Christopher Sorrentino at Bookforum:

Unfinished Business does not present as a work of literary criticism per se. While it is concerned with interpretation and meaning, its fundamental focus is on that most peculiar of phenomena, the way that texts appear to change as we reread them throughout our lives. The texts, of course, do no such thing; we’re the ones doing the changing, and this relatively banal truth is Gornick’s entry point, using select works to illustrate the effects of lived life as measured against the yardstick of that relatively stable artifact, the book. In this context, the books and authors Gornick treats are largely irrelevant: Gornick has selected them for the glimpse each provides of the reexaminations of herself and her mind that her rereadings have prompted, or that have prompted the rereadings. I note this because I need to confess my own unfamiliarity with many of the books she writes about; my own experience of Unfinished Business didn’t suffer on account of my ignorance.

Unfinished Business does not present as a work of literary criticism per se. While it is concerned with interpretation and meaning, its fundamental focus is on that most peculiar of phenomena, the way that texts appear to change as we reread them throughout our lives. The texts, of course, do no such thing; we’re the ones doing the changing, and this relatively banal truth is Gornick’s entry point, using select works to illustrate the effects of lived life as measured against the yardstick of that relatively stable artifact, the book. In this context, the books and authors Gornick treats are largely irrelevant: Gornick has selected them for the glimpse each provides of the reexaminations of herself and her mind that her rereadings have prompted, or that have prompted the rereadings. I note this because I need to confess my own unfamiliarity with many of the books she writes about; my own experience of Unfinished Business didn’t suffer on account of my ignorance.

more here.

It was driven home to me repeatedly in my early efforts to build an investment strategy that, quite apart from the question of whether the quest for wealth is sinful in the sense understood by the painters of vanitas scenes, it is most certainly and irredeemably unethical. All of the relatively low-risk index funds that are the bedrock of a sound investment portfolio are spread across so many different kinds of companies that one could not possibly keep track of all the ways each of them violates the rights and sanctity of its employees, of its customers, of the environment. And even if you are investing in individual companies (while maintaining healthy risk-buffering diversification, etc.), you must accept that the only way for you as a shareholder to get ahead is for those companies to continue to grow, even when the limits of whatever good they might do for the world, assuming they were doing good for the world to begin with, have been surpassed. That is just how capitalism works: an unceasing imperative for growth beyond any natural necessity, leading to the desolation of the earth and the exhaustion of its resources. I am a part of that now, too. I always was, to some extent, with every purchase I made, every light switch I flipped. But to become an active investor is to make it official, to solemnify the contract, as if in blood.

It was driven home to me repeatedly in my early efforts to build an investment strategy that, quite apart from the question of whether the quest for wealth is sinful in the sense understood by the painters of vanitas scenes, it is most certainly and irredeemably unethical. All of the relatively low-risk index funds that are the bedrock of a sound investment portfolio are spread across so many different kinds of companies that one could not possibly keep track of all the ways each of them violates the rights and sanctity of its employees, of its customers, of the environment. And even if you are investing in individual companies (while maintaining healthy risk-buffering diversification, etc.), you must accept that the only way for you as a shareholder to get ahead is for those companies to continue to grow, even when the limits of whatever good they might do for the world, assuming they were doing good for the world to begin with, have been surpassed. That is just how capitalism works: an unceasing imperative for growth beyond any natural necessity, leading to the desolation of the earth and the exhaustion of its resources. I am a part of that now, too. I always was, to some extent, with every purchase I made, every light switch I flipped. But to become an active investor is to make it official, to solemnify the contract, as if in blood. Lamenting

Lamenting  As the global tide of populism challenges the very idea of liberal democracy, Donald Trump’s visit to India highlighted how Trump and India’s prime minister,

As the global tide of populism challenges the very idea of liberal democracy, Donald Trump’s visit to India highlighted how Trump and India’s prime minister,  By the time the British artist Isaac Julien’s iconic short essay-film “Looking for Langston” was released, in 1989, Julien’s ostensible subject, the enigmatic poet and race man Langston Hughes, had been dead for twenty-two years, but the search for his “real” story was still ongoing. There was a sense—particularly among gay men of color, like Julien, who had so few “out” ancestors and wanted to claim the prolific, uneven, but significant writer as one of their own—that some essential things about Hughes had been obscured or disfigured in his work and his memoirs. Born in Joplin, Missouri, in 1902, and transplanted to New York City as a strikingly handsome nineteen-year-old, Hughes became, with the publication of his first book of poems, “The Weary Blues” (1926), a prominent New Negro: modern, pluralistic in his beliefs, and a member of what the folklorist and novelist Zora Neale Hurston called “the niggerati,” a loosely formed alliance of black writers and intellectuals that included Hurston, the author and diplomat James Weldon Johnson, the openly gay poet and artist Richard Bruce Nugent, and the novelists Nella Larsen, Jessie Fauset, and Wallace Thurman (whose 1929 novel about color fixation among blacks, “The Blacker the Berry,” conveys some of the energy of the time).

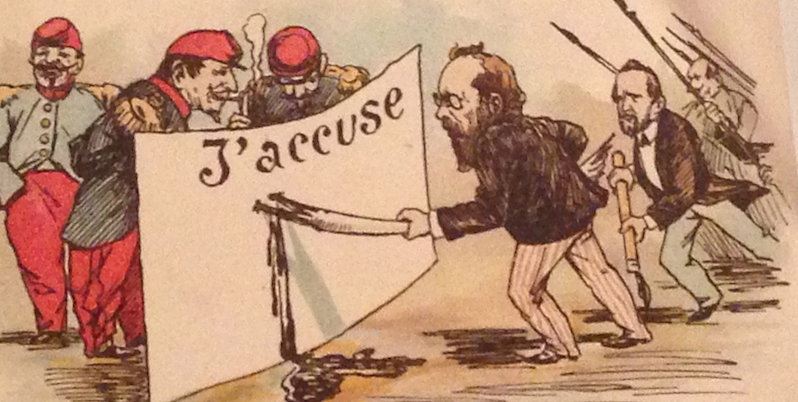

By the time the British artist Isaac Julien’s iconic short essay-film “Looking for Langston” was released, in 1989, Julien’s ostensible subject, the enigmatic poet and race man Langston Hughes, had been dead for twenty-two years, but the search for his “real” story was still ongoing. There was a sense—particularly among gay men of color, like Julien, who had so few “out” ancestors and wanted to claim the prolific, uneven, but significant writer as one of their own—that some essential things about Hughes had been obscured or disfigured in his work and his memoirs. Born in Joplin, Missouri, in 1902, and transplanted to New York City as a strikingly handsome nineteen-year-old, Hughes became, with the publication of his first book of poems, “The Weary Blues” (1926), a prominent New Negro: modern, pluralistic in his beliefs, and a member of what the folklorist and novelist Zora Neale Hurston called “the niggerati,” a loosely formed alliance of black writers and intellectuals that included Hurston, the author and diplomat James Weldon Johnson, the openly gay poet and artist Richard Bruce Nugent, and the novelists Nella Larsen, Jessie Fauset, and Wallace Thurman (whose 1929 novel about color fixation among blacks, “The Blacker the Berry,” conveys some of the energy of the time). Merrie England, the Golden Age, la Belle Epoque: such shiny brand names are always coined retrospectively. No one in Paris ever said to one another, in 1895 or 1900, “We’re living in the Belle Epoque, better make the most of it.” The phrase describing that time of peace between the catastrophic French defeat of 1870–71 and the catastrophic French victory of 1914–18 didn’t come into the language until 1940–41, after another French defeat. It was the title of a radio program which morphed into a live musical-theater show: a feel-good coinage and a feel-good distraction which also played up to certain German preconceptions about oh-la-la, can-can France.

Merrie England, the Golden Age, la Belle Epoque: such shiny brand names are always coined retrospectively. No one in Paris ever said to one another, in 1895 or 1900, “We’re living in the Belle Epoque, better make the most of it.” The phrase describing that time of peace between the catastrophic French defeat of 1870–71 and the catastrophic French victory of 1914–18 didn’t come into the language until 1940–41, after another French defeat. It was the title of a radio program which morphed into a live musical-theater show: a feel-good coinage and a feel-good distraction which also played up to certain German preconceptions about oh-la-la, can-can France.

A newly identified coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 (formerly 2019-nCoV) has been spreading in China, and has now reached multiple other countries. Here’s what you need to know about the virus and the disease it causes, called COVID-19.

A newly identified coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 (formerly 2019-nCoV) has been spreading in China, and has now reached multiple other countries. Here’s what you need to know about the virus and the disease it causes, called COVID-19. BREATHING FINE PARTICLES

BREATHING FINE PARTICLES Pádraig: Well, I think that language used well becomes its own scripture. And we’re in need of all kinds of new scriptures. In poetry, there is an attempt to create a scripture that’s sufficient for the moment. But for the poet, and for anybody that’s reading that poet’s work, there is a recognition to say, “These words haven’t been put in the right way for me yet, so therefore I’m going to do it myself, or I’m going to read around to see who has done it.” And that that can bless the human experience and also create the human experience. By feeling created and validated, to be made—to be truthed into being (valid comes from the French for truth)—to have the deepest part of ourselves recognized, there is something sacramental in that whether or not you’re a person of religion. There’s something saving in it whether or not you’re a person of religion. It brings you into the possibility of thinking: “There’s agency here.”

Pádraig: Well, I think that language used well becomes its own scripture. And we’re in need of all kinds of new scriptures. In poetry, there is an attempt to create a scripture that’s sufficient for the moment. But for the poet, and for anybody that’s reading that poet’s work, there is a recognition to say, “These words haven’t been put in the right way for me yet, so therefore I’m going to do it myself, or I’m going to read around to see who has done it.” And that that can bless the human experience and also create the human experience. By feeling created and validated, to be made—to be truthed into being (valid comes from the French for truth)—to have the deepest part of ourselves recognized, there is something sacramental in that whether or not you’re a person of religion. There’s something saving in it whether or not you’re a person of religion. It brings you into the possibility of thinking: “There’s agency here.” The temptation to read Piglia’s books as straightforward journals—despite the author’s insistence on treating them as fiction—can occasionally be maddening, as if their readers have been unwittingly enlisted in a postmodern game. And indeed we have, though much more is at stake. As Piglia witnessed the dissolution of Argentine society under a series of repressive governments, he sought new models of writing and representing reality. In metafiction, he found a means to subvert the conformity and censorship that flourished under these regimes. While he rejected the idea that fictional “coding” was possible only when living and writing under a restrictive government, he believed, as he told an interviewer, that “political contexts define ways of reading.” Through indirection and other literary techniques, Piglia revealed the frightening mechanisms of state power that had subjugated Argentina and the ways in which they might be resisted.

The temptation to read Piglia’s books as straightforward journals—despite the author’s insistence on treating them as fiction—can occasionally be maddening, as if their readers have been unwittingly enlisted in a postmodern game. And indeed we have, though much more is at stake. As Piglia witnessed the dissolution of Argentine society under a series of repressive governments, he sought new models of writing and representing reality. In metafiction, he found a means to subvert the conformity and censorship that flourished under these regimes. While he rejected the idea that fictional “coding” was possible only when living and writing under a restrictive government, he believed, as he told an interviewer, that “political contexts define ways of reading.” Through indirection and other literary techniques, Piglia revealed the frightening mechanisms of state power that had subjugated Argentina and the ways in which they might be resisted. Unlike much that was extracted from India, these paintings were not plunder, and those who created them were properly remunerated and often received due credit for their work. When annotating the paintings of birds and animals she commissioned, Lady Impey, wife of the chief justice of the Supreme Court in Calcutta, left a space for the artists’ names to be inscribed in Persian. Similarly, the outstanding studies of animals commissioned between 1795 and 1818 by the surgeon Francis Buchanan bear the inscription ‘Haludar Pinxt’, which means that this Bengali artist became known in Europe during his lifetime. Indeed, his image of an Indian Sambar deer, sent to the Company’s library in Leadenhall Street in 1808, was cited at the time in French and German scientific journals precisely because it had been ‘painted on the spot’ and provided the first accurate record of the animal’s appearance. It was also, like many of these paintings, a work of art in its own right, a perfect example of the fruitful confluence of European science and Indian sensibility.

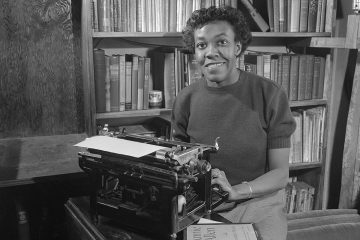

Unlike much that was extracted from India, these paintings were not plunder, and those who created them were properly remunerated and often received due credit for their work. When annotating the paintings of birds and animals she commissioned, Lady Impey, wife of the chief justice of the Supreme Court in Calcutta, left a space for the artists’ names to be inscribed in Persian. Similarly, the outstanding studies of animals commissioned between 1795 and 1818 by the surgeon Francis Buchanan bear the inscription ‘Haludar Pinxt’, which means that this Bengali artist became known in Europe during his lifetime. Indeed, his image of an Indian Sambar deer, sent to the Company’s library in Leadenhall Street in 1808, was cited at the time in French and German scientific journals precisely because it had been ‘painted on the spot’ and provided the first accurate record of the animal’s appearance. It was also, like many of these paintings, a work of art in its own right, a perfect example of the fruitful confluence of European science and Indian sensibility. The opening lines of Gwendolyn Brooks’s epic “The Anniad” are, like the rest of the poem, deceptively uncomplicated. “Think of sweet and chocolate,” she writes:

The opening lines of Gwendolyn Brooks’s epic “The Anniad” are, like the rest of the poem, deceptively uncomplicated. “Think of sweet and chocolate,” she writes: As I write this, Sydney, the city where I’ve set my life and much of my fiction over the past 27 years, is ringed by fire and choked by smoke. A combination fan and air purifier hums in the corner of my study. Seretide and Ventolin inhalers sit within reach on my desk. I’m surrounded by a lifetime’s accumulation of books, including some relatively rare and specialist volumes on China, in English and Chinese. This library might not be precious in monetary terms, but it’s priceless to me and vital to my work. I wonder which books I would save if I had to pack a car quickly and go. The thought of people making those decisions right now, including people I know, twists my gut.

As I write this, Sydney, the city where I’ve set my life and much of my fiction over the past 27 years, is ringed by fire and choked by smoke. A combination fan and air purifier hums in the corner of my study. Seretide and Ventolin inhalers sit within reach on my desk. I’m surrounded by a lifetime’s accumulation of books, including some relatively rare and specialist volumes on China, in English and Chinese. This library might not be precious in monetary terms, but it’s priceless to me and vital to my work. I wonder which books I would save if I had to pack a car quickly and go. The thought of people making those decisions right now, including people I know, twists my gut. It’s hard to make decisions that will change your life. It’s even harder to make a decision if you know that the outcome could change who you are. Our preferences are determined by who we are, and they might be quite different after a decision is made — and there’s no rational way of taking that into account. Philosopher L.A. Paul has been investigating these transformative experiences — from getting married, to having a child, to going to graduate school — with an eye to deciding how to live in the face of such choices. Of course we can ask people who have made such a choice what they think, but that doesn’t tell us whether the choice is a good one from the standpoint of our current selves, those who haven’t taken the plunge. We talk about what this philosophical conundrum means for real-world decisions, attitudes towards religious faith, and the tricky issue of what it means to be authentic to yourself when your “self” keeps changing over time.

It’s hard to make decisions that will change your life. It’s even harder to make a decision if you know that the outcome could change who you are. Our preferences are determined by who we are, and they might be quite different after a decision is made — and there’s no rational way of taking that into account. Philosopher L.A. Paul has been investigating these transformative experiences — from getting married, to having a child, to going to graduate school — with an eye to deciding how to live in the face of such choices. Of course we can ask people who have made such a choice what they think, but that doesn’t tell us whether the choice is a good one from the standpoint of our current selves, those who haven’t taken the plunge. We talk about what this philosophical conundrum means for real-world decisions, attitudes towards religious faith, and the tricky issue of what it means to be authentic to yourself when your “self” keeps changing over time. To walk from south to north on the peripatos, the path encircling the Acropolis of Athens – as I did one golden morning in December last year – takes you past the boisterous crowds swarming the stone seats of the Theatre of Dionysus. The path then threads just below the partially restored colonnades of the monumental Propylaea, which was thronged that morning with visitors pausing to chat and take photographs before they clambered past that monumental gateway up to the Parthenon. Proceed further along the curved trail and, like an epiphany, you will find yourself in the wilder north-facing precincts of that ancient outcrop. In the section known as the Long Rocks there are a series of alcoves of varying sizes, named ingloriously by the archaeologists as caves A, B, C and D. In its unanticipated tranquility, this stretch of rock still seems to host the older gods.

To walk from south to north on the peripatos, the path encircling the Acropolis of Athens – as I did one golden morning in December last year – takes you past the boisterous crowds swarming the stone seats of the Theatre of Dionysus. The path then threads just below the partially restored colonnades of the monumental Propylaea, which was thronged that morning with visitors pausing to chat and take photographs before they clambered past that monumental gateway up to the Parthenon. Proceed further along the curved trail and, like an epiphany, you will find yourself in the wilder north-facing precincts of that ancient outcrop. In the section known as the Long Rocks there are a series of alcoves of varying sizes, named ingloriously by the archaeologists as caves A, B, C and D. In its unanticipated tranquility, this stretch of rock still seems to host the older gods.