Sydney Perkowitz in Nautilus:

In January, Robert Williams, an African-American man, was wrongfully arrested due to an inaccurate facial recognition algorithm, a computerized approach that analyzes human faces and identifies them by comparison to database images of known people. He was handcuffed and arrested in front of his family by Detroit police without being told why, then jailed overnight after the police took mugshots, fingerprints, and a DNA sample. The next day, detectives showed Williams a surveillance video image of an African-American man standing in a store that sells watches. It immediately became clear that he was not Williams. Detailing his arrest in the Washington Post, Williams wrote, “The cops looked at each other. I heard one say that ‘the computer must have gotten it wrong.’” Williams learned that in investigating a theft from the store, a facial recognition system had tagged his driver’s license photo as matching the surveillance image. But the next steps, where investigators first confirm the match, then seek more evidence for an arrest, were poorly done and Williams was brought in. He had to spend 30 hours in jail and post a $1,000 bond before he was freed.

In January, Robert Williams, an African-American man, was wrongfully arrested due to an inaccurate facial recognition algorithm, a computerized approach that analyzes human faces and identifies them by comparison to database images of known people. He was handcuffed and arrested in front of his family by Detroit police without being told why, then jailed overnight after the police took mugshots, fingerprints, and a DNA sample. The next day, detectives showed Williams a surveillance video image of an African-American man standing in a store that sells watches. It immediately became clear that he was not Williams. Detailing his arrest in the Washington Post, Williams wrote, “The cops looked at each other. I heard one say that ‘the computer must have gotten it wrong.’” Williams learned that in investigating a theft from the store, a facial recognition system had tagged his driver’s license photo as matching the surveillance image. But the next steps, where investigators first confirm the match, then seek more evidence for an arrest, were poorly done and Williams was brought in. He had to spend 30 hours in jail and post a $1,000 bond before he was freed.

What makes the Williams arrest unique is that it received public attention, reports the American Civil Liberties Union.1 With over 4,000 police departments using facial recognition, it is virtually certain that other people have been wrongly implicated in crimes. In 2019, Amara Majeed, a Brown University student, was falsely identified by facial recognition as a suspect in a terrorist bombing in Sri Lanka. Sri Lankan police retracted the mistake, but not before Majeed received death threats. Even if a person goes free, his or her personal data remains listed among criminal records unless special steps are taken to expunge it.

More here.

Democracy imposes a substantial moral burden on citizens. They must regard one another as political equals, even when they disagree deeply about justice. Each side is likely to see the opposition as not only wrong about the issue, but on the side of injustice. How can citizens both stand up for justice and yet embrace a political arrangement that gives injustice an equal say? Political sympathy, a disposition to recognize in our opposition an attempt to live according to their conception of value, is proposed as a way to lighten democracy’s burden.

Democracy imposes a substantial moral burden on citizens. They must regard one another as political equals, even when they disagree deeply about justice. Each side is likely to see the opposition as not only wrong about the issue, but on the side of injustice. How can citizens both stand up for justice and yet embrace a political arrangement that gives injustice an equal say? Political sympathy, a disposition to recognize in our opposition an attempt to live according to their conception of value, is proposed as a way to lighten democracy’s burden. Human civilization is only a few thousand years old (depending on how we count). So if civilization will ultimately last for millions of years, it could be considered surprising that we’ve found ourselves so early in history. Should we therefore predict that human civilization will probably disappear within a few thousand years? This “Doomsday Argument” shares a family resemblance to ideas used by many professional cosmologists to judge whether a model of the universe is natural or not. Philosopher Nick Bostrom is the world’s expert on these kinds of anthropic arguments. We talk through them, leading to the biggest doozy of them all: the idea that our perceived reality might be a computer simulation being run by enormously more powerful beings.

Human civilization is only a few thousand years old (depending on how we count). So if civilization will ultimately last for millions of years, it could be considered surprising that we’ve found ourselves so early in history. Should we therefore predict that human civilization will probably disappear within a few thousand years? This “Doomsday Argument” shares a family resemblance to ideas used by many professional cosmologists to judge whether a model of the universe is natural or not. Philosopher Nick Bostrom is the world’s expert on these kinds of anthropic arguments. We talk through them, leading to the biggest doozy of them all: the idea that our perceived reality might be a computer simulation being run by enormously more powerful beings. “One way the internet distorts our picture of ourselves is by feeding the human tendency to overestimate our knowledge of how the world works,”

“One way the internet distorts our picture of ourselves is by feeding the human tendency to overestimate our knowledge of how the world works,”  At it

At it

There’s a trope of the British Asian identity narrative, once captured with such originality and brilliance in Hanif Kureishi’s

There’s a trope of the British Asian identity narrative, once captured with such originality and brilliance in Hanif Kureishi’s  With the refinement and reduced cost of sequencing technology, science has reached another inflection point: population-scale genomics, where clinical-grade assays can be used to advance healthcare, while fueling research. The Healthy Nevada Project (HNP) epitomizes that movement. A population health initiative run by the Renown Institute for Health Innovation (Renown IHI), a partnership between Renown Health and the Desert Research Institute, the project aims to combine genomic, environmental and medical data from 250,000 participants to assess the influence of genetics on health and disease. The study also uses sequencing data to screen participants for medically actionable genetic conditions, such as familial hypercholesterolemia (FH), hereditary breast and ovarian cancer syndrome (HBOC), and Lynch syndrome (LS).

With the refinement and reduced cost of sequencing technology, science has reached another inflection point: population-scale genomics, where clinical-grade assays can be used to advance healthcare, while fueling research. The Healthy Nevada Project (HNP) epitomizes that movement. A population health initiative run by the Renown Institute for Health Innovation (Renown IHI), a partnership between Renown Health and the Desert Research Institute, the project aims to combine genomic, environmental and medical data from 250,000 participants to assess the influence of genetics on health and disease. The study also uses sequencing data to screen participants for medically actionable genetic conditions, such as familial hypercholesterolemia (FH), hereditary breast and ovarian cancer syndrome (HBOC), and Lynch syndrome (LS).

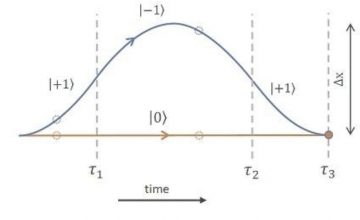

A group of theoretical physicists, including two physicists from the University of Groningen, have proposed a ‘table-top’ device that could measure gravity waves. However, their actual aim is to answer one of the biggest questions in physics: is gravity a quantum phenomenon? The key element for the device is the quantum superposition of large objects. Their design was published in New Journal of Physics on 6 August.

A group of theoretical physicists, including two physicists from the University of Groningen, have proposed a ‘table-top’ device that could measure gravity waves. However, their actual aim is to answer one of the biggest questions in physics: is gravity a quantum phenomenon? The key element for the device is the quantum superposition of large objects. Their design was published in New Journal of Physics on 6 August. Qelbinur Sedik has witnessed wanton cruelty, gratuitous violence, humiliation, torture, and death meted out to her people on an unimaginable scale — but has been forced to keep the crushing secret until now.

Qelbinur Sedik has witnessed wanton cruelty, gratuitous violence, humiliation, torture, and death meted out to her people on an unimaginable scale — but has been forced to keep the crushing secret until now.

TRISTRAM SHANDY sailed into eighteenth-century literary history alongside such bawdy picaresques as Tom Jones. But unlike the rest Laurence Sterne’s creation is an antinovel: It starts and stops, has entire pages that aren’t even text—blank or solid black or marbled or filled with lines and swirls that indicate the wayward shapes of the narrative (at such moments it seems like what Sterne really is is a concrete poet). On the occasions when the author doesn’t want you to know what naughty thing he’s saying (though he quit being a minister to write, Sterne was still a modest man) there are heaving piles of asterisks. By such means—explained in an insanely arch but persistently conversational manner—you get that the book in your hands is alive and it will turn any whimsical damn way he wants. Laurence Sterne is a funny guy and there is a devastating presentness to this work.

TRISTRAM SHANDY sailed into eighteenth-century literary history alongside such bawdy picaresques as Tom Jones. But unlike the rest Laurence Sterne’s creation is an antinovel: It starts and stops, has entire pages that aren’t even text—blank or solid black or marbled or filled with lines and swirls that indicate the wayward shapes of the narrative (at such moments it seems like what Sterne really is is a concrete poet). On the occasions when the author doesn’t want you to know what naughty thing he’s saying (though he quit being a minister to write, Sterne was still a modest man) there are heaving piles of asterisks. By such means—explained in an insanely arch but persistently conversational manner—you get that the book in your hands is alive and it will turn any whimsical damn way he wants. Laurence Sterne is a funny guy and there is a devastating presentness to this work. Every corpse is an ecosystem. Each fallen bird, landed fish, beached whale, decomposing log, plucked flower is destined to change from a conglomerate of giant molecules, the most complex system in the universe known, into clouds and drifts of much smaller organic molecules. The process of decay is driven by scavengers, in nature beginning with vultures and blowflies and ending with fungi and bacteria. What do ants do with their dead? In many species, if a colony member is badly injured in the field it is carried home and eaten. If injured only moderately, it may be allowed to live and heal. Most ant warriors that die in battle outside the nest never return. They instead fill the jaws and beaks of predators. An ant that dies from old age or disease inside the nest simply comes to a standstill or else falls to the side with her legs crumpled up. In most cases, she is allowed to stay in place. After, at most, a few days, a nest mate picks her up and carries her out of the nest or to a refuse pile in one of the chambers within the nest. In this cemetery chamber is also dumped miscellaneous refuse, including the inedible remains of prey. There is no ceremony. It occurred to me early in my studies of chemical communication in ants that the bodies of the dead are likely recognized by the odor of their decomposition. Of all the substances uniquely present in dead insects, one or more must be the signal that triggers corpse disposal by ants. If live ants demonstrably use such molecules to release other instinctive social behavior in the service of the colony, why not in death also?

Every corpse is an ecosystem. Each fallen bird, landed fish, beached whale, decomposing log, plucked flower is destined to change from a conglomerate of giant molecules, the most complex system in the universe known, into clouds and drifts of much smaller organic molecules. The process of decay is driven by scavengers, in nature beginning with vultures and blowflies and ending with fungi and bacteria. What do ants do with their dead? In many species, if a colony member is badly injured in the field it is carried home and eaten. If injured only moderately, it may be allowed to live and heal. Most ant warriors that die in battle outside the nest never return. They instead fill the jaws and beaks of predators. An ant that dies from old age or disease inside the nest simply comes to a standstill or else falls to the side with her legs crumpled up. In most cases, she is allowed to stay in place. After, at most, a few days, a nest mate picks her up and carries her out of the nest or to a refuse pile in one of the chambers within the nest. In this cemetery chamber is also dumped miscellaneous refuse, including the inedible remains of prey. There is no ceremony. It occurred to me early in my studies of chemical communication in ants that the bodies of the dead are likely recognized by the odor of their decomposition. Of all the substances uniquely present in dead insects, one or more must be the signal that triggers corpse disposal by ants. If live ants demonstrably use such molecules to release other instinctive social behavior in the service of the colony, why not in death also?