Richard Reeves in The Guardian:

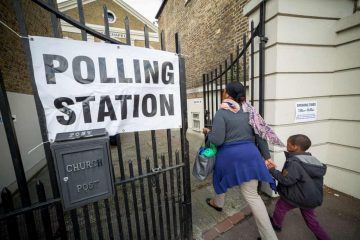

Capitalism reigns. But capitalism is in trouble. Therein lies the paradox of our age. For the first time in human history, a single economic system spans the globe. Of course there are differences between capitalism Chinese-style, American-style and Swedish-style. Close up, these differences can seem significant. But viewed through a wider lens, the distinctions blur. As the economist Branco Milanovic writes in his new book, Capitalism Alone, “the entire globe now operates according to the same economic principles – production organized for profit using legally free wage labor and mostly privately owned capital, with decentralized coordination”. After the fall of Soviet communism in 1989, and China’s embrace of the market, crowned by the nation’s entry into the World Trade Organization in 2001, it seemed, for a brief flicker of human history, that the world was converging on a political economy of free markets in liberal democracies. As it turned out, markets spread, but without necessarily bringing more democracy or liberalism along with them.

Capitalism reigns. But capitalism is in trouble. Therein lies the paradox of our age. For the first time in human history, a single economic system spans the globe. Of course there are differences between capitalism Chinese-style, American-style and Swedish-style. Close up, these differences can seem significant. But viewed through a wider lens, the distinctions blur. As the economist Branco Milanovic writes in his new book, Capitalism Alone, “the entire globe now operates according to the same economic principles – production organized for profit using legally free wage labor and mostly privately owned capital, with decentralized coordination”. After the fall of Soviet communism in 1989, and China’s embrace of the market, crowned by the nation’s entry into the World Trade Organization in 2001, it seemed, for a brief flicker of human history, that the world was converging on a political economy of free markets in liberal democracies. As it turned out, markets spread, but without necessarily bringing more democracy or liberalism along with them.

Capitalism without democracy was assumed to be at most a passing phase. Eventually, so western liberal thinking went, China and other Asian nations adopting what Milanovic calls “political capitalism” – free markets, but authoritarian politics – would have to adopt liberal political institutions, too. But, so far, the liberalization thesis remains unproven. China has successfully adopted a market system – and, even more importantly, a market culture – without liberal democratic institutions.

More here.

Of course, every revolution is unique and comparisons between them do not always yield useful insights. But

Of course, every revolution is unique and comparisons between them do not always yield useful insights. But  There has been quite a bit of prophesizing among pundits in the news media, on the

There has been quite a bit of prophesizing among pundits in the news media, on the As a microbiologist, Massimiliano Marvasi has spent years studying how microbes have defeated us. Many pathogens have evolved resistance to penicillin and other antimicrobial drugs, and now public health experts

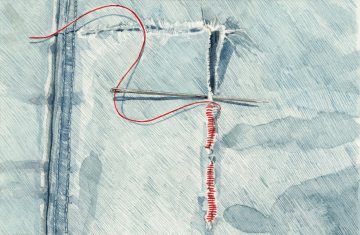

As a microbiologist, Massimiliano Marvasi has spent years studying how microbes have defeated us. Many pathogens have evolved resistance to penicillin and other antimicrobial drugs, and now public health experts  Several years ago, while living in London, England, my wife met Prince Charles at an event associated with the Prince’s Foundation, where she worked. She returned with two observations: First, the Prince of Wales used two fingers – index and middle – when he pointed. Second, Charles’s suit had visible signs of mending. A Google search fails to substantiate the double-barrelled gesture, but the Prince’s penchant for patching has been well documented. Last year, the journalist Marion Hume discovered a cardboard box containing more than 30 years of off-cuts and leftover materials from the Prince’s suits, tucked away in a corner at his Savile Row tailor, Anderson & Sheppard. “I have always believed in trying to keep as many of my clothes and shoes going for as long as possible … through patches and repairs,” he

Several years ago, while living in London, England, my wife met Prince Charles at an event associated with the Prince’s Foundation, where she worked. She returned with two observations: First, the Prince of Wales used two fingers – index and middle – when he pointed. Second, Charles’s suit had visible signs of mending. A Google search fails to substantiate the double-barrelled gesture, but the Prince’s penchant for patching has been well documented. Last year, the journalist Marion Hume discovered a cardboard box containing more than 30 years of off-cuts and leftover materials from the Prince’s suits, tucked away in a corner at his Savile Row tailor, Anderson & Sheppard. “I have always believed in trying to keep as many of my clothes and shoes going for as long as possible … through patches and repairs,” he  Self-replicating, bacterial life first appeared on Earth about 4 billion years ago. For most of Earth’s history, life remained at the single-celled level, and nothing like a nervous system existed until around 600 or 700 million years ago (MYA). In the attention schema theory, consciousness depends on the nervous system processing information in a specific way. The key to the theory, and I suspect the key to any advanced intelligence, is attention—the ability of the brain to focus its limited resources on a restricted piece of the world at any one time in order to process it in greater depth.

Self-replicating, bacterial life first appeared on Earth about 4 billion years ago. For most of Earth’s history, life remained at the single-celled level, and nothing like a nervous system existed until around 600 or 700 million years ago (MYA). In the attention schema theory, consciousness depends on the nervous system processing information in a specific way. The key to the theory, and I suspect the key to any advanced intelligence, is attention—the ability of the brain to focus its limited resources on a restricted piece of the world at any one time in order to process it in greater depth. The crowded room was awaiting one word: “Fire.”

The crowded room was awaiting one word: “Fire.” Nearly two decades before Boeing’s MCAS system crashed two of the plane-maker’s brand-new 737 MAX jets, Stan Sorscher knew his company’s increasingly toxic mode of operating would create a disaster of some kind. A long and proud “safety culture” was rapidly being replaced, he argued, with “a culture of financial bullshit, a culture of groupthink.”

Nearly two decades before Boeing’s MCAS system crashed two of the plane-maker’s brand-new 737 MAX jets, Stan Sorscher knew his company’s increasingly toxic mode of operating would create a disaster of some kind. A long and proud “safety culture” was rapidly being replaced, he argued, with “a culture of financial bullshit, a culture of groupthink.” To experience a thing

To experience a thing Capitalism reigns. But capitalism is in trouble. Therein lies the paradox of our age. For the first time in human history, a single economic system spans the globe. Of course there are differences between capitalism Chinese-style, American-style and Swedish-style. Close up, these differences can seem significant. But viewed through a wider lens, the distinctions blur. As the economist Branco Milanovic writes in his new book, Capitalism Alone, “the entire globe now operates according to the same economic principles – production organized for profit using legally free wage labor and mostly privately owned capital, with decentralized coordination”. After the fall of Soviet communism in 1989, and China’s embrace of the market, crowned by the nation’s entry into the World Trade Organization in 2001, it seemed, for a brief flicker of human history, that the world was converging on a political economy of free markets in liberal democracies. As it turned out, markets spread, but without necessarily bringing more democracy or liberalism along with them.

Capitalism reigns. But capitalism is in trouble. Therein lies the paradox of our age. For the first time in human history, a single economic system spans the globe. Of course there are differences between capitalism Chinese-style, American-style and Swedish-style. Close up, these differences can seem significant. But viewed through a wider lens, the distinctions blur. As the economist Branco Milanovic writes in his new book, Capitalism Alone, “the entire globe now operates according to the same economic principles – production organized for profit using legally free wage labor and mostly privately owned capital, with decentralized coordination”. After the fall of Soviet communism in 1989, and China’s embrace of the market, crowned by the nation’s entry into the World Trade Organization in 2001, it seemed, for a brief flicker of human history, that the world was converging on a political economy of free markets in liberal democracies. As it turned out, markets spread, but without necessarily bringing more democracy or liberalism along with them. Eric D. Weitz in the LA Review of Books:

Eric D. Weitz in the LA Review of Books: Thomas Frank in the NYT:

Thomas Frank in the NYT: Richard Seymour in The Guardian:

Richard Seymour in The Guardian: