S. G. Belknap at The Point:

James never stopped short in an exploration or an argument—and for him that meant never stopping short of the biggest question: the religious one. His thinking of the late 1890s kept pushing in this direction, culminating in the Gifford Lectures delivered in Edinburgh in 1901 and 1902, the lectures known to posterity as The Varieties of Religious Experience. James felt that the question of this world and the other world was somehow decisive for all of us, whichever way we answered it. And that included a whole lot of answers for someone like William James—attender of séances, consulter of mediums and all-around junkie for experience. In “The Will to Believe,” James is mostly interested in leveling the playing field vis-à-vis his skeptical colleagues. When it comes down to it, he wonders, why can’t we just go ahead and will the belief in God? The stern-minded skeptic is happy to object: we have no evidence for it. James replies: we have no evidence against it. The skeptic concedes, and objects again: well, then, I’ll wait until we have decisive evidence one way or the other. William James: to spend a life in indecision is no different from choosing against it; for example, if you have no decisive evidence that a potential career is best for you, you can’t just delay your decision until you die. The skeptic: but religion is not like that. William James: why not?

James never stopped short in an exploration or an argument—and for him that meant never stopping short of the biggest question: the religious one. His thinking of the late 1890s kept pushing in this direction, culminating in the Gifford Lectures delivered in Edinburgh in 1901 and 1902, the lectures known to posterity as The Varieties of Religious Experience. James felt that the question of this world and the other world was somehow decisive for all of us, whichever way we answered it. And that included a whole lot of answers for someone like William James—attender of séances, consulter of mediums and all-around junkie for experience. In “The Will to Believe,” James is mostly interested in leveling the playing field vis-à-vis his skeptical colleagues. When it comes down to it, he wonders, why can’t we just go ahead and will the belief in God? The stern-minded skeptic is happy to object: we have no evidence for it. James replies: we have no evidence against it. The skeptic concedes, and objects again: well, then, I’ll wait until we have decisive evidence one way or the other. William James: to spend a life in indecision is no different from choosing against it; for example, if you have no decisive evidence that a potential career is best for you, you can’t just delay your decision until you die. The skeptic: but religion is not like that. William James: why not?

more here.

No one is going to base a claim for Bloom’s merits on this final book. But it does indicate, with painful acuity, that the critic may have had little understanding of how literature is made — which is not out of ideas, as Mallarmé patiently explained to Cézanne. It doesn’t achieve its effects by saying ‘this is funny’ or ‘this is so moving’. It relishes its own voice — and to dwell on what it has stolen from others misses its ambition.

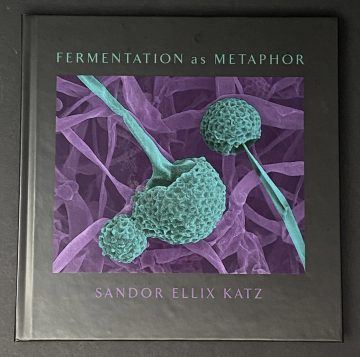

No one is going to base a claim for Bloom’s merits on this final book. But it does indicate, with painful acuity, that the critic may have had little understanding of how literature is made — which is not out of ideas, as Mallarmé patiently explained to Cézanne. It doesn’t achieve its effects by saying ‘this is funny’ or ‘this is so moving’. It relishes its own voice — and to dwell on what it has stolen from others misses its ambition. Sandor Katz: Well, sure. The reason I started calling myself a fermentation revivalist is from my sense of how common fermentation has been in the not too distant past and it’s so integral to all of our food traditions. Whatever part of the world our ancestors came from, fermentation is an essential part of how people make effective use of whatever food resources are available to them, but in the last several generations and at different paces in different parts of the world, people have become increasingly distanced from the production of food and all of the processes that we use to transform the raw products of agriculture into all of the foods that people eat and drink. And it so happens that the same time period where these processes became more mysterious and distanced to people is also the time when the war on bacteria developed. People developed this fear, projected all of their fear of bacteria onto these ancient and important transformative fermentation processes. So when I call myself a fermentation revivalist, it’s about demystifying the process of fermentation, getting people comfortable with it, and encouraging people to familiarize themselves with processes that are extremely important but have become mysterious for people.

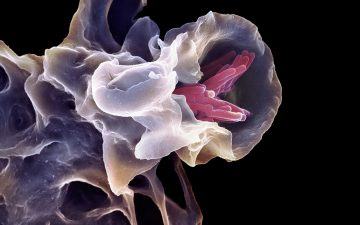

Sandor Katz: Well, sure. The reason I started calling myself a fermentation revivalist is from my sense of how common fermentation has been in the not too distant past and it’s so integral to all of our food traditions. Whatever part of the world our ancestors came from, fermentation is an essential part of how people make effective use of whatever food resources are available to them, but in the last several generations and at different paces in different parts of the world, people have become increasingly distanced from the production of food and all of the processes that we use to transform the raw products of agriculture into all of the foods that people eat and drink. And it so happens that the same time period where these processes became more mysterious and distanced to people is also the time when the war on bacteria developed. People developed this fear, projected all of their fear of bacteria onto these ancient and important transformative fermentation processes. So when I call myself a fermentation revivalist, it’s about demystifying the process of fermentation, getting people comfortable with it, and encouraging people to familiarize themselves with processes that are extremely important but have become mysterious for people. Animal immune systems depend on white blood cells called macrophages that devour and engulf invaders. The cells pursue with determination and gusto: under a microscope you can watch a blob-like macrophage chase a bacterium across the slide, switching course this way and that as its prey tries to escape through an obstacle course of red blood cells, before it finally catches the rogue microbe and gobbles it up.

Animal immune systems depend on white blood cells called macrophages that devour and engulf invaders. The cells pursue with determination and gusto: under a microscope you can watch a blob-like macrophage chase a bacterium across the slide, switching course this way and that as its prey tries to escape through an obstacle course of red blood cells, before it finally catches the rogue microbe and gobbles it up. The current debates over cancel culture are odd because few involved in them have been canceled, or risk being canceled, while entire institutions are indeed being canceled. Institutions that serve and amplify the interests of the working class, such as local newspapers, unions, and churches.

The current debates over cancel culture are odd because few involved in them have been canceled, or risk being canceled, while entire institutions are indeed being canceled. Institutions that serve and amplify the interests of the working class, such as local newspapers, unions, and churches. “There is only one school,” Amis has said, “that of talent.” Only the talented would ever think this, and only the supremely talented would ever say it out loud. Inside Story is subtitled How to Write. But Amis has been telling us how to write for half a century now, and not just in his criticism. The virtuoso is always also a pedagogue. Look – this is how you do it! And the feudal lord – the seigneur – is, by definition, an aristocrat (and, not incidentally, by definition male): “rangy, well-travelled, big-cocked”, in the mocking, but also not-quite-mocking, words of Charles Highway in The Rachel Papers (1973). When Amis fails, this seigneurialism is what he’s left with: all those epigrams! All those cringey jokes! That tone of sneering condescension! (See Yellow Dog, The Pregnant Widow, Lionel Asbo. Seigneurialism – anathematised as “male privilege” – is what feminist critics have tended to find so rebarbative in Amis’s work, and they’re not wrong.) When he succeeds, the seigneurialism is merely part of the effect (see Money, London Fields, Time’s Arrow, almost all of the nonfiction).

“There is only one school,” Amis has said, “that of talent.” Only the talented would ever think this, and only the supremely talented would ever say it out loud. Inside Story is subtitled How to Write. But Amis has been telling us how to write for half a century now, and not just in his criticism. The virtuoso is always also a pedagogue. Look – this is how you do it! And the feudal lord – the seigneur – is, by definition, an aristocrat (and, not incidentally, by definition male): “rangy, well-travelled, big-cocked”, in the mocking, but also not-quite-mocking, words of Charles Highway in The Rachel Papers (1973). When Amis fails, this seigneurialism is what he’s left with: all those epigrams! All those cringey jokes! That tone of sneering condescension! (See Yellow Dog, The Pregnant Widow, Lionel Asbo. Seigneurialism – anathematised as “male privilege” – is what feminist critics have tended to find so rebarbative in Amis’s work, and they’re not wrong.) When he succeeds, the seigneurialism is merely part of the effect (see Money, London Fields, Time’s Arrow, almost all of the nonfiction). The story of Joy Division, and later New Order, is repeated so often it feels more like myth than reality. Maxine Peake’s voice is full of whispered awe as she leads us through a story that begins with three simple words – “Band seeks singer” – and ends with the making of the iconic “Blue Monday”.

The story of Joy Division, and later New Order, is repeated so often it feels more like myth than reality. Maxine Peake’s voice is full of whispered awe as she leads us through a story that begins with three simple words – “Band seeks singer” – and ends with the making of the iconic “Blue Monday”. ISLAMABAD, Pakistan — I am angry. All the time. I’ve been angry for years. Ever since I began to grasp the staggering extent of violence — emotional, mental and physical — against women in Pakistan. Women here, all 100 million of us, exist in collective fury. “Every day, I am reminded of a reason I shouldn’t exist,” my 19-year-old friend recently told me in a cafe in Islamabad. When she gets into an Uber, she sits right behind the driver so that he can’t reach back and grab her. We agreed that we would jump out of a moving car if that ever happened. We debated whether pepper spray was better than a knife. When I step outside, I step into a country of men who stare. I could be making the short walk from my car to the bookstore or walking through the aisles at the supermarket. I could be wrapped in a shawl or behind two layers of face mask. But I will be followed by searing eyes, X-raying me. Because here, it is culturally acceptable for men to gape at women unblinkingly, as if we are all in a staring contest that nobody told half the population about, a contest hinged on a subtle form of psychological violence.

ISLAMABAD, Pakistan — I am angry. All the time. I’ve been angry for years. Ever since I began to grasp the staggering extent of violence — emotional, mental and physical — against women in Pakistan. Women here, all 100 million of us, exist in collective fury. “Every day, I am reminded of a reason I shouldn’t exist,” my 19-year-old friend recently told me in a cafe in Islamabad. When she gets into an Uber, she sits right behind the driver so that he can’t reach back and grab her. We agreed that we would jump out of a moving car if that ever happened. We debated whether pepper spray was better than a knife. When I step outside, I step into a country of men who stare. I could be making the short walk from my car to the bookstore or walking through the aisles at the supermarket. I could be wrapped in a shawl or behind two layers of face mask. But I will be followed by searing eyes, X-raying me. Because here, it is culturally acceptable for men to gape at women unblinkingly, as if we are all in a staring contest that nobody told half the population about, a contest hinged on a subtle form of psychological violence. Robert Gates’s first memoir was titled “

Robert Gates’s first memoir was titled “ Comedy inverts norms and breaks barriers. But in order to reveal, as Northrop Frye suggested it must, “absurd or irrational [patriarchal] law,” comedy requires a fall guy. There has to be somebody on whom that law can come crashing down, in all its absurdity, all its irrationality—somebody who improbably emerges at the end, unscathed or even triumphant. Buster Keaton, that beautifully deadpan clown known as “The Great Stone Face,” had the pliability—and the subtle anarchic capacity for nonviolent resistance—to fill that role like nobody else before him. Or since.

Comedy inverts norms and breaks barriers. But in order to reveal, as Northrop Frye suggested it must, “absurd or irrational [patriarchal] law,” comedy requires a fall guy. There has to be somebody on whom that law can come crashing down, in all its absurdity, all its irrationality—somebody who improbably emerges at the end, unscathed or even triumphant. Buster Keaton, that beautifully deadpan clown known as “The Great Stone Face,” had the pliability—and the subtle anarchic capacity for nonviolent resistance—to fill that role like nobody else before him. Or since. Emotions are at the same time utterly central to who we are — where would we be without them? — and also seemingly peripheral to the “real” work our brains do, understanding the world and acting within it. Why do we have emotions, anyway? Are they hardwired into the brain? Lisa Feldman Barrett is one of the world’s leading experts in the psychology of emotions, and she emphasizes that they are more constructed and less hard-wired than you might think. How we feel and express emotions can vary from culture to culture or even person to person. It’s better to think of emotions of a link between affective response and our behaviors.

Emotions are at the same time utterly central to who we are — where would we be without them? — and also seemingly peripheral to the “real” work our brains do, understanding the world and acting within it. Why do we have emotions, anyway? Are they hardwired into the brain? Lisa Feldman Barrett is one of the world’s leading experts in the psychology of emotions, and she emphasizes that they are more constructed and less hard-wired than you might think. How we feel and express emotions can vary from culture to culture or even person to person. It’s better to think of emotions of a link between affective response and our behaviors. ERDAL ARIKAN was

ERDAL ARIKAN was If some of the many thousands of human volunteers needed to test coronavirus vaccines could have been replaced by digital replicas—one of this year’s Top 10 Emerging Technologies—COVID-19 vaccines might have been developed even faster, saving untold lives. Soon virtual clinical trials could be a reality for testing new vaccines and therapies. Other technologies on the list could reduce greenhouse gas emissions by electrifying air travel and enabling sunlight to directly power the production of industrial chemicals. With “spatial” computing, the digital and physical worlds will be integrated in ways that go beyond the feats of virtual reality. And ultrasensitive sensors that exploit quantum processes will set the stage for such applications as wearable brain scanners and vehicles that can see around corners.

If some of the many thousands of human volunteers needed to test coronavirus vaccines could have been replaced by digital replicas—one of this year’s Top 10 Emerging Technologies—COVID-19 vaccines might have been developed even faster, saving untold lives. Soon virtual clinical trials could be a reality for testing new vaccines and therapies. Other technologies on the list could reduce greenhouse gas emissions by electrifying air travel and enabling sunlight to directly power the production of industrial chemicals. With “spatial” computing, the digital and physical worlds will be integrated in ways that go beyond the feats of virtual reality. And ultrasensitive sensors that exploit quantum processes will set the stage for such applications as wearable brain scanners and vehicles that can see around corners. We remember and we forget. Lots of people know that marijuana makes us forget, and researchers in the sixties and seventies wanted to understand how. They discovered that the human brain has special receptors that perfectly fit psychoactive chemicals like THC, the active agent in cannabis. But why, they wondered, would we have neuroreceptors for a foreign substance? We don’t. Those receptors are for substances produced in our own brains. The researchers discovered that we produce cannabinoids, our own version of THC, that fit those receptors exactly. The scientists had stumbled onto the neurochemical function of forgetting, never before understood. We are designed, they realized, not only to remember but also to forget. The first of the neurotransmitters discovered was named anandamide, Sanskrit for bliss.

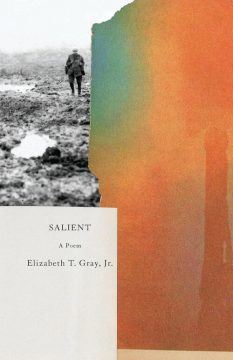

We remember and we forget. Lots of people know that marijuana makes us forget, and researchers in the sixties and seventies wanted to understand how. They discovered that the human brain has special receptors that perfectly fit psychoactive chemicals like THC, the active agent in cannabis. But why, they wondered, would we have neuroreceptors for a foreign substance? We don’t. Those receptors are for substances produced in our own brains. The researchers discovered that we produce cannabinoids, our own version of THC, that fit those receptors exactly. The scientists had stumbled onto the neurochemical function of forgetting, never before understood. We are designed, they realized, not only to remember but also to forget. The first of the neurotransmitters discovered was named anandamide, Sanskrit for bliss. Elizabeth T. Gray, Jr., would seem to write discrete lyrics but no reader gets far in her work without succumbing to an overwhelming sense that a quest is relentlessly underway. It’s a quest that can only be fathomed through a total immersion in history and landscape and immediate psychic needs of those en route: kids out for a journey to the east, soldiers heading into death, the somewhat hidden but ever present presiding consciousness of her two long poems, Series India and Salient, the poet herself as a pained and adamant devotee to some ancient faith on a pilgrimage to the edge of the abyss. The immersion is at times so deep that we might doubt the existence of the wisdom that the figures in her poems are in search of and that the poet herself feels an unassuageable need for, and yet the force of the imagination brought to bear on this imperative for transcendence, and the acute mastery of cadence, phrasing, and image, make us want it too: to see the other side of death, to feel within ourselves some ecstatic completion.

Elizabeth T. Gray, Jr., would seem to write discrete lyrics but no reader gets far in her work without succumbing to an overwhelming sense that a quest is relentlessly underway. It’s a quest that can only be fathomed through a total immersion in history and landscape and immediate psychic needs of those en route: kids out for a journey to the east, soldiers heading into death, the somewhat hidden but ever present presiding consciousness of her two long poems, Series India and Salient, the poet herself as a pained and adamant devotee to some ancient faith on a pilgrimage to the edge of the abyss. The immersion is at times so deep that we might doubt the existence of the wisdom that the figures in her poems are in search of and that the poet herself feels an unassuageable need for, and yet the force of the imagination brought to bear on this imperative for transcendence, and the acute mastery of cadence, phrasing, and image, make us want it too: to see the other side of death, to feel within ourselves some ecstatic completion.