Adam Gaffney in the Boston Review:

In the spring of 2009, with the battle over the Affordable Care Act (ACA) in full swing, President Barack Obama called his aides into the oval office for an unusual meeting. As the New York Times reported, the topic of conversation was a recent New Yorker essay titled the “The Cost Conundrum.” It was written by the Harvard surgeon and writer Atul Gawande, now the CEO of Haven—the new Amazon-Berkshire Hathaway-JPMorgan Chase health care venture. His influential story—“required reading in the White House,” the Times called it—described a journey down into the heart of health care darkness: McAllen, Texas, a poor city at the southern tip of the state with some of the highest health care spending in the nation.

In the spring of 2009, with the battle over the Affordable Care Act (ACA) in full swing, President Barack Obama called his aides into the oval office for an unusual meeting. As the New York Times reported, the topic of conversation was a recent New Yorker essay titled the “The Cost Conundrum.” It was written by the Harvard surgeon and writer Atul Gawande, now the CEO of Haven—the new Amazon-Berkshire Hathaway-JPMorgan Chase health care venture. His influential story—“required reading in the White House,” the Times called it—described a journey down into the heart of health care darkness: McAllen, Texas, a poor city at the southern tip of the state with some of the highest health care spending in the nation.

What was the root of McAllen’s high costs—and, by extension, of all of ours? Gawande quickly cracks the case. “There is overutilization here,” a general surgeon tells him during the trip, “pure and simple.” Patients went to the doctor too often, had too many operations, spent too much time at the hospital, and received too many days of home care. “The primary cause of McAllen’s extreme costs,” Gawande concludes, “was, very simply, the across-the-board overuse of medicine.”

More here.

I have a practical build. I’m petite, compact. My stomach is tight, small, undemanding. My lungs and my shoulders are strong. I’m not on any prescriptions—not even the pill—and I don’t wear glasses. I cut my hair with clippers, once every three months, and I use almost no makeup. My teeth are healthy, perhaps a bit uneven, but intact, and I have just one old filling, which I believe is located in my lower left canine. My liver function is within the normal range. As is my pancreas. Both my right and left kidneys are in great shape. My abdominal aorta is normal. My bladder works. Hemoglobin 12.7. Leukocytes 4.5. Hematocrit 41.6. Platelets 228. Cholesterol 204. Creatinine 1.0. Bilirubin 4.2. And so on. My IQ—if you put any stock in that kind of thing—is 121; it’s passable. My spatial reasoning is particularly advanced, almost eidetic, though my laterality is lousy. Personality unstable, or not entirely reliable. Age all in your mind. Gender grammatical. I actually buy my books in paperback, so that I can leave them without remorse on the platform, for someone else to find. I don’t collect anything.

I have a practical build. I’m petite, compact. My stomach is tight, small, undemanding. My lungs and my shoulders are strong. I’m not on any prescriptions—not even the pill—and I don’t wear glasses. I cut my hair with clippers, once every three months, and I use almost no makeup. My teeth are healthy, perhaps a bit uneven, but intact, and I have just one old filling, which I believe is located in my lower left canine. My liver function is within the normal range. As is my pancreas. Both my right and left kidneys are in great shape. My abdominal aorta is normal. My bladder works. Hemoglobin 12.7. Leukocytes 4.5. Hematocrit 41.6. Platelets 228. Cholesterol 204. Creatinine 1.0. Bilirubin 4.2. And so on. My IQ—if you put any stock in that kind of thing—is 121; it’s passable. My spatial reasoning is particularly advanced, almost eidetic, though my laterality is lousy. Personality unstable, or not entirely reliable. Age all in your mind. Gender grammatical. I actually buy my books in paperback, so that I can leave them without remorse on the platform, for someone else to find. I don’t collect anything.

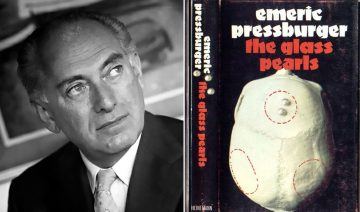

In the aftermath of the dissolution of Pressburger and Powell’s partnership in the late fifties, Pressburger turned to novels. The first, Killing a Mouse on a Sunday, published in 1961, is set during the aftermath of the Spanish Civil War and tells the story of a once notorious bandit, now a tired old man living in exile in France who resolves to cross the border back into Spain, despite the danger to his life, to visit his dying mother. In an interview published in the Daily Mail at the time, Pressburger explained that after years of “communal” creativity in the world of film, he wanted to “prove I could do something on my own.” The novel met with favorable reviews, was quickly translated into a dozen languages, and adapted for the big screen in 1964 as Behold a Pale Horse, directed by Fred Zinnemann and starring Gregory Peck, Omar Sharif, and Anthony Quinn. (That the film itself died a quick death didn’t really matter.) Everything was set for Pressburger’s second novel to build on this success. Unfortunately, this wasn’t to be. The Glass Pearls, published in 1966, was a much darker, grittier tale about a Nazi war criminal hiding in plain sight in the dingy streets of London’s Pimlico. It garnered one lone review, a damning write-up in the Times Literary Supplement. The book barely sold its initial print run of four thousand copies, immediately sinking without a trace. And yet, despite the reception it received at the time, The Glass Pearls is a truly remarkable work. It deserves to be recognized both for its own virtuosity, and as an important addition to the genre of Holocaust literature.

In the aftermath of the dissolution of Pressburger and Powell’s partnership in the late fifties, Pressburger turned to novels. The first, Killing a Mouse on a Sunday, published in 1961, is set during the aftermath of the Spanish Civil War and tells the story of a once notorious bandit, now a tired old man living in exile in France who resolves to cross the border back into Spain, despite the danger to his life, to visit his dying mother. In an interview published in the Daily Mail at the time, Pressburger explained that after years of “communal” creativity in the world of film, he wanted to “prove I could do something on my own.” The novel met with favorable reviews, was quickly translated into a dozen languages, and adapted for the big screen in 1964 as Behold a Pale Horse, directed by Fred Zinnemann and starring Gregory Peck, Omar Sharif, and Anthony Quinn. (That the film itself died a quick death didn’t really matter.) Everything was set for Pressburger’s second novel to build on this success. Unfortunately, this wasn’t to be. The Glass Pearls, published in 1966, was a much darker, grittier tale about a Nazi war criminal hiding in plain sight in the dingy streets of London’s Pimlico. It garnered one lone review, a damning write-up in the Times Literary Supplement. The book barely sold its initial print run of four thousand copies, immediately sinking without a trace. And yet, despite the reception it received at the time, The Glass Pearls is a truly remarkable work. It deserves to be recognized both for its own virtuosity, and as an important addition to the genre of Holocaust literature. In August, marine biologists Johnny Gaskell and Peter Mumby and a team of researchers boarded a boat headed into unknown waters off the coasts of Australia. For 14 long hours, they ploughed over 200 nautical miles, a Google Maps cache as their only guide. Just before dawn, they arrived at their destination of a previously uncharted blue hole—a cavernous opening descending through the seafloor. After the rough night, Mumby was rewarded with something he hadn’t seen in his 30-year career. The reef surrounding the blue hole had nearly 100 percent healthy coral cover. Such a find is rare in the Great Barrier Reef, where coral bleaching events in 2016 and 2017 led to headlines

In August, marine biologists Johnny Gaskell and Peter Mumby and a team of researchers boarded a boat headed into unknown waters off the coasts of Australia. For 14 long hours, they ploughed over 200 nautical miles, a Google Maps cache as their only guide. Just before dawn, they arrived at their destination of a previously uncharted blue hole—a cavernous opening descending through the seafloor. After the rough night, Mumby was rewarded with something he hadn’t seen in his 30-year career. The reef surrounding the blue hole had nearly 100 percent healthy coral cover. Such a find is rare in the Great Barrier Reef, where coral bleaching events in 2016 and 2017 led to headlines  The car, wrote the French thinker André Gorz, “supports in everyone the illusion that each individual can seek his or her own benefit at the expense of everyone else”.

The car, wrote the French thinker André Gorz, “supports in everyone the illusion that each individual can seek his or her own benefit at the expense of everyone else”.  Thomas Piketty’s new book

Thomas Piketty’s new book  Some sporting moments achieve mythical status because of their sheer audacity. Muhammad Ali’s

Some sporting moments achieve mythical status because of their sheer audacity. Muhammad Ali’s As it is becoming obvious that political responses to global warming such as the Paris treaty are not working, environmentalists are urging us to consider the climate impact of our personal actions. Don’t eat meat, don’t drive a gasoline-powered car and don’t fly, they say. But these individual actions won’t make a substantial difference to our planet, and such demands divert attention away from the solutions that are needed.

As it is becoming obvious that political responses to global warming such as the Paris treaty are not working, environmentalists are urging us to consider the climate impact of our personal actions. Don’t eat meat, don’t drive a gasoline-powered car and don’t fly, they say. But these individual actions won’t make a substantial difference to our planet, and such demands divert attention away from the solutions that are needed. How do we understand that our 100,000-fold excess of numbers on this planet, plus what we do to feed ourselves, makes us a tumor on the body of the planet? I don’t want the future that involves some end to us, which is a kind of surgery of the planet. That’s not anybody’s wish. How do we revert ourselves to normal while we can? How do we re-enter the world of natural selection, not by punishing each other, but by volunteering to take success as meaning success and survival of the future, not success in stuff now? How do we do that? We don’t have a language for that.

How do we understand that our 100,000-fold excess of numbers on this planet, plus what we do to feed ourselves, makes us a tumor on the body of the planet? I don’t want the future that involves some end to us, which is a kind of surgery of the planet. That’s not anybody’s wish. How do we revert ourselves to normal while we can? How do we re-enter the world of natural selection, not by punishing each other, but by volunteering to take success as meaning success and survival of the future, not success in stuff now? How do we do that? We don’t have a language for that. Tech mogul Marc Benioff has been winning media accolades for his declaration that “capitalism, as we know it, is dead.” The billionaire founder and CEO of Salesforce, a cloud-based customer-relations company, has launched an advertising blitz promoting his new book, Trailblazer, which calls for a “more fair, equal and sustainable capitalism,” as Benioff put it in a New York Times op-ed on Monday. This “new capitalism” would not “just take from society but truly give back and have a positive impact,” Benioff maintains.

Tech mogul Marc Benioff has been winning media accolades for his declaration that “capitalism, as we know it, is dead.” The billionaire founder and CEO of Salesforce, a cloud-based customer-relations company, has launched an advertising blitz promoting his new book, Trailblazer, which calls for a “more fair, equal and sustainable capitalism,” as Benioff put it in a New York Times op-ed on Monday. This “new capitalism” would not “just take from society but truly give back and have a positive impact,” Benioff maintains.

Throughout my career as a neurosurgeon, I have worked closely with oncologists. Many of my patients have cancer of the brain — one of the deadliest of the near-infinite number of cancers. I have always viewed my oncological colleagues with complicated, contradictory feelings. On the one hand, I’m in awe of their work, which can be so emotionally demanding. On the other, I suspect they don’t always know when to stop.

Throughout my career as a neurosurgeon, I have worked closely with oncologists. Many of my patients have cancer of the brain — one of the deadliest of the near-infinite number of cancers. I have always viewed my oncological colleagues with complicated, contradictory feelings. On the one hand, I’m in awe of their work, which can be so emotionally demanding. On the other, I suspect they don’t always know when to stop. Unlike Hillary Clinton, who used the same title for her memoir,

Unlike Hillary Clinton, who used the same title for her memoir,  In New York, where I live, whenever there’s a big holiday weekend, the traffic on Friday as folks leave town turns much of Manhattan into a hot, fume-filled parking lot. On those days, one can often walk faster than the traffic is moving. That may be the exception, but congestion in many cities has reached the point where getting around by car at certain times of day is almost not an option.

In New York, where I live, whenever there’s a big holiday weekend, the traffic on Friday as folks leave town turns much of Manhattan into a hot, fume-filled parking lot. On those days, one can often walk faster than the traffic is moving. That may be the exception, but congestion in many cities has reached the point where getting around by car at certain times of day is almost not an option.