Andrew Anthony in The Guardian:

Some years and several books ago, the New Yorker journalist Malcolm Gladwell moved from being a talented writer to a cultural phenomenon. He has practically invented a genre of nonfiction writing: the finely turned counterintuitive narrative underpinned by social science studies. Or if not the inventor then someone so closely associated with the form that it could fall under the title of Gladwellian.

Some years and several books ago, the New Yorker journalist Malcolm Gladwell moved from being a talented writer to a cultural phenomenon. He has practically invented a genre of nonfiction writing: the finely turned counterintuitive narrative underpinned by social science studies. Or if not the inventor then someone so closely associated with the form that it could fall under the title of Gladwellian.

His latest book, Talking to Strangers, is a typically roundabout exploration of the assumptions and mistakes we make when dealing with people we don’t know. If that sounds like a rather vague area of study, that’s because in many respects it is – there are all manner of definitional and cultural issues through which Gladwell boldly navigates a rather convenient path. But in doing so he crafts a compelling story, stopping off at prewar appeasement, paedophilia, espionage, the TV show Friends, the Amanda Knox and Bernie Madoff cases, suicide and Sylvia Plath, torture and Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, before coming to a somewhat pat conclusion. The tale begins with Sandra Bland, the African American woman who in July 2015 was stopped by a traffic cop in a small Texas town. She was just about to begin a job at Prairie View A&M University, when a police car accelerated up behind her. Doing what almost all of us would have done, she moved aside to let the car pass. And just like most of us in that situation, she didn’t bother indicating. It was on that technicality that the cop, Brian Encinia, ordered her to pull over.

More here.

Three myths about morality remain alluring: only humans act on moral emotions, moral precepts are divine in origin, and learning to behave morally goes against our thoroughly selfish nature. Converging data from many sciences, including ethology, anthropology, genetics, and neuroscience, have challenged all three of these myths. First, self-sacrifice, given the pressing needs of close kin or conspecifics to whom they are attached, has been documented in many mammalian species—wolves, marmosets, dolphins, and even rodents. Birds display it too. In sharp contrast, reptiles show no hint of this impulse.

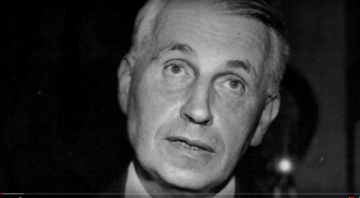

Three myths about morality remain alluring: only humans act on moral emotions, moral precepts are divine in origin, and learning to behave morally goes against our thoroughly selfish nature. Converging data from many sciences, including ethology, anthropology, genetics, and neuroscience, have challenged all three of these myths. First, self-sacrifice, given the pressing needs of close kin or conspecifics to whom they are attached, has been documented in many mammalian species—wolves, marmosets, dolphins, and even rodents. Birds display it too. In sharp contrast, reptiles show no hint of this impulse. Like other teachers and sages I’d known and apprenticed myself to for seasons of my life, Bloom performed, but what he didn’t perform was pedagogy or teaching, not for himself and not for us. He just did readings, in the Bloom way, which was an ongoing drama, in words, between the work at hand and the absent works, lines and phrases that the work had brought itself into being from. This isn’t the same as watered down “intertextuality” or “influence studies” or, god forbid, some kind of seminar or salon-like conversation. It wasn’t “New Critical” thing-in-itself close reading, because poems weren’t things in themselves, they were living subjects, and as full of contradictions and private dramas and unconscious desires and hauntings as any other. While some critics thought about the “political unconscious” and others of just the human unconscious, Bloom found a way to surface the poetic unconscious.

Like other teachers and sages I’d known and apprenticed myself to for seasons of my life, Bloom performed, but what he didn’t perform was pedagogy or teaching, not for himself and not for us. He just did readings, in the Bloom way, which was an ongoing drama, in words, between the work at hand and the absent works, lines and phrases that the work had brought itself into being from. This isn’t the same as watered down “intertextuality” or “influence studies” or, god forbid, some kind of seminar or salon-like conversation. It wasn’t “New Critical” thing-in-itself close reading, because poems weren’t things in themselves, they were living subjects, and as full of contradictions and private dramas and unconscious desires and hauntings as any other. While some critics thought about the “political unconscious” and others of just the human unconscious, Bloom found a way to surface the poetic unconscious. Warning: this story is about death. You might want to click away now.

Warning: this story is about death. You might want to click away now. Is a penchant for moral posturing part of a newspaper columnist’s job description? Sometimes it seems so. But if there were a prize for self-indulgent journalistic garment renting, Bret Stephens of The New York Times would certainly retire the trophy.

Is a penchant for moral posturing part of a newspaper columnist’s job description? Sometimes it seems so. But if there were a prize for self-indulgent journalistic garment renting, Bret Stephens of The New York Times would certainly retire the trophy.  The question that I’ve been perplexed by for a long time has to do with moral motivation. Where does it come from? Is moral motivation unique to the human animal or are there others? It’s clear at this point that moral motivation is part of what we are genetically equipped with, and that we share this with mammals, in general, and birds. In the case of humans, our moral behavior is more complex, which is probably because we have bigger brains. We have more neurons than, say, a chimpanzee, a mouse, or a rat, but we have all the same structures. There is no special structure for morality tucked in there.

The question that I’ve been perplexed by for a long time has to do with moral motivation. Where does it come from? Is moral motivation unique to the human animal or are there others? It’s clear at this point that moral motivation is part of what we are genetically equipped with, and that we share this with mammals, in general, and birds. In the case of humans, our moral behavior is more complex, which is probably because we have bigger brains. We have more neurons than, say, a chimpanzee, a mouse, or a rat, but we have all the same structures. There is no special structure for morality tucked in there. The idea for the Aspen Institute first emerged after the second world war. In 1949 Walter Paepcke, a Chicago businessman, planned a bicentennial celebration of the life of Goethe. Paepcke and his wife, Elizabeth, chose Aspen because it was both beautiful and easily accessible from either coast. The couple felt there was an “urgent need” to understand Goethe’s thought: the world, still recovering from the war, had been cleft in half by the ideological battle between communism and capitalism. The Paepckes saw Goethe as a prime advocate of the underlying unity of mankind. He also worried about the corrosive effects of rapidly proliferating wealth. The Paepckes imagined that Aspen could become an “American Athens”, educating an upper-crust elite hungry for spiritual sustenance in the newly ascendant nation. Such work was vital “if the people of America and other nations are to strengthen their will for decency, ethical conduct and morality in a modern world”. Herbert Hoover, the former president, was named honorary chairman; Thomas Mann joined the board of directors.

The idea for the Aspen Institute first emerged after the second world war. In 1949 Walter Paepcke, a Chicago businessman, planned a bicentennial celebration of the life of Goethe. Paepcke and his wife, Elizabeth, chose Aspen because it was both beautiful and easily accessible from either coast. The couple felt there was an “urgent need” to understand Goethe’s thought: the world, still recovering from the war, had been cleft in half by the ideological battle between communism and capitalism. The Paepckes saw Goethe as a prime advocate of the underlying unity of mankind. He also worried about the corrosive effects of rapidly proliferating wealth. The Paepckes imagined that Aspen could become an “American Athens”, educating an upper-crust elite hungry for spiritual sustenance in the newly ascendant nation. Such work was vital “if the people of America and other nations are to strengthen their will for decency, ethical conduct and morality in a modern world”. Herbert Hoover, the former president, was named honorary chairman; Thomas Mann joined the board of directors. In the depths of winter, water temperatures in the ice-covered Arctic Ocean can sink below zero. That’s cold enough to freeze many fish, but the conditions don’t trouble the cod. A protein in its blood and tissues binds to tiny ice crystals and stops them from growing. Where codfish got this talent was a puzzle that evolutionary biologist Helle Tessand Baalsrud wanted to solve. She and her team at the University of Oslo searched the genomes of the Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua) and several of its closest relatives, thinking they would track down the cousins of the antifreeze gene. None showed up. Baalsrud, who at the time was a new parent, worried that her lack of sleep was causing her to miss something obvious.

In the depths of winter, water temperatures in the ice-covered Arctic Ocean can sink below zero. That’s cold enough to freeze many fish, but the conditions don’t trouble the cod. A protein in its blood and tissues binds to tiny ice crystals and stops them from growing. Where codfish got this talent was a puzzle that evolutionary biologist Helle Tessand Baalsrud wanted to solve. She and her team at the University of Oslo searched the genomes of the Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua) and several of its closest relatives, thinking they would track down the cousins of the antifreeze gene. None showed up. Baalsrud, who at the time was a new parent, worried that her lack of sleep was causing her to miss something obvious. Ethan Weinstein in 3:AM Magazine:

Ethan Weinstein in 3:AM Magazine: Astra Taylor in the New York Times:

Astra Taylor in the New York Times: Lenore Palladino in Boston Review, with responses from William Lazonick, Julius Krein, Lauren Jacobs, Michael Lind, Isabelle Ferreras, James Galbraith and Katharina Pistor:

Lenore Palladino in Boston Review, with responses from William Lazonick, Julius Krein, Lauren Jacobs, Michael Lind, Isabelle Ferreras, James Galbraith and Katharina Pistor: Philip Mader, Richard Jolly, Maren Duvendack and Solene Morvant-Roux over at the Institute for Development Studies:

Philip Mader, Richard Jolly, Maren Duvendack and Solene Morvant-Roux over at the Institute for Development Studies: Edit Schlaffer felt as if she was part of history in the making when 60 mothers from this southern region of Germany recently received their MotherSchools diploma from Bavaria’s social minister. Ms. Schlaffer initiated her MotherSchools syllabus nine years ago for women in Tajikistan who were concerned about Islamic extremists recruiting their children. The program has since become a global movement whose goal is to fight extremism not with soldiers, but with mothers. And now, Germany has its first batch of graduates – women with roots from Syria to Algeria. They’ve learned not only how to better detect, and respond to, early signs of radicalization, but also how to better connect with their sons. When Ms. Schlaffer initially met them, the women had tended to be shy, their hands often crossed on their knees and their heads bent down. But on graduation day, donning colorful headscarves and shiny suits, they mingled with top brass politicians in a castle overlooking the Main River here.

Edit Schlaffer felt as if she was part of history in the making when 60 mothers from this southern region of Germany recently received their MotherSchools diploma from Bavaria’s social minister. Ms. Schlaffer initiated her MotherSchools syllabus nine years ago for women in Tajikistan who were concerned about Islamic extremists recruiting their children. The program has since become a global movement whose goal is to fight extremism not with soldiers, but with mothers. And now, Germany has its first batch of graduates – women with roots from Syria to Algeria. They’ve learned not only how to better detect, and respond to, early signs of radicalization, but also how to better connect with their sons. When Ms. Schlaffer initially met them, the women had tended to be shy, their hands often crossed on their knees and their heads bent down. But on graduation day, donning colorful headscarves and shiny suits, they mingled with top brass politicians in a castle overlooking the Main River here. Back in the 1940s, C. S. Lewis remarked on a trend that he saw gaining steam even among some of his better pupils at Oxford: a belief that books penned by the greatest minds of the previous two or three millennia could be grasped only by credentialed professionals. This instinct steered them away from the satisfactions of primary literature and into the swamps of secondary works expounding upon the original sources. “I have found as a tutor in English Literature,” Lewis wrote, “that if the average student wants to find out something about Platonism, the very last thing he thinks of doing is to take a translation of Plato off the library shelf and read the Symposium. He would rather read some dreary modern book ten times as long, all about ‘isms’ and influences and only once in twelve pages telling him what Plato actually said.” Lewis was not denigrating commentaries; he wrote some formidable ones himself. He was merely making the point that most great writers of the distant past wrote to be read and apprehended by curious minds, not merely to provide fodder for exams and dissertations.

Back in the 1940s, C. S. Lewis remarked on a trend that he saw gaining steam even among some of his better pupils at Oxford: a belief that books penned by the greatest minds of the previous two or three millennia could be grasped only by credentialed professionals. This instinct steered them away from the satisfactions of primary literature and into the swamps of secondary works expounding upon the original sources. “I have found as a tutor in English Literature,” Lewis wrote, “that if the average student wants to find out something about Platonism, the very last thing he thinks of doing is to take a translation of Plato off the library shelf and read the Symposium. He would rather read some dreary modern book ten times as long, all about ‘isms’ and influences and only once in twelve pages telling him what Plato actually said.” Lewis was not denigrating commentaries; he wrote some formidable ones himself. He was merely making the point that most great writers of the distant past wrote to be read and apprehended by curious minds, not merely to provide fodder for exams and dissertations. About 10 years ago, I began to get impatient with disability studies. The field was still relatively young, but it seemed devoted almost entirely to analyzing how disability was represented – in art, in culture, in politics, et cetera – especially in the case of physical disability. This, I thought, fell short of the field’s promise for literary studies. Where, I wondered, was the field’s equivalent of Epistemology of the Closet, the book in which Eve Sedgwick showed us how to ‘queer’ texts, such that we will never read a narrative silence or lacuna the same way again? Put another way: I wanted a book that showed how an understanding of disability changes the way we read.

About 10 years ago, I began to get impatient with disability studies. The field was still relatively young, but it seemed devoted almost entirely to analyzing how disability was represented – in art, in culture, in politics, et cetera – especially in the case of physical disability. This, I thought, fell short of the field’s promise for literary studies. Where, I wondered, was the field’s equivalent of Epistemology of the Closet, the book in which Eve Sedgwick showed us how to ‘queer’ texts, such that we will never read a narrative silence or lacuna the same way again? Put another way: I wanted a book that showed how an understanding of disability changes the way we read. Ordinary physical theories tell you what a system is and how it evolves over time. Quantum mechanics does this as well, but it also comes with an entirely new set of rules, governing what happens when systems are observed or measured. Most notably, measurement outcomes cannot be predicted with perfect confidence, even in principle. The best we can do is to calculate the probability of obtaining each possible outcome, according to what’s called the Born rule: The wave function assigns an “amplitude” to each measurement outcome, and the probability of getting that result is equal to the amplitude squared. This feature is what led Albert Einstein to complain about God playing dice with the universe.

Ordinary physical theories tell you what a system is and how it evolves over time. Quantum mechanics does this as well, but it also comes with an entirely new set of rules, governing what happens when systems are observed or measured. Most notably, measurement outcomes cannot be predicted with perfect confidence, even in principle. The best we can do is to calculate the probability of obtaining each possible outcome, according to what’s called the Born rule: The wave function assigns an “amplitude” to each measurement outcome, and the probability of getting that result is equal to the amplitude squared. This feature is what led Albert Einstein to complain about God playing dice with the universe.