Eva Botkin-Kowacki in The Christian Science Monitor:

To some witnesses, it simply didn’t make sense. “This is really an irrational phenomenon,” wrote the Polish historian Emanuel Ringelblum, in notes found after his execution by the Gestapo. “There’s no explaining it rationally.” It was November 1941 in the Warsaw Ghetto, the sliver of Poland’s capital that the Nazi occupying government had transformed into a squalid holding pen for the area’s Jews, Romani, and others deemed undesirable. Typhus had raged through the community all through the summer and early autumn. But then, just as infection rates were expected to have skyrocketed as winter approached, cases fell dramatically. “I heard this from the apothecaries, and the same thing from doctors and the hospital,” Ringelblum wrote that month. “The epidemic rate has fallen some 40 per cent.”

To some witnesses, it simply didn’t make sense. “This is really an irrational phenomenon,” wrote the Polish historian Emanuel Ringelblum, in notes found after his execution by the Gestapo. “There’s no explaining it rationally.” It was November 1941 in the Warsaw Ghetto, the sliver of Poland’s capital that the Nazi occupying government had transformed into a squalid holding pen for the area’s Jews, Romani, and others deemed undesirable. Typhus had raged through the community all through the summer and early autumn. But then, just as infection rates were expected to have skyrocketed as winter approached, cases fell dramatically. “I heard this from the apothecaries, and the same thing from doctors and the hospital,” Ringelblum wrote that month. “The epidemic rate has fallen some 40 per cent.”

The Warsaw Ghetto should have been an optimal site for an outbreak. More than 450,000 mostly Jewish inmates were crammed into 1.3 square miles, making for a population density between 5 and 10 times that of today’s busiest cities. Nazi authorities deliberately kept resources from entering the area, all the while using fear of disease in anti-Semitic party propaganda. Nevertheless, typhus rates in the Warsaw Ghetto were plummeting.

The only explanation, according to research published today in the journal Science Advances, is that the inmates did it themselves, by sheltering in place, promoting and enforcing hygiene, and practicing social distancing. This remarkable story of an oppressed community rallying together to combat a public health crisis holds obvious implications for today, as the novel coronavirus pandemic continues to claim thousands of lives around the world daily and debilitate national economies. “It’s one of the great medical stories of all time,” says Howard Markel, the University of Michigan physician and medical historian who coined the term “flatten the curve” in relation to COVID-19. “We should take heart and inspiration from the courage, bravery, and unity of doctors, nurses, and patients alike to combat an infectious foe. We need to do that today, and they did it under much more dire circumstances.”

More here.

“The Plague” did not come easily to Camus. He wrote it in Oran, during World War II, when he was living in an apartment borrowed from in-laws he disliked, and then in wartime France, tubercular and alone, separated from his wife after missing the last boat back to Algeria. Unlike the shorter, harsher sentences of “The Stranger,” which Sartre quipped could have been titled “Translated From Silence,” the sentences of “The Plague” bear witness to the tension and monotony of illness and quarantine: They stretch their lengths to match the pull of anxious waiting. By the time the book was published in 1947, writers were looking for a way to bear witness as well to the Nazi occupation of France, and “The Plague” was championed as the novel of the occupation and the Resistance. For Camus, illness was both his lived experience and a metaphor for war, the creep of fascism, the horror of Vichy France collaborating in mass murder.

“The Plague” did not come easily to Camus. He wrote it in Oran, during World War II, when he was living in an apartment borrowed from in-laws he disliked, and then in wartime France, tubercular and alone, separated from his wife after missing the last boat back to Algeria. Unlike the shorter, harsher sentences of “The Stranger,” which Sartre quipped could have been titled “Translated From Silence,” the sentences of “The Plague” bear witness to the tension and monotony of illness and quarantine: They stretch their lengths to match the pull of anxious waiting. By the time the book was published in 1947, writers were looking for a way to bear witness as well to the Nazi occupation of France, and “The Plague” was championed as the novel of the occupation and the Resistance. For Camus, illness was both his lived experience and a metaphor for war, the creep of fascism, the horror of Vichy France collaborating in mass murder. Servaas Storm over at INET (with comments by Joseph Halevi and Peter Kriesler, Duncan Foley, and Thomas Ferguson

Servaas Storm over at INET (with comments by Joseph Halevi and Peter Kriesler, Duncan Foley, and Thomas Ferguson  Adam Tooze in Foreign Policy:

Adam Tooze in Foreign Policy: Andrew Whitehead in The Wire:

Andrew Whitehead in The Wire: Astra Taylor talks to Rutgers faculty union president Todd Wolfson, over at Boston Review:

Astra Taylor talks to Rutgers faculty union president Todd Wolfson, over at Boston Review: The Immanent Frame has

The Immanent Frame has  Hot Springs, as David Hill writes in “The Vapors,” a history of the town during its sin-soaked heyday, let a lot of people be — with varying degrees of vengeance. Among them were workaday gamblers and good-timers like Kelley, but also bookmakers, con artists, prostitutes, shills, crooked auctioneers, outlandishly corrupt politicians and boldface-named mobsters. From about 1870 until 1967, when the reformist governor Winthrop Rockefeller shut off the vice spigot, the town’s chief municipal expression was a wink. The mayors winked. The cops winked. The preachers winked, or at least averted their gaze. Winking was how a Bible Belt town of 28,000 (circa 1960) attracted upward of five million visitors per year and why, as Hill writes, on any given Saturday night, there may have been “no more exhilarating place to be in the entire country.”

Hot Springs, as David Hill writes in “The Vapors,” a history of the town during its sin-soaked heyday, let a lot of people be — with varying degrees of vengeance. Among them were workaday gamblers and good-timers like Kelley, but also bookmakers, con artists, prostitutes, shills, crooked auctioneers, outlandishly corrupt politicians and boldface-named mobsters. From about 1870 until 1967, when the reformist governor Winthrop Rockefeller shut off the vice spigot, the town’s chief municipal expression was a wink. The mayors winked. The cops winked. The preachers winked, or at least averted their gaze. Winking was how a Bible Belt town of 28,000 (circa 1960) attracted upward of five million visitors per year and why, as Hill writes, on any given Saturday night, there may have been “no more exhilarating place to be in the entire country.” In her 1999 book Hiroshima Traces, the anthropologist Lisa Yoneyama describes the hibakusha’s intense relationship with the dead differently from Lifton’s ‘death in life’. Yoneyama sees the hibakusha as giving the bomb’s victims life after death. She writes that the hibakusha have developed ‘testimonial practices’ that can be compared to ‘a shamanistic ritual that summons dead souls’, to ‘resurrect the deceased and endow them with voices’.

In her 1999 book Hiroshima Traces, the anthropologist Lisa Yoneyama describes the hibakusha’s intense relationship with the dead differently from Lifton’s ‘death in life’. Yoneyama sees the hibakusha as giving the bomb’s victims life after death. She writes that the hibakusha have developed ‘testimonial practices’ that can be compared to ‘a shamanistic ritual that summons dead souls’, to ‘resurrect the deceased and endow them with voices’. Space, as they say, is big. In The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy (1979), Douglas Adams elaborates: ‘You may think it’s a long way down the road to the chemist, but that’s just peanuts to space.’ It’s hard to convey in everyday terms the enormity of the cosmos when most of us have trouble even visualising the size of the Earth, much less the galaxy, or the vast expanses of intergalactic space. We often talk in terms of light-years – the distance light can travel in a year – as though the speed of light is somehow more intuitive than a number written in the trillions of kilometres. We give benchmarks in the same terms (it takes light 1.3 seconds to travel between the Earth and the Moon) but, in our everyday experience, light is instantaneous. We might as well talk about the height of a building in terms of stacking up atoms.

Space, as they say, is big. In The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy (1979), Douglas Adams elaborates: ‘You may think it’s a long way down the road to the chemist, but that’s just peanuts to space.’ It’s hard to convey in everyday terms the enormity of the cosmos when most of us have trouble even visualising the size of the Earth, much less the galaxy, or the vast expanses of intergalactic space. We often talk in terms of light-years – the distance light can travel in a year – as though the speed of light is somehow more intuitive than a number written in the trillions of kilometres. We give benchmarks in the same terms (it takes light 1.3 seconds to travel between the Earth and the Moon) but, in our everyday experience, light is instantaneous. We might as well talk about the height of a building in terms of stacking up atoms.

As in a fairy tale, the cities, to defend themselves from an invisible yet powerful enemy, have disappeared: they have gone into exile. They have declared themselves banned, outlawed, and now they lie before us like inside an archaeological museum or a diorama.

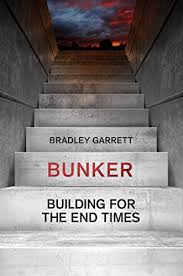

As in a fairy tale, the cities, to defend themselves from an invisible yet powerful enemy, have disappeared: they have gone into exile. They have declared themselves banned, outlawed, and now they lie before us like inside an archaeological museum or a diorama. But the word ‘bunker’ also has the scent of modernity about it. As Bradley Garrett explains in his book, it was a corollary of the rise of air power, as a result of which the battlefield became three-dimensional. With the enemy above and equipped with high explosives, you had to dig down and protect yourself with metres of concrete. Garrett’s previous book, Explore Everything, was a fascinating insider’s look at illicit ‘urban exploration’, and he kicks off Bunker with an account of time spent poking around the Burlington Bunker, which would have been used by the UK government in the event of a nuclear war. The Cold War may have ended, but governments still build bunkers, as Garrett shows: Chinese contractors have recently completed a 23,000-square-metre complex in Djibouti. But these grand, often secret manifestations of official fear are not the main focus of the book. Instead, Garrett is interested in private bunkers and the people who build them, people like Robert Vicino, founder of the Vivos Group, who purchased the Burlington Bunker with the intent of making a worldwide chain of apocalypse retreats.

But the word ‘bunker’ also has the scent of modernity about it. As Bradley Garrett explains in his book, it was a corollary of the rise of air power, as a result of which the battlefield became three-dimensional. With the enemy above and equipped with high explosives, you had to dig down and protect yourself with metres of concrete. Garrett’s previous book, Explore Everything, was a fascinating insider’s look at illicit ‘urban exploration’, and he kicks off Bunker with an account of time spent poking around the Burlington Bunker, which would have been used by the UK government in the event of a nuclear war. The Cold War may have ended, but governments still build bunkers, as Garrett shows: Chinese contractors have recently completed a 23,000-square-metre complex in Djibouti. But these grand, often secret manifestations of official fear are not the main focus of the book. Instead, Garrett is interested in private bunkers and the people who build them, people like Robert Vicino, founder of the Vivos Group, who purchased the Burlington Bunker with the intent of making a worldwide chain of apocalypse retreats. “The Well” is distinctive in the sheer fact of its characterizations and dramatizations—it depicts, alongside its white characters, a wide variety of Black characters in a wide range of settings (work, school, home, government offices, street life), speaking substantially (if briefly) about the trouble at hand and their views of it. From the start, the movie dispels all ambiguity: Carolyn, who loved flowers, walks through an empty field on the way to school and falls into a long-abandoned well. Her teacher, a white woman, reports her absence to Carolyn’s mother, Martha (Maidie Norman), who informs the town’s sheriff, Ben Kellog (Richard Rober), a white man. Despite the frank assertion of Carolyn’s uncle, Gaines (Alfred Grant), that the police won’t be looking very hard for a Black child, Ben sharply declares and clearly displays his authentic concern, energetically and devotedly sending more or less the entire police force—all white men—to scour the town for Carolyn.

“The Well” is distinctive in the sheer fact of its characterizations and dramatizations—it depicts, alongside its white characters, a wide variety of Black characters in a wide range of settings (work, school, home, government offices, street life), speaking substantially (if briefly) about the trouble at hand and their views of it. From the start, the movie dispels all ambiguity: Carolyn, who loved flowers, walks through an empty field on the way to school and falls into a long-abandoned well. Her teacher, a white woman, reports her absence to Carolyn’s mother, Martha (Maidie Norman), who informs the town’s sheriff, Ben Kellog (Richard Rober), a white man. Despite the frank assertion of Carolyn’s uncle, Gaines (Alfred Grant), that the police won’t be looking very hard for a Black child, Ben sharply declares and clearly displays his authentic concern, energetically and devotedly sending more or less the entire police force—all white men—to scour the town for Carolyn.