Danielle Charette talks to Thomas Piketty in Tocqueville 21:

Danielle Charette talks to Thomas Piketty in Tocqueville 21:

Danielle Charette: Capital and Ideology is clearly an ambitious book. It undertakes a history of what you call “inequality regimes” across many eras and in many different regions of the world. To tell the story you go well beyond traditional economics and venture into the fields of political science, history, sociology, and sometimes even literature and film. Of course, any interdisciplinary project comes with risks, since it requires commenting on fields in which you yourself may not be an expert. Can you say a bit why, as an economist, you organized Capital and Ideology in this interdisciplinary way?

Thomas Piketty: First of all, let me make clear that I don’t have a strong identity as an economist. I view my work more as the work of a social scientist, at the frontier between economic history, social history, historical economics, and political economy, or however you want to phrase it. I have written three books: Top Incomes in France in the Twentieth Century in 2001, then Capital in the Twenty-First Century in 2013, and now Capital and Ideology in 2019. Basically everything I have done over these past twenty years has been about the history of inequality. No book is exclusively about economics.

Now, that being said, you’re right that this new book is even more a book of social sciences than the previous two. My study of ideology sometimes takes the direction of anthropology or political science. I felt that this was necessary in order to better understand the evolution of inequality regimes. In the end, my main takeaway—as I say in the introduction of the book—is that the origins of inequality are more political and ideological than economic, technological, or even cultural.

More here.

A truly literary history eludes most working historians. Their books are too often weighed down by specialist jargon, and they know that neglecting scholarly trappings—extensive footnotes, name-checking fellow historians—means risking professional irrelevance. It is nearly impossible to reach that most coveted literary destination: a serious argument delivered with a light touch.

A truly literary history eludes most working historians. Their books are too often weighed down by specialist jargon, and they know that neglecting scholarly trappings—extensive footnotes, name-checking fellow historians—means risking professional irrelevance. It is nearly impossible to reach that most coveted literary destination: a serious argument delivered with a light touch.

A YEAR BEFORE ANNA KAVAN WAS FOUND DEAD

A YEAR BEFORE ANNA KAVAN WAS FOUND DEAD There are many arguments for theism, most of them not worth rehearsing. The ontological argument, first formulated by St Anselm in the 11th century and reframed by the 17th-century French rationalist René Descartes (1596-1650), maintains that God must exist because humans have an idea of a perfect being and existence is necessary to perfection. Since many of us have no such idea, it is a feeble gambit. The arguments of creationists are feebler, since they involve concocting a theory of intelligent design to fill gaps in science that the growth of knowledge may one day close. The idea of God is not a pseudo-scientific speculation.

There are many arguments for theism, most of them not worth rehearsing. The ontological argument, first formulated by St Anselm in the 11th century and reframed by the 17th-century French rationalist René Descartes (1596-1650), maintains that God must exist because humans have an idea of a perfect being and existence is necessary to perfection. Since many of us have no such idea, it is a feeble gambit. The arguments of creationists are feebler, since they involve concocting a theory of intelligent design to fill gaps in science that the growth of knowledge may one day close. The idea of God is not a pseudo-scientific speculation. Are humans the only animals that caucus? As the early 2020 presidential election season suggests, there are probably more natural and efficient ways to make a group choice. But we’re certainly not the only animals on Earth that vote. We’re not even the only primates that primary. Any animal living in a group needs to make decisions as a group, too. Even when they don’t agree with their companions, animals rely on one another for protection or help finding food. So they have to find ways to reach consensus about what the group should do next, or where it should live. While they may not conduct continent-spanning electoral contests like this coming Super Tuesday, species ranging from primates all the way to insects have methods for finding agreement that are surprisingly democratic. As meerkats start each day, they emerge from their burrows into the sunlight, then begin searching for food. Each meerkat forages for itself, digging in the dirt for bugs and other morsels, but they travel in loose groups, each animal up to about 30 feet from its neighbors, says Marta Manser, an animal-behavior scientist at the University of Zurich in Switzerland. Nonetheless, the meerkats move as one unit, drifting across the desert while they search and munch.

Are humans the only animals that caucus? As the early 2020 presidential election season suggests, there are probably more natural and efficient ways to make a group choice. But we’re certainly not the only animals on Earth that vote. We’re not even the only primates that primary. Any animal living in a group needs to make decisions as a group, too. Even when they don’t agree with their companions, animals rely on one another for protection or help finding food. So they have to find ways to reach consensus about what the group should do next, or where it should live. While they may not conduct continent-spanning electoral contests like this coming Super Tuesday, species ranging from primates all the way to insects have methods for finding agreement that are surprisingly democratic. As meerkats start each day, they emerge from their burrows into the sunlight, then begin searching for food. Each meerkat forages for itself, digging in the dirt for bugs and other morsels, but they travel in loose groups, each animal up to about 30 feet from its neighbors, says Marta Manser, an animal-behavior scientist at the University of Zurich in Switzerland. Nonetheless, the meerkats move as one unit, drifting across the desert while they search and munch. Greta’s father, Svante, and I are what is known in Sweden as “cultural workers” – trained in opera, music and theatre with half a career of work in those fields behind us. When I was pregnant with Greta, and working in Germany, Svante was acting at three different theatres in Sweden simultaneously. I had several years of binding contracts ahead of me at various opera houses all over Europe. With 1,000km between us, we talked over the phone about how we could get our new reality to work.

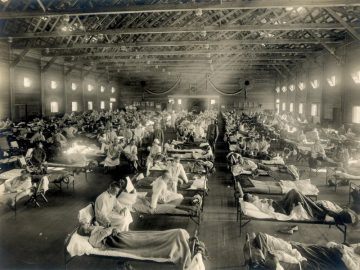

Greta’s father, Svante, and I are what is known in Sweden as “cultural workers” – trained in opera, music and theatre with half a career of work in those fields behind us. When I was pregnant with Greta, and working in Germany, Svante was acting at three different theatres in Sweden simultaneously. I had several years of binding contracts ahead of me at various opera houses all over Europe. With 1,000km between us, we talked over the phone about how we could get our new reality to work. Haskell County, Kansas, lies in the southwest corner of the state, near Oklahoma and Colorado. In 1918 sod houses were still common, barely distinguishable from the treeless, dry prairie they were dug out of. It had been cattle country—a now bankrupt ranch once handled 30,000 head—but Haskell farmers also raised hogs, which is one possible clue to the origin of the crisis that would terrorize the world that year. Another clue is that the county sits on a major migratory flyway for 17 bird species, including sand hill cranes and mallards. Scientists today understand that bird influenza viruses, like human influenza viruses, can also infect hogs, and when a bird virus and a human virus infect the same pig cell, their different genes can be shuffled and exchanged like playing cards, resulting in a new, perhaps especially lethal, virus.

Haskell County, Kansas, lies in the southwest corner of the state, near Oklahoma and Colorado. In 1918 sod houses were still common, barely distinguishable from the treeless, dry prairie they were dug out of. It had been cattle country—a now bankrupt ranch once handled 30,000 head—but Haskell farmers also raised hogs, which is one possible clue to the origin of the crisis that would terrorize the world that year. Another clue is that the county sits on a major migratory flyway for 17 bird species, including sand hill cranes and mallards. Scientists today understand that bird influenza viruses, like human influenza viruses, can also infect hogs, and when a bird virus and a human virus infect the same pig cell, their different genes can be shuffled and exchanged like playing cards, resulting in a new, perhaps especially lethal, virus. For John Morgan, an American expat living in Budapest, controlling the form the world takes comes down to shaping how white people dream.

For John Morgan, an American expat living in Budapest, controlling the form the world takes comes down to shaping how white people dream.

Dr. John Haygarth knew that there was something suspicious about Perkins’s Metallic Tractors. He’d heard all the theories about the newly patented medical device—about the way flesh reacted to metal, about noxious electrical fluids being expelled from the body. He’d heard that people plagued by rheumatism, pleurisy, and toothache swore the instrument offered them miraculous relief. Even George Washington was said to own a set. But Haygarth, a physician who had pioneered a method of preventing smallpox, sensed a sham. He set out to find the evidence. The year was 1799, and the Perkins tractors were already an international phenomenon. The device consisted of a pair of metallic rods—rounded on one end and tapering, at the other, to a point. Its inventor, Elisha Perkins, insisted that gently stroking each tractor over the affected area in alternation would draw off the electricity and provide relief. Thousands of sets were sold, for twenty-five dollars each. People were even said to have auctioned off their horses just to get hold of a pair. And, in an era when your alternatives might be bloodletting, leeches, and purging, you could see the appeal.

Dr. John Haygarth knew that there was something suspicious about Perkins’s Metallic Tractors. He’d heard all the theories about the newly patented medical device—about the way flesh reacted to metal, about noxious electrical fluids being expelled from the body. He’d heard that people plagued by rheumatism, pleurisy, and toothache swore the instrument offered them miraculous relief. Even George Washington was said to own a set. But Haygarth, a physician who had pioneered a method of preventing smallpox, sensed a sham. He set out to find the evidence. The year was 1799, and the Perkins tractors were already an international phenomenon. The device consisted of a pair of metallic rods—rounded on one end and tapering, at the other, to a point. Its inventor, Elisha Perkins, insisted that gently stroking each tractor over the affected area in alternation would draw off the electricity and provide relief. Thousands of sets were sold, for twenty-five dollars each. People were even said to have auctioned off their horses just to get hold of a pair. And, in an era when your alternatives might be bloodletting, leeches, and purging, you could see the appeal. Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, the 18th-century poet and philosopher, believed life was hardwired with archetypes, or models, which instructed its development. Yet he was fascinated with how life could, at the same time, be so malleable. One day, while meditating on a leaf, the poet had what you might call a proto-evolutionary thought: Plants were never created “and then locked into the given form” but have instead been given, he later wrote, a “felicitous mobility and plasticity that allows them to grow and adapt themselves to many different conditions in many different places.” A rediscovery of principles of genetic inheritance in the early 20th century showed that organisms could not learn or acquire heritable traits by interacting with their environment, but they did not yet explain how life could undergo such shapeshifting tricks—the plasticity that fascinated Goethe.

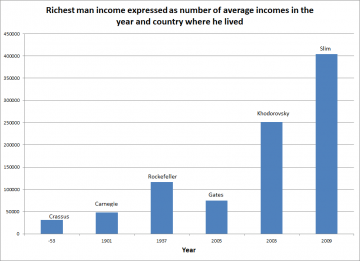

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, the 18th-century poet and philosopher, believed life was hardwired with archetypes, or models, which instructed its development. Yet he was fascinated with how life could, at the same time, be so malleable. One day, while meditating on a leaf, the poet had what you might call a proto-evolutionary thought: Plants were never created “and then locked into the given form” but have instead been given, he later wrote, a “felicitous mobility and plasticity that allows them to grow and adapt themselves to many different conditions in many different places.” A rediscovery of principles of genetic inheritance in the early 20th century showed that organisms could not learn or acquire heritable traits by interacting with their environment, but they did not yet explain how life could undergo such shapeshifting tricks—the plasticity that fascinated Goethe. Branko Milanovic over at his website:

Branko Milanovic over at his website: Katherine Angel over at the Verso Blog:

Katherine Angel over at the Verso Blog: Danielle Charette talks to Thomas Piketty in Tocqueville 21:

Danielle Charette talks to Thomas Piketty in Tocqueville 21: Joel Mokyr in Aeon:

Joel Mokyr in Aeon: