Daniel Markovits in The Atlantic:

In the summer of 1987, I graduated from a public high school in Austin, Texas, and headed northeast to attend Yale. I then spent nearly 15 years studying at various universities—the London School of Economics, the University of Oxford, Harvard, and finally Yale Law School—picking up a string of degrees along the way. Today, I teach at Yale Law, where my students unnervingly resemble my younger self: They are, overwhelmingly, products of professional parents and high-class universities. I pass on to them the advantages that my own teachers bestowed on me. They, and I, owe our prosperity and our caste to meritocracy.

In the summer of 1987, I graduated from a public high school in Austin, Texas, and headed northeast to attend Yale. I then spent nearly 15 years studying at various universities—the London School of Economics, the University of Oxford, Harvard, and finally Yale Law School—picking up a string of degrees along the way. Today, I teach at Yale Law, where my students unnervingly resemble my younger self: They are, overwhelmingly, products of professional parents and high-class universities. I pass on to them the advantages that my own teachers bestowed on me. They, and I, owe our prosperity and our caste to meritocracy.

Two decades ago, when I started writing about economic inequality, meritocracy seemed more likely a cure than a cause. Meritocracy’s early advocates championed social mobility. In the 1960s, for instance, Yale President Kingman Brewster brought meritocratic admissions to the universitywith the express aim of breaking a hereditary elite. Alumni had long believed that their sons had a birthright to follow them to Yale; now prospective students would gain admission based on achievement rather than breeding. Meritocracy—for a time—replaced complacent insiders with talented and hardworking outsiders.

Today’s meritocrats still claim to get ahead through talent and effort, using means open to anyone. In practice, however, meritocracy now excludes everyone outside of a narrow elite.

More here.

Rather unintentionally, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers owns an enormous collection of fossils that would turn any paleontologist green with envy. “The U.S. Army Corps has collections that span the paleontological record,” says Nancy Brighton, a supervisory archaeologist for the Corps. “Basically anything related to animals and the natural world before humans came onto the scene.” The Corps never set out to amass this prehistoric tome. Rather, the fossils—from trilobites to dinosaurs, and everything in between—came as a kind of byproduct of the Corps’s actual, more logistical purpose: flood control (among other large-scale civil engineering projects).

Rather unintentionally, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers owns an enormous collection of fossils that would turn any paleontologist green with envy. “The U.S. Army Corps has collections that span the paleontological record,” says Nancy Brighton, a supervisory archaeologist for the Corps. “Basically anything related to animals and the natural world before humans came onto the scene.” The Corps never set out to amass this prehistoric tome. Rather, the fossils—from trilobites to dinosaurs, and everything in between—came as a kind of byproduct of the Corps’s actual, more logistical purpose: flood control (among other large-scale civil engineering projects). Lynskey’s background in musical criticism also leads to a highly original intervention in the ongoing debate over how authors influence one another. This has long been a contentious subject with respect to Orwell. Before composing 1984, Orwell claimed that Aldous Huxley’s classic satire warning of the dangers of hedonism and materialism, Brave New World (1932), essentially plagiarised Yevgeny Zamyatin’s We, a Soviet science fiction novel published in the 1920s. Critics later raised their eyebrows at how much Orwell’s own account of a conformist-mad land, which was published in 1949, owed to both of those earlier works.

Lynskey’s background in musical criticism also leads to a highly original intervention in the ongoing debate over how authors influence one another. This has long been a contentious subject with respect to Orwell. Before composing 1984, Orwell claimed that Aldous Huxley’s classic satire warning of the dangers of hedonism and materialism, Brave New World (1932), essentially plagiarised Yevgeny Zamyatin’s We, a Soviet science fiction novel published in the 1920s. Critics later raised their eyebrows at how much Orwell’s own account of a conformist-mad land, which was published in 1949, owed to both of those earlier works. Realism is back. After several decades of denying there was anything beyond interpretation, thinkers in the postmodern tradition are returning to reality. A new cluster of Continental thinkers—including Maurizio Ferraris, Graham Harman, and Markus Gabriel—argue that realism was unjustly, and unwisely, abandoned. While part of their motivation is purely philosophical, they also see realism as a defense against a crude, Nietzschean style of politics exemplified by a crop of world leaders who act as though the truth is whatever they say it is. Even in sociology, the thin, metaphysics-free theorizing of rational actor theory has been joined by “critical realism,” a metaphysically heavyweight view that accepts that things have objective natures that make them what they are, and powers that enable real causal interactions between things.

Realism is back. After several decades of denying there was anything beyond interpretation, thinkers in the postmodern tradition are returning to reality. A new cluster of Continental thinkers—including Maurizio Ferraris, Graham Harman, and Markus Gabriel—argue that realism was unjustly, and unwisely, abandoned. While part of their motivation is purely philosophical, they also see realism as a defense against a crude, Nietzschean style of politics exemplified by a crop of world leaders who act as though the truth is whatever they say it is. Even in sociology, the thin, metaphysics-free theorizing of rational actor theory has been joined by “critical realism,” a metaphysically heavyweight view that accepts that things have objective natures that make them what they are, and powers that enable real causal interactions between things. Ramallah, in the heart of the West Bank, is only a few miles north of Jerusalem, its nose pressed up against the dashes of Palestine’s borders on the maps, official markers of the city’s – and the country’s – provisional nature. It is a place of scarcely 30,000 inhabitants, historically a Christian city (although now the majority are Muslim) and also one of cold winters and carefully tended gardens, chosen by the PLO as its de facto headquarters following the Oslo accords of 1993 and 1995. It is, above all, a city of authors, home to Palestine’s greatest poet, the late

Ramallah, in the heart of the West Bank, is only a few miles north of Jerusalem, its nose pressed up against the dashes of Palestine’s borders on the maps, official markers of the city’s – and the country’s – provisional nature. It is a place of scarcely 30,000 inhabitants, historically a Christian city (although now the majority are Muslim) and also one of cold winters and carefully tended gardens, chosen by the PLO as its de facto headquarters following the Oslo accords of 1993 and 1995. It is, above all, a city of authors, home to Palestine’s greatest poet, the late  TSAKANE, South Africa — When she joined a trial of new tuberculosis drugs, the dying young woman weighed just 57 pounds. Stricken with a deadly strain of the disease, she was mortally terrified. Local nurses told her the Johannesburg hospital to which she must be transferred was very far away — and infested with vervet monkeys. “I cried the whole way in the ambulance,” Tsholofelo Msimango recalled recently. “They said I would live with monkeys and the sisters there were not nice and the food was bad and there was no way I would come back. They told my parents to fix the insurance because I would die.” Five years later, Ms. Msimango, 25, is now tuberculosis-free. She is healthy at 103 pounds, and has a young son. The trial she joined was small — it enrolled only 109 patients — but experts are calling the preliminary results groundbreaking. The drug regimen tested on Ms. Msimango has shown a 90 percent success rate against a deadly plague, extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis.

TSAKANE, South Africa — When she joined a trial of new tuberculosis drugs, the dying young woman weighed just 57 pounds. Stricken with a deadly strain of the disease, she was mortally terrified. Local nurses told her the Johannesburg hospital to which she must be transferred was very far away — and infested with vervet monkeys. “I cried the whole way in the ambulance,” Tsholofelo Msimango recalled recently. “They said I would live with monkeys and the sisters there were not nice and the food was bad and there was no way I would come back. They told my parents to fix the insurance because I would die.” Five years later, Ms. Msimango, 25, is now tuberculosis-free. She is healthy at 103 pounds, and has a young son. The trial she joined was small — it enrolled only 109 patients — but experts are calling the preliminary results groundbreaking. The drug regimen tested on Ms. Msimango has shown a 90 percent success rate against a deadly plague, extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis.

Adam Shatz in The New Yorker:

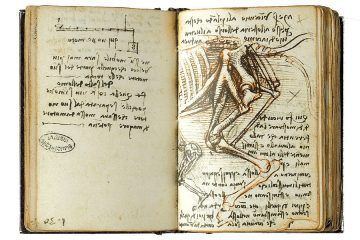

Adam Shatz in The New Yorker: As someone who appreciates Leonardo da Vinci’s painting skills, I’ve long marveled at how crowds rush past his most sublime painting, “The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne,” to line up in front of the “Mona Lisa” at the Louvre Museum in Paris. The art critic in me wants to say, “Wait! Look at this one. See the poses of entwining bodies and gazes, the melting regard of the mother for her child, the translucent folds of cloth, the baby’s chubby legs.” It’s a perfect combination of humanity and divinity. Now, at the 500th anniversary of Leonardo’s death, scholars, art lovers, and the public are taking a far-reaching look at his career. Exhibitions in Italy and England, as well as the largest-ever survey of his work that opens at the Louvre this fall, are celebrating the master’s achievements not only in art but also in science.

As someone who appreciates Leonardo da Vinci’s painting skills, I’ve long marveled at how crowds rush past his most sublime painting, “The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne,” to line up in front of the “Mona Lisa” at the Louvre Museum in Paris. The art critic in me wants to say, “Wait! Look at this one. See the poses of entwining bodies and gazes, the melting regard of the mother for her child, the translucent folds of cloth, the baby’s chubby legs.” It’s a perfect combination of humanity and divinity. Now, at the 500th anniversary of Leonardo’s death, scholars, art lovers, and the public are taking a far-reaching look at his career. Exhibitions in Italy and England, as well as the largest-ever survey of his work that opens at the Louvre this fall, are celebrating the master’s achievements not only in art but also in science. The roll of scientists born in the 19th century is as impressive as any century in history. Names such as Albert Einstein, Nikola Tesla, George Washington Carver, Alfred North Whitehead, Louis Agassiz, Benjamin Peirce, Leo Szilard, Edwin Hubble, Katharine Blodgett, Thomas Edison, Gerty Cori, Maria Mitchell, Annie Jump Cannon and Norbert Wiener created a legacy of knowledge and scientific method that fuels our modern lives. Which of these, though, was ‘the best’? Remarkably, in the brilliant light of these names, there was in fact a scientist who surpassed all others in sheer intellectual virtuosity. Charles Sanders Peirce (1839-1914), pronounced ‘purse’, was a solitary eccentric working in the town of Milford, Pennsylvania, isolated from any intellectual centre. Although many of his contemporaries shared the view that Peirce was a genius of historic proportions, he is little-known today. His current obscurity belies the prediction of the German mathematician Ernst Schröder, who said that Peirce’s ‘fame [will] shine like that of Leibniz or Aristotle into all the thousands of years to come’.

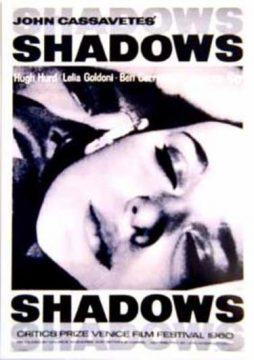

The roll of scientists born in the 19th century is as impressive as any century in history. Names such as Albert Einstein, Nikola Tesla, George Washington Carver, Alfred North Whitehead, Louis Agassiz, Benjamin Peirce, Leo Szilard, Edwin Hubble, Katharine Blodgett, Thomas Edison, Gerty Cori, Maria Mitchell, Annie Jump Cannon and Norbert Wiener created a legacy of knowledge and scientific method that fuels our modern lives. Which of these, though, was ‘the best’? Remarkably, in the brilliant light of these names, there was in fact a scientist who surpassed all others in sheer intellectual virtuosity. Charles Sanders Peirce (1839-1914), pronounced ‘purse’, was a solitary eccentric working in the town of Milford, Pennsylvania, isolated from any intellectual centre. Although many of his contemporaries shared the view that Peirce was a genius of historic proportions, he is little-known today. His current obscurity belies the prediction of the German mathematician Ernst Schröder, who said that Peirce’s ‘fame [will] shine like that of Leibniz or Aristotle into all the thousands of years to come’. Cassavetes felt galvanized by the looseness and freedom he (mis)read into jazz, which enabled him to make a film with little knowledge or money. At the very least, he shared one quality with Mingus — an ability to bully the people he worked with into doing what he wanted them to do. In a functional sense, both the radical filmmaker and the radical jazz composer were as domineering and rigid as the mainstream structures they railed against.

Cassavetes felt galvanized by the looseness and freedom he (mis)read into jazz, which enabled him to make a film with little knowledge or money. At the very least, he shared one quality with Mingus — an ability to bully the people he worked with into doing what he wanted them to do. In a functional sense, both the radical filmmaker and the radical jazz composer were as domineering and rigid as the mainstream structures they railed against. Each chapter explodes a common myth about language. Shariatmadari begins with the most common myth: that standards of English are declining. This is a centuries-old lament for which, he points out, there has never been any evidence. Older people buy into the myth because young people, who are more mobile and have wider social networks, are innovators in language as in other walks of life. Their habit of saying “aks” instead of “ask”, for instance, is a perfectly respectable example of metathesis, a natural linguistic process where the sounds in words swap round. (The word “wasp” used to be “waps” and “horse” used to be “hros”.) Youth is the driver of linguistic change. This means that older people feel linguistic alienation even as they control the institutions – universities, publishers, newspapers, broadcasters – that define standard English.

Each chapter explodes a common myth about language. Shariatmadari begins with the most common myth: that standards of English are declining. This is a centuries-old lament for which, he points out, there has never been any evidence. Older people buy into the myth because young people, who are more mobile and have wider social networks, are innovators in language as in other walks of life. Their habit of saying “aks” instead of “ask”, for instance, is a perfectly respectable example of metathesis, a natural linguistic process where the sounds in words swap round. (The word “wasp” used to be “waps” and “horse” used to be “hros”.) Youth is the driver of linguistic change. This means that older people feel linguistic alienation even as they control the institutions – universities, publishers, newspapers, broadcasters – that define standard English.