Lidija Haas at Bookforum:

TAKE A MINUTE NOW to write down the first associations that come to your mind regarding Clarence Thomas. You might note that he represents the extreme right wing of the Supreme Court and that, beginning his twenty-ninth term this fall, he is its longest-serving justice, not to mention Donald Trump’s personal favorite. No doubt you’ll think of his alleged sexual harassment of Anita Hill during his tenure at the Department of Education and when he was head of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission under Ronald Reagan, of the ordeal she went through when forced to testify about it during his 1991 confirmation hearings, to no avail, and of his own infamous characterization of those hearings as a “high-tech lynching.” Perhaps his conspicuous quiet will come to mind, his refusal to say anything during oral arguments for years at a time—the New York Times reported somewhat breathlessly in 2016 that Thomas had just resumed speaking from the bench after keeping shtum for an entire decade. You may also recall the flurry of news coverage that ensued recently when, not content simply to go along with the majority opinion in Box v. Planned Parenthood of Indiana and Kentucky, which upheld Indiana’s right to require that aborted fetuses receive funerary rites, he added a long and fervent concurring opinion that connected abortion rights to eugenics and the US’s ugly history of forced sterilization. I’m guessing, though, that you probably wouldn’t start by describing Thomas as, in Corey Robin’s words, “a conservative black nationalist on the Supreme Court.”

TAKE A MINUTE NOW to write down the first associations that come to your mind regarding Clarence Thomas. You might note that he represents the extreme right wing of the Supreme Court and that, beginning his twenty-ninth term this fall, he is its longest-serving justice, not to mention Donald Trump’s personal favorite. No doubt you’ll think of his alleged sexual harassment of Anita Hill during his tenure at the Department of Education and when he was head of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission under Ronald Reagan, of the ordeal she went through when forced to testify about it during his 1991 confirmation hearings, to no avail, and of his own infamous characterization of those hearings as a “high-tech lynching.” Perhaps his conspicuous quiet will come to mind, his refusal to say anything during oral arguments for years at a time—the New York Times reported somewhat breathlessly in 2016 that Thomas had just resumed speaking from the bench after keeping shtum for an entire decade. You may also recall the flurry of news coverage that ensued recently when, not content simply to go along with the majority opinion in Box v. Planned Parenthood of Indiana and Kentucky, which upheld Indiana’s right to require that aborted fetuses receive funerary rites, he added a long and fervent concurring opinion that connected abortion rights to eugenics and the US’s ugly history of forced sterilization. I’m guessing, though, that you probably wouldn’t start by describing Thomas as, in Corey Robin’s words, “a conservative black nationalist on the Supreme Court.”

more here.

O

O Coates doesn’t linger on the gruesome realities of slavery. There are no extended scenes of abuse. His novel increasingly begins to bend toward the motifs and impulses of the comic book and superhero world. “A power was within me,” Hiram says, “but with no thought of how to access it or control it, I was lost.” He seeks a mentor. She is called Moses. Others know her by the name Harriet Tubman, who in this novel is not merely the abolitionist who made daring missions to rescue enslaved people but a woman known to some as “the living master of Conduction.”

Coates doesn’t linger on the gruesome realities of slavery. There are no extended scenes of abuse. His novel increasingly begins to bend toward the motifs and impulses of the comic book and superhero world. “A power was within me,” Hiram says, “but with no thought of how to access it or control it, I was lost.” He seeks a mentor. She is called Moses. Others know her by the name Harriet Tubman, who in this novel is not merely the abolitionist who made daring missions to rescue enslaved people but a woman known to some as “the living master of Conduction.” This is the tale of a man who fled from desperate confinement, whirled into Polynesian dreamlands on a plank, sailed back to “civilization,” and then, his genius predictably unremunerated, had to tour the universe in a little room. His biographer calls him “an unfortunate fellow who had come to maturity penniless and poorly educated.” Unfortunate was likewise how he ended. Who could have predicted the greatness that lay before Herman Melville? In 1841, the earnest young man sneaked out on his unpaid landlady and signed on with the New Bedford whaler Acushnet, bound for the South Seas. He was 21, eager and shockingly open-minded, yearning not just to see but to live. In

This is the tale of a man who fled from desperate confinement, whirled into Polynesian dreamlands on a plank, sailed back to “civilization,” and then, his genius predictably unremunerated, had to tour the universe in a little room. His biographer calls him “an unfortunate fellow who had come to maturity penniless and poorly educated.” Unfortunate was likewise how he ended. Who could have predicted the greatness that lay before Herman Melville? In 1841, the earnest young man sneaked out on his unpaid landlady and signed on with the New Bedford whaler Acushnet, bound for the South Seas. He was 21, eager and shockingly open-minded, yearning not just to see but to live. In  Piano players’ brains look different from those of violin players. Researchers have shown changes in brain activity in response to a short-term intervention in which girls played Tetris regularly — their visual-spatial brain areas seemed to enlarge. Such evidence of brain plasticity is key to Gina Rippon’s new book, “Gender and Our Brains” (which, yes, does relate the story of Phineas Gage, as well as that of the dead fish). The book is, at the core, concerned with the question of whether male and female brains are different. Rippon, a British professor of cognitive neuroimaging, reviews the history of studies of the gendered brain. The most persistent feature of these studies is the focus on size. Men have bigger brains on average, going along with their generally larger bodies, a fact that has come up again and again as an argument for male superiority, or at least structural difference. Size has fallen out of fashion, but the desire to identify gender-specific parts of the brain has not.

Piano players’ brains look different from those of violin players. Researchers have shown changes in brain activity in response to a short-term intervention in which girls played Tetris regularly — their visual-spatial brain areas seemed to enlarge. Such evidence of brain plasticity is key to Gina Rippon’s new book, “Gender and Our Brains” (which, yes, does relate the story of Phineas Gage, as well as that of the dead fish). The book is, at the core, concerned with the question of whether male and female brains are different. Rippon, a British professor of cognitive neuroimaging, reviews the history of studies of the gendered brain. The most persistent feature of these studies is the focus on size. Men have bigger brains on average, going along with their generally larger bodies, a fact that has come up again and again as an argument for male superiority, or at least structural difference. Size has fallen out of fashion, but the desire to identify gender-specific parts of the brain has not. Democracy, like fitness, has a point. No matter what one might believe about democracy’s intrinsic value, what makes it such an important social good is that it enables goods of other kinds to flourish. When these other goods are crowded out of our collective lives, democracy becomes pathological.

Democracy, like fitness, has a point. No matter what one might believe about democracy’s intrinsic value, what makes it such an important social good is that it enables goods of other kinds to flourish. When these other goods are crowded out of our collective lives, democracy becomes pathological.

A Hungarian writer, known worldwide; a political thinker who greatly influenced the intellectual life of the last fin de siècle; the third member of the great Central European triad, together with Milan Kundera and Danilo Kiš; one of the intellectual leaders of the democratic transformation of Hungary. György Konrád is gone.

A Hungarian writer, known worldwide; a political thinker who greatly influenced the intellectual life of the last fin de siècle; the third member of the great Central European triad, together with Milan Kundera and Danilo Kiš; one of the intellectual leaders of the democratic transformation of Hungary. György Konrád is gone. “[F]ungi are the grand recyclers of our planet,” writes mycologist Paul Stamets in Mycelium Running, “the mycomagicians disassembling large organic molecules into simpler forms, which in turn nourish other members of the ecological community.” Certain fungi, known as saprophytes (from the Greek sapro: “rotten” and phytes: “plants”), feed upon decaying or dead organic matter. These industrious mushrooms—portobello, cremini, oyster, reishi, enoki, royal trumpets, shiitake, white button—speed up decomposition, restore and aerate soil, and provide food for other life forms, from bacteria to bears. “The yeasts and molds used in making beer, wine, cheese, and bread are all saprophytes,” notes journalist and food writer Eugenia Bone in Mycophilia. So rot-eating fungi helped civilize us, Bone notes, “if you consider good wine an indicator of civilization.”

“[F]ungi are the grand recyclers of our planet,” writes mycologist Paul Stamets in Mycelium Running, “the mycomagicians disassembling large organic molecules into simpler forms, which in turn nourish other members of the ecological community.” Certain fungi, known as saprophytes (from the Greek sapro: “rotten” and phytes: “plants”), feed upon decaying or dead organic matter. These industrious mushrooms—portobello, cremini, oyster, reishi, enoki, royal trumpets, shiitake, white button—speed up decomposition, restore and aerate soil, and provide food for other life forms, from bacteria to bears. “The yeasts and molds used in making beer, wine, cheese, and bread are all saprophytes,” notes journalist and food writer Eugenia Bone in Mycophilia. So rot-eating fungi helped civilize us, Bone notes, “if you consider good wine an indicator of civilization.” Among the memorable stories in Benjamin Moser’s engrossing, unsettling biography of

Among the memorable stories in Benjamin Moser’s engrossing, unsettling biography of  Nothing has better testified to the streak of illiberalism still coursing through Indian political life in the years since the Emergency than the documentaries of Anand Patwardhan. His target has shifted: from Gandhi’s supposedly liberal Congress Party to the rise of right-wing Hindu nationalism, now manifested by a BJP government whose prime minister, Narendra Modi, has turned Kashmir into a prison state and begun a mass expulsion of Muslims in Assam. But the form and political sensibility of Patwardhan’s work has remained: an engaged documentarian moving in contraflow to the ideas of the day.

Nothing has better testified to the streak of illiberalism still coursing through Indian political life in the years since the Emergency than the documentaries of Anand Patwardhan. His target has shifted: from Gandhi’s supposedly liberal Congress Party to the rise of right-wing Hindu nationalism, now manifested by a BJP government whose prime minister, Narendra Modi, has turned Kashmir into a prison state and begun a mass expulsion of Muslims in Assam. But the form and political sensibility of Patwardhan’s work has remained: an engaged documentarian moving in contraflow to the ideas of the day. In recent years, Jack Grieve of the department of English and linguistics at the University of Birmingham in England has embraced Twitter as a bountiful lode for looking at language-use patterns. One of his projects examined the regional popularity of profanity in the U.S. (“crap” is big in the center of the country; “f—” turns up more on the coasts).

In recent years, Jack Grieve of the department of English and linguistics at the University of Birmingham in England has embraced Twitter as a bountiful lode for looking at language-use patterns. One of his projects examined the regional popularity of profanity in the U.S. (“crap” is big in the center of the country; “f—” turns up more on the coasts).  It’s hot as fuck, said the friend who handed me Confessions Of The Fox, a faux-memoir set in eighteenth-century London. I was a little sceptical. After all, this was Jordy Rosenberg’s first novel. A queer theorist and historian of this period, he has re-written an eighteenth-century life from a trans perspective – a fool’s errand, murmured the cynic in me, to claim a world dominated by heteropatriarchy. Yet I found that as well as being hot as fuck, it was also something of a masterpiece.

It’s hot as fuck, said the friend who handed me Confessions Of The Fox, a faux-memoir set in eighteenth-century London. I was a little sceptical. After all, this was Jordy Rosenberg’s first novel. A queer theorist and historian of this period, he has re-written an eighteenth-century life from a trans perspective – a fool’s errand, murmured the cynic in me, to claim a world dominated by heteropatriarchy. Yet I found that as well as being hot as fuck, it was also something of a masterpiece. Like most people on Earth, Greta Thunberg is not a climate scientist. She has no formal scientific training of any type, nor does she possess any expert-level knowledge or expert-level skills in this regime. She has never worked on the problems or puzzles facing environmental scientists, atmospheric scientists, geophysicists, solar physicists, climatologists, meteorologists, or Earth scientists.

Like most people on Earth, Greta Thunberg is not a climate scientist. She has no formal scientific training of any type, nor does she possess any expert-level knowledge or expert-level skills in this regime. She has never worked on the problems or puzzles facing environmental scientists, atmospheric scientists, geophysicists, solar physicists, climatologists, meteorologists, or Earth scientists. Karachi feels like a city without a clearly defined past, or at least not one that has carried over into the present. In the 1950s it was known as the “Paris of the East,” but that impression has not aged well. In 1941, before partition, the city’s population was about 51% Hindu. Now it is virtually 0% Hindu, obliterating yet another feature of the city’s history. It is currently a mix of Pakistani ethnicities, including Sindhis (the home province), Punjabis, Pashtuns, the Baloch and many more — indeed, Pakistan in miniature.

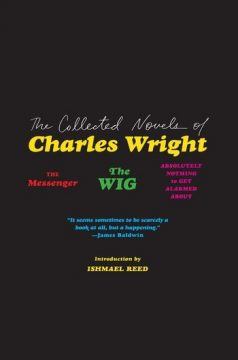

Karachi feels like a city without a clearly defined past, or at least not one that has carried over into the present. In the 1950s it was known as the “Paris of the East,” but that impression has not aged well. In 1941, before partition, the city’s population was about 51% Hindu. Now it is virtually 0% Hindu, obliterating yet another feature of the city’s history. It is currently a mix of Pakistani ethnicities, including Sindhis (the home province), Punjabis, Pashtuns, the Baloch and many more — indeed, Pakistan in miniature. The decades of near-silence that came in the wake of Charles Wright’s trilogy of short novels seem almost as aberrant and disquieting as the novels themselves. Wright died of heart failure at age seventy-six in October 2008, one month before Barack Obama’s election and thirty-five years after the publication of Absolutely Nothing to Get Alarmed About, the last of Wright’s novels, whose 1973 appearance came a decade after his debut, The Messenger. Wright clawed and strained from the margins of American existence for widespread acknowledgment, if not the fame his talent deserved. Cult-hood was the best he got, but it’s been enough. Through the dedication and (even) fervor of his steadfast readers, Wright’s sardonic, lyrical depictions of a young black intellectual’s odyssey through the lower depths of mid-twentieth-century New York City have somehow materialized in another century, much as Wright once imagined himself to move through time and space: “like an uncertain ghost through the white world.”

The decades of near-silence that came in the wake of Charles Wright’s trilogy of short novels seem almost as aberrant and disquieting as the novels themselves. Wright died of heart failure at age seventy-six in October 2008, one month before Barack Obama’s election and thirty-five years after the publication of Absolutely Nothing to Get Alarmed About, the last of Wright’s novels, whose 1973 appearance came a decade after his debut, The Messenger. Wright clawed and strained from the margins of American existence for widespread acknowledgment, if not the fame his talent deserved. Cult-hood was the best he got, but it’s been enough. Through the dedication and (even) fervor of his steadfast readers, Wright’s sardonic, lyrical depictions of a young black intellectual’s odyssey through the lower depths of mid-twentieth-century New York City have somehow materialized in another century, much as Wright once imagined himself to move through time and space: “like an uncertain ghost through the white world.”