Ken Roth and Maya Wang in the New York Review of Books:

Classical totalitarianism, in which the state controls all institutions and most aspects of public life, largely died with the Soviet Union, apart from a few holdouts such as North Korea. The Chinese Communist Party retained a state monopoly in the political realm but allowed a significant private economy to flourish. Yet today, in Xinjiang, a region in China’s northwest, a new totalitarianism is emerging—one built not on state ownership of enterprises or property but on the state’s intrusive collection and analysis of information about the people there. Xinjiang shows us what a surveillance state looks like under a government that brooks no dissent and seeks to preclude the ability to fight back. And it demonstrates the power of personal information as a tool of social control.

Xinjiang covers 16 percent of China’s landmass but includes only a tiny fraction of its population—22 million people, roughly 13 million of whom are Uighur and other Turkic Muslims, out of nearly 1.4 billion people in China. Hardly lax about security anywhere in the country, the Chinese government is especially preoccupied with it in Xinjiang, justifying the resulting repression as a fight against the “Three Evils” of “separatism, terrorism, and extremism.”

Yet far from targeting bona fide criminals, Beijing’s actions in Xinjiang have been extraordinarily indiscriminate. As is now generally known, Chinese authorities have detained one million or more Turkic Muslims for political “re-education.”

More here.

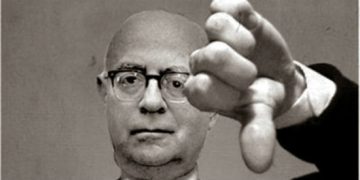

Academic, stuffy, German – Theodor W. Adorno has become emblematic of a certain sense of unfeeling in art. He was critical of TV, partial to Schoenberg, and aggrieved by the crassness of life in exile in 1940s America. Some of his students, infatuated with the youthful spontaneity of 1968, supposed that Adorno represented the old institutions that continued into post-war Europe, seeing his criticisms of mass culture being ‘pre-digested’ as identical to the conservative dismissal of contemporary art, culture, and even values. Determined to take action, they scrawled ‘If Adorno is left in peace, capitalism will never cease’ on the blackboard. Three of them surrounded him and exposed their breasts as others handed out leaflets proclaiming, ‘Adorno as an institution is dead.’ Adorno would confide in Max Horkheimer, writing: ‘To have picked me of all people, I who have always spoken out against every type of erotic repression and sexual taboo!’

Academic, stuffy, German – Theodor W. Adorno has become emblematic of a certain sense of unfeeling in art. He was critical of TV, partial to Schoenberg, and aggrieved by the crassness of life in exile in 1940s America. Some of his students, infatuated with the youthful spontaneity of 1968, supposed that Adorno represented the old institutions that continued into post-war Europe, seeing his criticisms of mass culture being ‘pre-digested’ as identical to the conservative dismissal of contemporary art, culture, and even values. Determined to take action, they scrawled ‘If Adorno is left in peace, capitalism will never cease’ on the blackboard. Three of them surrounded him and exposed their breasts as others handed out leaflets proclaiming, ‘Adorno as an institution is dead.’ Adorno would confide in Max Horkheimer, writing: ‘To have picked me of all people, I who have always spoken out against every type of erotic repression and sexual taboo!’ And yet the issues on which Boas and Mead made their interventions, issues around race and gender, are now at the center of public life, and they bring all the nature-nurture confusion back with them. The focus of the conversation today is identity, and identity seems to be a concept that lies beyond both culture and biology. Is identity innate, or is it socially constructed? Is it fated, or can it be chosen or performed? Are our identities defined by the existing state of social relations, or do we carry them with us wherever we go?

And yet the issues on which Boas and Mead made their interventions, issues around race and gender, are now at the center of public life, and they bring all the nature-nurture confusion back with them. The focus of the conversation today is identity, and identity seems to be a concept that lies beyond both culture and biology. Is identity innate, or is it socially constructed? Is it fated, or can it be chosen or performed? Are our identities defined by the existing state of social relations, or do we carry them with us wherever we go? A

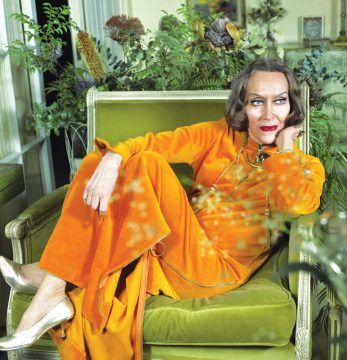

A One evening in early 1950, the film mogul Louis B. Mayer hosted a small dinner party for the actress Gloria Swanson. She was fifty-one years old, which was not considered an ancient, crone-like age, even in an industry that values youth above all else. Still, she was in need of a professional boost. Mayer’s small soiree was something of a ceremonial gesture. Here was one of the last tycoons of classic Hollywood extending his hand and his hospitality to an actress who was tottering, on marabou-covered heels, back into the business after a decade-long fermata.

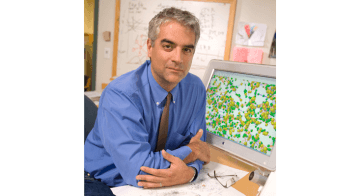

One evening in early 1950, the film mogul Louis B. Mayer hosted a small dinner party for the actress Gloria Swanson. She was fifty-one years old, which was not considered an ancient, crone-like age, even in an industry that values youth above all else. Still, she was in need of a professional boost. Mayer’s small soiree was something of a ceremonial gesture. Here was one of the last tycoons of classic Hollywood extending his hand and his hospitality to an actress who was tottering, on marabou-covered heels, back into the business after a decade-long fermata. Nicholas Christakis and I are on the same page: We would definitely sacrifice our lives to save a billion strangers, perhaps even several hundred million, plucked at random from Earth’s population. But, for sure, not a thousand strangers, or a million. Those numbers seem, somehow, too insignificant. Christakis, the director of the Human Nature Lab at Yale University, shared this

Nicholas Christakis and I are on the same page: We would definitely sacrifice our lives to save a billion strangers, perhaps even several hundred million, plucked at random from Earth’s population. But, for sure, not a thousand strangers, or a million. Those numbers seem, somehow, too insignificant. Christakis, the director of the Human Nature Lab at Yale University, shared this  John Rawls

John Rawls Memory takes different forms. Memories can be encoded in the strength of neural connections in our brains, but there’s a sense in which photographs and written records are memories as well. What did people do before such forms of memory even existed? Lynne Kelly is a science writer and researcher who specializes in forms of memory in the ancient world, as well as a competitive memory expert in her own right. She has theorized that ancient structures such as Stonehenge might have served as memory palaces, encoding social knowledge over extended periods of time. We talk about how to improve your own memory, the origin of religion, and how prehistoric cultures preserved their know-how.

Memory takes different forms. Memories can be encoded in the strength of neural connections in our brains, but there’s a sense in which photographs and written records are memories as well. What did people do before such forms of memory even existed? Lynne Kelly is a science writer and researcher who specializes in forms of memory in the ancient world, as well as a competitive memory expert in her own right. She has theorized that ancient structures such as Stonehenge might have served as memory palaces, encoding social knowledge over extended periods of time. We talk about how to improve your own memory, the origin of religion, and how prehistoric cultures preserved their know-how. The climate crisis is an issue that requires long-term thinking across the generations, yet electoral politics is geared toward responding to immediate grievances. Politicians can talk about taking the long view, but without institutional changes to the way we practice democracy, they are unlikely to look beyond short-term political gains.

The climate crisis is an issue that requires long-term thinking across the generations, yet electoral politics is geared toward responding to immediate grievances. Politicians can talk about taking the long view, but without institutional changes to the way we practice democracy, they are unlikely to look beyond short-term political gains. Few political poems strike emotional pay dirt with such consistency and effect as ‘September 1, 1939’. In the sprung rhythm of his three-beat line, with each of his eleven-line stanzas containing one sentence, the language leaps at our hearts and minds. Auden’s infamous cleverness and his wide allusiveness continue after many readings to startle in satisfying ways, even when we don’t recall exactly ‘what occurred at Linz’ or really know ‘What huge imago made/A psychopathic god’. What follows, of course, from these puzzling lines is the poem’s most clarifying moment: ‘I and the public know/What all schoolchildren learn,/Those to

Few political poems strike emotional pay dirt with such consistency and effect as ‘September 1, 1939’. In the sprung rhythm of his three-beat line, with each of his eleven-line stanzas containing one sentence, the language leaps at our hearts and minds. Auden’s infamous cleverness and his wide allusiveness continue after many readings to startle in satisfying ways, even when we don’t recall exactly ‘what occurred at Linz’ or really know ‘What huge imago made/A psychopathic god’. What follows, of course, from these puzzling lines is the poem’s most clarifying moment: ‘I and the public know/What all schoolchildren learn,/Those to  Around October 20, 1969, Sanders received a copy of an ecology newsletter called Earth Read-Out in the mail. The newsletter reprinted a five-day-old San Francisco Chronicle story describing two police raids on a remote desert ranch in California: “A band of nude and long-haired thieves who ranged over Death Valley in stolen dune buggies” had been rounded up. Sanders read the story with some interest, then put it aside. Six weeks later, when Manson’s picture was plastered across the front pages of newspapers, along with reports of the horrific crimes he’d allegedly orchestrated, Sanders recalled the thieves in the desert.

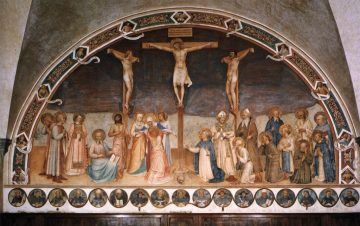

Around October 20, 1969, Sanders received a copy of an ecology newsletter called Earth Read-Out in the mail. The newsletter reprinted a five-day-old San Francisco Chronicle story describing two police raids on a remote desert ranch in California: “A band of nude and long-haired thieves who ranged over Death Valley in stolen dune buggies” had been rounded up. Sanders read the story with some interest, then put it aside. Six weeks later, when Manson’s picture was plastered across the front pages of newspapers, along with reports of the horrific crimes he’d allegedly orchestrated, Sanders recalled the thieves in the desert. In the summer of 1873, Henry James visited a former monastery on Piazza San Marco in Florence. Surrounded by a scattering of low-slung, washed-out government buildings and conical Tuscan cypresses, the church and convent were in what is still the city’s center. When James first entered the convent, he saw Fra Angelico’s The Crucifixion with Saints in the chapter room. A brightly colored, semicircle fresco about thirty feet wide, Crucifixion depicts Christ and the two thieves on either side of him, nailed to their crosses, as saints and witnesses grieve below. “I looked long,” James wrote. “One can hardly do otherwise.” As the author moved throughout what had then just become a museum, he felt a spiritual urge, even though he had rejected his Christian upbringing. “You may be as little of a formal Christian as Fra Angelico was much of one,” he wrote in Italian Hours. “You yet feel admonished by spiritual decency to let so yearning a view of the Christian story work its utmost will on you.” Even Angelico’s colors, he added, seem divinely infinite, “dissolved in tears that drop and drop, however softly, through all time.”

In the summer of 1873, Henry James visited a former monastery on Piazza San Marco in Florence. Surrounded by a scattering of low-slung, washed-out government buildings and conical Tuscan cypresses, the church and convent were in what is still the city’s center. When James first entered the convent, he saw Fra Angelico’s The Crucifixion with Saints in the chapter room. A brightly colored, semicircle fresco about thirty feet wide, Crucifixion depicts Christ and the two thieves on either side of him, nailed to their crosses, as saints and witnesses grieve below. “I looked long,” James wrote. “One can hardly do otherwise.” As the author moved throughout what had then just become a museum, he felt a spiritual urge, even though he had rejected his Christian upbringing. “You may be as little of a formal Christian as Fra Angelico was much of one,” he wrote in Italian Hours. “You yet feel admonished by spiritual decency to let so yearning a view of the Christian story work its utmost will on you.” Even Angelico’s colors, he added, seem divinely infinite, “dissolved in tears that drop and drop, however softly, through all time.” Jay Shetty is 8 years old. He is smart and bright, says his mother Shilpa, even if he can’t do all the things his younger brother can. “Jay doesn’t sit up or use his hands much. He’s non-verbal and we don’t know how well he can see,” she says. “But he plays with us and tries to copy everything his younger brother Kairav does.”

Jay Shetty is 8 years old. He is smart and bright, says his mother Shilpa, even if he can’t do all the things his younger brother can. “Jay doesn’t sit up or use his hands much. He’s non-verbal and we don’t know how well he can see,” she says. “But he plays with us and tries to copy everything his younger brother Kairav does.” One day, doctors may be able to use the metabolites in blood samples to predict the likelihood of a person surviving another five to 10 years, according to a newly developed tool described today (August 20) in

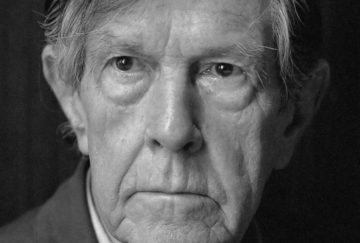

One day, doctors may be able to use the metabolites in blood samples to predict the likelihood of a person surviving another five to 10 years, according to a newly developed tool described today (August 20) in  Milton Babbitt and John Cage, two of the most notorious postwar American composers, are often thought to be antipodal figures. Babbitt is straight, Jewish, politically conservative, and southern, a skeptical rationalist who talks like a mathematician on speed. Cage–who died in 1992–was gay, goyish, politically left, and Californian, a genial fruitcake whose enthusiasms ran toward astrology, mushrooms, Zen, and anarchist politics. Babbitt’s music is fastidiously organized, each of his notes carefully placed within multiple nested rhythmic and melodic patterns. Cage’s music, by contrast, is scrupulously disorganized, composed randomly–for instance by tossing coins or tracing astronomical maps onto music paper. Not surprisingly, Babbitt is an academic, and has many students who teach at music departments throughout the country. Cage, who never graduated from college, was an auto-didact (more or less), and has had at least as much influence on visual arts and popular music as on the world of academic musical composition.

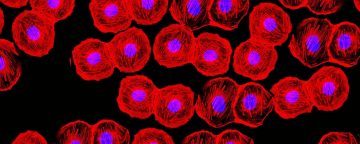

Milton Babbitt and John Cage, two of the most notorious postwar American composers, are often thought to be antipodal figures. Babbitt is straight, Jewish, politically conservative, and southern, a skeptical rationalist who talks like a mathematician on speed. Cage–who died in 1992–was gay, goyish, politically left, and Californian, a genial fruitcake whose enthusiasms ran toward astrology, mushrooms, Zen, and anarchist politics. Babbitt’s music is fastidiously organized, each of his notes carefully placed within multiple nested rhythmic and melodic patterns. Cage’s music, by contrast, is scrupulously disorganized, composed randomly–for instance by tossing coins or tracing astronomical maps onto music paper. Not surprisingly, Babbitt is an academic, and has many students who teach at music departments throughout the country. Cage, who never graduated from college, was an auto-didact (more or less), and has had at least as much influence on visual arts and popular music as on the world of academic musical composition. Aggressive cancers can spread so fiercely that they seem less like tissues gone wrong and more like invasive parasites looking to consume and then break free of their host. If a wild theory

Aggressive cancers can spread so fiercely that they seem less like tissues gone wrong and more like invasive parasites looking to consume and then break free of their host. If a wild theory