Daniel Markovits in The Atlantic:

Two decades ago, when I started writing about economic inequality, meritocracy seemed more likely a cure than a cause. Meritocracy’s early advocates championed social mobility. In the 1960s, for instance, Yale President Kingman Brewster brought meritocratic admissions to the universitywith the express aim of breaking a hereditary elite. Alumni had long believed that their sons had a birthright to follow them to Yale; now prospective students would gain admission based on achievement rather than breeding. Meritocracy—for a time—replaced complacent insiders with talented and hardworking outsiders.Today’s meritocrats still claim to get ahead through talent and effort, using means open to anyone. In practice, however, meritocracy now excludes everyone outside of a narrow elite. Harvard, Princeton, Stanford, and Yale collectively enroll more students from households in the top 1 percent of the income distribution than from households in the bottom 60 percent. Legacy preferences, nepotism, and outright fraud continue to give rich applicants corrupt advantages. But the dominant causes of this skew toward wealth can be traced to meritocracy. On average, children whose parents make more than $200,000 a year score about 250 points higher on the SAT than children whose parents make $40,000 to $60,000. Only about one in 200 children from the poorest third of households achieves SAT scores at Yale’s median. Meanwhile, the top banks and law firms, along with other high-paying employers, recruit almost exclusively from a few elite colleges.

Two decades ago, when I started writing about economic inequality, meritocracy seemed more likely a cure than a cause. Meritocracy’s early advocates championed social mobility. In the 1960s, for instance, Yale President Kingman Brewster brought meritocratic admissions to the universitywith the express aim of breaking a hereditary elite. Alumni had long believed that their sons had a birthright to follow them to Yale; now prospective students would gain admission based on achievement rather than breeding. Meritocracy—for a time—replaced complacent insiders with talented and hardworking outsiders.Today’s meritocrats still claim to get ahead through talent and effort, using means open to anyone. In practice, however, meritocracy now excludes everyone outside of a narrow elite. Harvard, Princeton, Stanford, and Yale collectively enroll more students from households in the top 1 percent of the income distribution than from households in the bottom 60 percent. Legacy preferences, nepotism, and outright fraud continue to give rich applicants corrupt advantages. But the dominant causes of this skew toward wealth can be traced to meritocracy. On average, children whose parents make more than $200,000 a year score about 250 points higher on the SAT than children whose parents make $40,000 to $60,000. Only about one in 200 children from the poorest third of households achieves SAT scores at Yale’s median. Meanwhile, the top banks and law firms, along with other high-paying employers, recruit almost exclusively from a few elite colleges.

Hardworking outsiders no longer enjoy genuine opportunity. According to one study, only one out of every 100 children born into the poorest fifth of households, and fewer than one out of every 50 children born into the middle fifth, will join the top 5 percent. Absolute economic mobility is also declining—the odds that a middle-class child will outearn his parents have fallen by more than half since mid-century—and the drop is greater among the middle class than among the poor. Meritocracy frames this exclusion as a failure to measure up, adding a moral insult to economic injury.

More here.

In the booklet’s foreword, the Very Reverend W. R. Matthews, then the Dean of St. Paul’s, claimed that “the devastation of war has given us an opportunity which will never come again.” This optimism echoed sentiments expressed during the war itself. The country would turn bombsites into social housing and hospitals, with a few churches left as memorials to the carnage of the home front. (As Brian Foss has pointed out, it wasn’t until September 1941 that frontline casualties outnumbered civilian deaths in Britain.) The short booklet is full of halftone illustrations, architectural plans, and garden plans, showing how to transform destroyed buildings into “ruins.” In one article, Hugh Casson argued that “every stone—whether fallen or in place—is a fragment of the past, part of the pattern of history.” Churches such as St. Dunstan and Christ Church, Newgate Street, scarred by the Great Fire of London and the Blitz, are now living monuments not just to the bombs and fires, but to London’s long history of transformation. Casson worried about a time when “all traces of war damage will have gone, and its strange beauty vanished from our streets…and with their going the ordeal through which we passed will seem remote, unreal, perhaps forgotten.”

In the booklet’s foreword, the Very Reverend W. R. Matthews, then the Dean of St. Paul’s, claimed that “the devastation of war has given us an opportunity which will never come again.” This optimism echoed sentiments expressed during the war itself. The country would turn bombsites into social housing and hospitals, with a few churches left as memorials to the carnage of the home front. (As Brian Foss has pointed out, it wasn’t until September 1941 that frontline casualties outnumbered civilian deaths in Britain.) The short booklet is full of halftone illustrations, architectural plans, and garden plans, showing how to transform destroyed buildings into “ruins.” In one article, Hugh Casson argued that “every stone—whether fallen or in place—is a fragment of the past, part of the pattern of history.” Churches such as St. Dunstan and Christ Church, Newgate Street, scarred by the Great Fire of London and the Blitz, are now living monuments not just to the bombs and fires, but to London’s long history of transformation. Casson worried about a time when “all traces of war damage will have gone, and its strange beauty vanished from our streets…and with their going the ordeal through which we passed will seem remote, unreal, perhaps forgotten.” L

L The difficulty of Hammons’s work is that it seems to preempt any possible critical response and offer up an implicit rebuttal. This was most evident in the centerpiece of the show, a grid of tents pitched in the gallery’s interior courtyard, which is located between the entrance to the gallery’s chic, industrial compound and the exhibition spaces. Each tent bore a stenciled threat: this could be u. My first reaction was dismissive; the installation seemed too obvious, too lazily reliant on a contextual friction that was intended to point to a larger one, since the gallery—a sign of advanced gentrification if ever there was one—sits just a few blocks from the homeless encampments of Skid Row. OK, we’re all complicit: now what?

The difficulty of Hammons’s work is that it seems to preempt any possible critical response and offer up an implicit rebuttal. This was most evident in the centerpiece of the show, a grid of tents pitched in the gallery’s interior courtyard, which is located between the entrance to the gallery’s chic, industrial compound and the exhibition spaces. Each tent bore a stenciled threat: this could be u. My first reaction was dismissive; the installation seemed too obvious, too lazily reliant on a contextual friction that was intended to point to a larger one, since the gallery—a sign of advanced gentrification if ever there was one—sits just a few blocks from the homeless encampments of Skid Row. OK, we’re all complicit: now what? THE CATO INSTITUTE,

THE CATO INSTITUTE, Loss is a cousin of loneliness. They intersect and overlap, and so it’s not surprising that a work of mourning might invoke a feeling of aloneness, of separation. Mortality is lonely. Physical existence is lonely by its nature, stuck in a body that’s moving inexorably towards decay, shrinking, wastage and fracture. Then there’s the loneliness of bereavement, the loneliness of lost or damaged love, of missing one or many specific people, the loneliness of mourning.

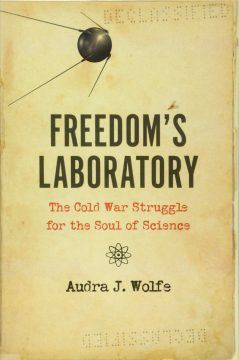

Loss is a cousin of loneliness. They intersect and overlap, and so it’s not surprising that a work of mourning might invoke a feeling of aloneness, of separation. Mortality is lonely. Physical existence is lonely by its nature, stuck in a body that’s moving inexorably towards decay, shrinking, wastage and fracture. Then there’s the loneliness of bereavement, the loneliness of lost or damaged love, of missing one or many specific people, the loneliness of mourning. The word “science” typically evokes epistemic ambitions to explore the fundamental laws of the natural world. This is the stuff of philosophical reflection and documentary specials—and it is unquestionably important. This ethereal vision of science appears starkly divorced from the messy fray of “politics,” however you might want to understand the term.

The word “science” typically evokes epistemic ambitions to explore the fundamental laws of the natural world. This is the stuff of philosophical reflection and documentary specials—and it is unquestionably important. This ethereal vision of science appears starkly divorced from the messy fray of “politics,” however you might want to understand the term. In 1915, Albert Einstein wrote a letter to the philosopher and physicist Moritz Schlick, who had recently composed an article on the theory of relativity. Einstein praised it: ‘From the philosophical perspective, nothing nearly as clear seems to have been written on the topic.’ Then he went on to express his intellectual debt to ‘Hume, whose Treatise of Human Nature I had studied avidly and with admiration shortly before discovering the theory of relativity. It is very possible that without these philosophical studies I would not have arrived at the solution.’

In 1915, Albert Einstein wrote a letter to the philosopher and physicist Moritz Schlick, who had recently composed an article on the theory of relativity. Einstein praised it: ‘From the philosophical perspective, nothing nearly as clear seems to have been written on the topic.’ Then he went on to express his intellectual debt to ‘Hume, whose Treatise of Human Nature I had studied avidly and with admiration shortly before discovering the theory of relativity. It is very possible that without these philosophical studies I would not have arrived at the solution.’ Women in loose robes dragged toddlers, babies propped upon their hips. Men carrying parents and grandparents on their shoulders stepped ahead, calling back for assurances as women collapsed in the heat. Flimsy plastic bags, crammed with clothes and other belongings, dangled off shoulders and wrists. In the midday glaze, as light shimmered off the desert like water droplets, the scene at the Syrian-Iraqi border seemed almost biblical. My Iraqi colleague Ali, who had already tasted the wrath of displacement from his own country, squatted in the shade of our car and cried.

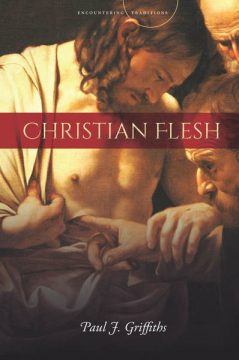

Women in loose robes dragged toddlers, babies propped upon their hips. Men carrying parents and grandparents on their shoulders stepped ahead, calling back for assurances as women collapsed in the heat. Flimsy plastic bags, crammed with clothes and other belongings, dangled off shoulders and wrists. In the midday glaze, as light shimmered off the desert like water droplets, the scene at the Syrian-Iraqi border seemed almost biblical. My Iraqi colleague Ali, who had already tasted the wrath of displacement from his own country, squatted in the shade of our car and cried. To put it mildly, Christianity has a complicated relationship with flesh. The same Paul who declared the Lord’s ownership of the body also bequeathed to subsequent Christian history a disdain for physicality through his—misunderstood, as most interpreters now think, but no less influential for being so—sharp contrast between the life of the flesh and the new life bestowed by and in the Spirit of Jesus. Stark affirmations such as the one he wrote to the Corinthians—“flesh and blood cannot inherit the kingdom of God”—at minimum lent confidence to later Christian denigrators of the body who imagined salvation as an escape from fleshly imprisonment and, at maximum, convinced generations of Christians that following Jesus ought to entail hating the body.

To put it mildly, Christianity has a complicated relationship with flesh. The same Paul who declared the Lord’s ownership of the body also bequeathed to subsequent Christian history a disdain for physicality through his—misunderstood, as most interpreters now think, but no less influential for being so—sharp contrast between the life of the flesh and the new life bestowed by and in the Spirit of Jesus. Stark affirmations such as the one he wrote to the Corinthians—“flesh and blood cannot inherit the kingdom of God”—at minimum lent confidence to later Christian denigrators of the body who imagined salvation as an escape from fleshly imprisonment and, at maximum, convinced generations of Christians that following Jesus ought to entail hating the body. For a brief moment,

For a brief moment,  The eminent art historian Michael Fried has set out, in his own energetic and independent style, to answer this question—what was literary impressionism?—and to do so unencumbered by the general principles that have so far cohered around the term in the work of literary critics and art historians. This may bother some readers who expect a more direct engagement with the critical history of the term. Fried’s approach is to start the inquiry afresh, using detailed readings of passages in individual works to derive his own answer to his title’s question. “If my specific readings and my overall argument cumulatively gain traction on their own terms,” he writes, “I shall consider this book a success.”

The eminent art historian Michael Fried has set out, in his own energetic and independent style, to answer this question—what was literary impressionism?—and to do so unencumbered by the general principles that have so far cohered around the term in the work of literary critics and art historians. This may bother some readers who expect a more direct engagement with the critical history of the term. Fried’s approach is to start the inquiry afresh, using detailed readings of passages in individual works to derive his own answer to his title’s question. “If my specific readings and my overall argument cumulatively gain traction on their own terms,” he writes, “I shall consider this book a success.” It consists of nothing more than an intermittent correspondence between two friends. Yet the epistolary form is deceptively efficient, supplying backstory, plot, character, dialogue and more than one narrative voice before a conventional novel might have cleared its throat. Within a page or two, we are in the world of Martin and Max, both German, the latter a Jew now living in San Francisco, the former now back in Munich – two men who have been business partners, friends and whose families have, as we shall discover, been intimately connected.

It consists of nothing more than an intermittent correspondence between two friends. Yet the epistolary form is deceptively efficient, supplying backstory, plot, character, dialogue and more than one narrative voice before a conventional novel might have cleared its throat. Within a page or two, we are in the world of Martin and Max, both German, the latter a Jew now living in San Francisco, the former now back in Munich – two men who have been business partners, friends and whose families have, as we shall discover, been intimately connected. Is there anything CRISPR can’t do? Scientists have wielded

Is there anything CRISPR can’t do? Scientists have wielded  A living room in Grantwood, N.J., has a good claim to being the birthplace, in the late 1920s and early 1930s, of a new science of humankind. Amid the demands of advising and fund-raising, the chair of the Columbia University anthropology department, Franz Boas, had decided to host regular Tuesday evening seminars at his suburban home. His students, passing plates of oatmeal cookies, were elaborating a way of seeing the world. They called it cultural relativity. Their essential finding was that societies did not come rank-ordered as civilized or primitive, moral or deviant. Each culture was only a sampling taken from the vast inventory of possible human beliefs and practices.

A living room in Grantwood, N.J., has a good claim to being the birthplace, in the late 1920s and early 1930s, of a new science of humankind. Amid the demands of advising and fund-raising, the chair of the Columbia University anthropology department, Franz Boas, had decided to host regular Tuesday evening seminars at his suburban home. His students, passing plates of oatmeal cookies, were elaborating a way of seeing the world. They called it cultural relativity. Their essential finding was that societies did not come rank-ordered as civilized or primitive, moral or deviant. Each culture was only a sampling taken from the vast inventory of possible human beliefs and practices. Just about everything we know that decreases the risk of developing cancer — exercise, healthful eating, not smoking, and the like — is associated with healthier tissues, which favor normal cell types.

Just about everything we know that decreases the risk of developing cancer — exercise, healthful eating, not smoking, and the like — is associated with healthier tissues, which favor normal cell types.