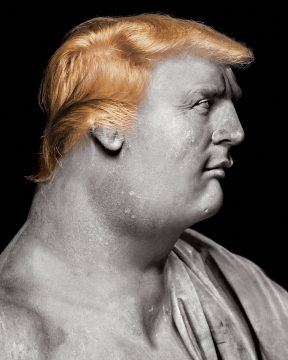

Well, we now have a solid record of what Trump has said and done. And it fits few modern templates exactly. He is no Pinochet nor Hitler, no Nixon nor Clinton. His emergence as a cultish strongman in a constitutional democracy who believes he has Article 2 sanction to do “whatever I want” — as he boasted, just casually, last month — seems to have few precedents.

Well, we now have a solid record of what Trump has said and done. And it fits few modern templates exactly. He is no Pinochet nor Hitler, no Nixon nor Clinton. His emergence as a cultish strongman in a constitutional democracy who believes he has Article 2 sanction to do “whatever I want” — as he boasted, just casually, last month — seems to have few precedents.

But zoom out a little more and one obvious and arguably apposite parallel exists: the Roman Republic, whose fate the Founding Fathers were extremely conscious of when they designed the U.S. Constitution. That tremendously successful republic began, like ours, by throwing off monarchy, and went on to last for the better part of 500 years. It practiced slavery as an integral and fast-growing part of its economy. It became embroiled in bitter and bloody civil wars, even as its territory kept expanding and its population took off. It won its own hot-and-cold war with its original nemesis, Carthage, bringing it into unexpected dominance over the entire Mediterranean as well as the whole Italian peninsula and Spain.

And the unprecedented wealth it acquired by essentially looting or taxing every city and territory it won and occupied soon created not just the first superpower but a superwealthy micro-elite — a one percent of its day — that used its money to control the political process and, over time, more to advance its own interests than the public good.

More here.

The current champion of heavyweight cinema, who vacillates between gallery and traditional cinematic presentation, must be the Chinese documentarian Wang Bing, who broke out internationally with his first film Tie Xi Qu: West of the Tracks (2003) and has subsequently produced the fourteen-hour Crude Oil (2008)—premiered as an installation at the 2008 International Film Festival Rotterdam—as well as the nearly nine-hour Dead Souls (2018). Andrew Chan, writing for Film Comment in 2016, distilled the role of duration in Wang’s work, writing, “Wang’s durational extremes do not just carry with them the weight of history and the inertia of the present; they also suggest that we as viewers might repay the gift of his subjects’ nakedness with our own sustained submission.” Chan is writing specifically about Wang’s 2013 ‘Til Madness Do Us Part, a nearly four-hour film that takes place almost entirely inside a dismal, crumbling mental institution doing double-duty as a lock-up for political undesirables. “Time in these films does not embrace, it provokes,” Chan continues, with further reference to West of the Tracks. “It’s felt as sacrifice and labor. And the aim is to make us earn, as if such a thing were possible, the right to lay eyes on humiliations that are at once collectively borne and unbearably private.”

The current champion of heavyweight cinema, who vacillates between gallery and traditional cinematic presentation, must be the Chinese documentarian Wang Bing, who broke out internationally with his first film Tie Xi Qu: West of the Tracks (2003) and has subsequently produced the fourteen-hour Crude Oil (2008)—premiered as an installation at the 2008 International Film Festival Rotterdam—as well as the nearly nine-hour Dead Souls (2018). Andrew Chan, writing for Film Comment in 2016, distilled the role of duration in Wang’s work, writing, “Wang’s durational extremes do not just carry with them the weight of history and the inertia of the present; they also suggest that we as viewers might repay the gift of his subjects’ nakedness with our own sustained submission.” Chan is writing specifically about Wang’s 2013 ‘Til Madness Do Us Part, a nearly four-hour film that takes place almost entirely inside a dismal, crumbling mental institution doing double-duty as a lock-up for political undesirables. “Time in these films does not embrace, it provokes,” Chan continues, with further reference to West of the Tracks. “It’s felt as sacrifice and labor. And the aim is to make us earn, as if such a thing were possible, the right to lay eyes on humiliations that are at once collectively borne and unbearably private.”

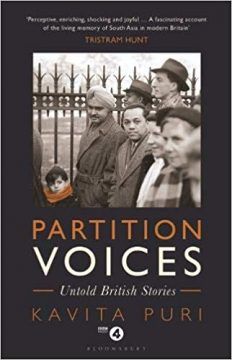

A Britain without the South Asian British is now almost unthinkable. With a few exceptions – farming, fishing and the armed forces spring to mind – there are few sectors of UK life where the descendants of South Asian immigrants are not prominent. Kavita Puri, for example, author of the harrowing Partition Voices, is a distinguished broadcaster whose father, Ravi, relocated from Delhi to Middlesbrough in 1959. The Puri family had lived originally in Lahore. But while the Puris were Hindu, the majority of Lahoris were Muslim. Under the terms of the 1947 partition plan, Lahore became part of Pakistan. The Puri family, in order to survive the carnage that ensued, had to flee across the border to the new Indian state, ending up in Delhi.

A Britain without the South Asian British is now almost unthinkable. With a few exceptions – farming, fishing and the armed forces spring to mind – there are few sectors of UK life where the descendants of South Asian immigrants are not prominent. Kavita Puri, for example, author of the harrowing Partition Voices, is a distinguished broadcaster whose father, Ravi, relocated from Delhi to Middlesbrough in 1959. The Puri family had lived originally in Lahore. But while the Puris were Hindu, the majority of Lahoris were Muslim. Under the terms of the 1947 partition plan, Lahore became part of Pakistan. The Puri family, in order to survive the carnage that ensued, had to flee across the border to the new Indian state, ending up in Delhi. It matters that the first patients were identical twins. Nancy and Barbara Lowry were six years old, dark-eyed and dark-haired, with eyebrow-skimming bangs. Sometime in the spring of 1960, Nancy fell ill. Her blood counts began to fall; her pediatricians noted that she was anemic. A biopsy revealed that she had a condition called aplastic anemia, a form of bone-marrow failure. The marrow produces blood cells, which need regular replenishing, and Nancy’s was rapidly shutting down. The origins of this illness are often mysterious, but in its typical form the spaces where young blood cells are supposed to be formed gradually fill up with globules of white fat. Barbara, just as mysteriously, was completely healthy. The Lowrys lived in Tacoma, a leafy, rain-slicked city near Seattle. At Seattle’s University of Washington hospital, where Nancy was being treated, the doctors had no clue what to do next. So they called a physician-scientist named E. Donnall Thomas, at the hospital in Cooperstown, New York, asking for help.

It matters that the first patients were identical twins. Nancy and Barbara Lowry were six years old, dark-eyed and dark-haired, with eyebrow-skimming bangs. Sometime in the spring of 1960, Nancy fell ill. Her blood counts began to fall; her pediatricians noted that she was anemic. A biopsy revealed that she had a condition called aplastic anemia, a form of bone-marrow failure. The marrow produces blood cells, which need regular replenishing, and Nancy’s was rapidly shutting down. The origins of this illness are often mysterious, but in its typical form the spaces where young blood cells are supposed to be formed gradually fill up with globules of white fat. Barbara, just as mysteriously, was completely healthy. The Lowrys lived in Tacoma, a leafy, rain-slicked city near Seattle. At Seattle’s University of Washington hospital, where Nancy was being treated, the doctors had no clue what to do next. So they called a physician-scientist named E. Donnall Thomas, at the hospital in Cooperstown, New York, asking for help. Kary Mullis, whose invention of the polymerase chain reaction technique earned him the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1993, died of pneumonia on August 7, according to

Kary Mullis, whose invention of the polymerase chain reaction technique earned him the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1993, died of pneumonia on August 7, according to  Climate scientists’ worst-case scenarios back in 2007, the first year the Northwest Passage became navigable without an icebreaker (today, you can book a cruise through it), have all been overtaken by the unforeseen acceleration of events. No one imagined that twelve years later the United Nations would report that we have just twelve years left to avert global catastrophe, which would involve cutting fossil-fuel use nearly by half. Since 2007, the UN now says, we’ve done everything wrong. New coal plants built since the 2015 Paris climate agreement have already doubled the equivalent coal-energy output of Russia and Japan, and 260 more are underway.

Climate scientists’ worst-case scenarios back in 2007, the first year the Northwest Passage became navigable without an icebreaker (today, you can book a cruise through it), have all been overtaken by the unforeseen acceleration of events. No one imagined that twelve years later the United Nations would report that we have just twelve years left to avert global catastrophe, which would involve cutting fossil-fuel use nearly by half. Since 2007, the UN now says, we’ve done everything wrong. New coal plants built since the 2015 Paris climate agreement have already doubled the equivalent coal-energy output of Russia and Japan, and 260 more are underway. The recent revolutions in Algeria and Sudan remind us that bottom-up movements of people power can create sweeping political transformations. They did this in part by mobilizing huge numbers of active protestors—

The recent revolutions in Algeria and Sudan remind us that bottom-up movements of people power can create sweeping political transformations. They did this in part by mobilizing huge numbers of active protestors— The Hindu-supremacist government of

The Hindu-supremacist government of  Writers have their pet themes, favorite words, stubborn obsessions. But their signature, the essence of their style, is felt someplace deeper — at the level of pulse. Style is first felt in rhythm and cadence, from how sentences build and bend, sag or snap. Style, I’d argue, is 90 percent punctuation.

Writers have their pet themes, favorite words, stubborn obsessions. But their signature, the essence of their style, is felt someplace deeper — at the level of pulse. Style is first felt in rhythm and cadence, from how sentences build and bend, sag or snap. Style, I’d argue, is 90 percent punctuation. One of the explanations for the rise of populist nationalist myths today goes back to the complicated dynamics between the individual and society, and between reason and fantasy. The thinker who might help us understand our current political storms is no other than Sigmund Freud. Freud is best known for his more controversial theories on sexuality. But we need not buy Freudian mechanics or his clinical theories. Enough of value remains without Oedipus. Freudian theory explores the tension between unconscious desires and the controlling ego, whose rational faculties, while fallible, may be marshalled to scrutinise our emotional drives. On this account, the freedom that humans possess rests solely in recognising and controlling fantasies and the passions that accompany them. With such awareness we are, at least, in a better position to judge and direct our actions – mitigating those that are destructive and strengthening the beneficial. This isn’t a new idea for western philosophy, and it goes at least as far back as Plato and Aristotle.

One of the explanations for the rise of populist nationalist myths today goes back to the complicated dynamics between the individual and society, and between reason and fantasy. The thinker who might help us understand our current political storms is no other than Sigmund Freud. Freud is best known for his more controversial theories on sexuality. But we need not buy Freudian mechanics or his clinical theories. Enough of value remains without Oedipus. Freudian theory explores the tension between unconscious desires and the controlling ego, whose rational faculties, while fallible, may be marshalled to scrutinise our emotional drives. On this account, the freedom that humans possess rests solely in recognising and controlling fantasies and the passions that accompany them. With such awareness we are, at least, in a better position to judge and direct our actions – mitigating those that are destructive and strengthening the beneficial. This isn’t a new idea for western philosophy, and it goes at least as far back as Plato and Aristotle. In Footsteps: Adventures of a Romantic Biographer, Richard Holmes described how, aged 18, he followed the route taken by Robert Louis Stevenson and his donkey almost 100 years earlier as they walked through the Massif Central in France. Sleeping, as Stevenson did, beneath the stars, bathing in rivers, and feeling half mad on the excess of liberty, Holmes learned that his vocation was to live like a ghost crab in another man’s shell. No one has described better the strange and obsessive nature of biographical pursuit, and the business of “footstepping” has since become associated with the Holmesian style of method-biography, in which the biographical subject returns from the dead with a palpable physical presence.

In Footsteps: Adventures of a Romantic Biographer, Richard Holmes described how, aged 18, he followed the route taken by Robert Louis Stevenson and his donkey almost 100 years earlier as they walked through the Massif Central in France. Sleeping, as Stevenson did, beneath the stars, bathing in rivers, and feeling half mad on the excess of liberty, Holmes learned that his vocation was to live like a ghost crab in another man’s shell. No one has described better the strange and obsessive nature of biographical pursuit, and the business of “footstepping” has since become associated with the Holmesian style of method-biography, in which the biographical subject returns from the dead with a palpable physical presence.

Marshall Sahlins in Counterpunch:

Marshall Sahlins in Counterpunch: The late Anges Heller in Public Seminar:

The late Anges Heller in Public Seminar: Joy James in Boston Review:

Joy James in Boston Review: