Gopal Balachandran at the New England Review:

I recall, during the eighties, family members of mine whispering about the Indian kid in Pennsylvania convicted of murder, the Indian community being small, and the Tamil Brahmin community, to which Subu and I both belong, even smaller. Subu was the kid who’d gone down the wrong path, mixing with the wrong crowd, making for the most powerful cautionary tale of them all. Subu’s father was an academic, a physics professor and materials scientist at Penn State, who would have blended seamlessly with my parents’ friends in North Carolina, who were all vegetarian and spoke Brahminical Tamil with its idiosyncratic conjugations and vocabulary. Mrs. Vedam, as she was known in the community, always wore a sari, a thick bindi, and a thali wrapped around her neck, just like my mother. Subu, just like me, was invested with the sacred thread. Their faded color photos from the seventies and eighties could have graced any number of our peeling albums. But it was also easy to set it aside—central Pennsylvania was a world away from North Carolina. And who wanted to believe that life in middle-class suburbs, as uneven as it sometimes was for educated immigrants, could be taken away so abruptly and so easily? We all knew it could. From the hard experience of life in India, my parents knew that pure chance often led to ruin. They passed that kernel, epigenetically, to me. No wonder my nightmares of being in jail, cause unknown, started in childhood.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

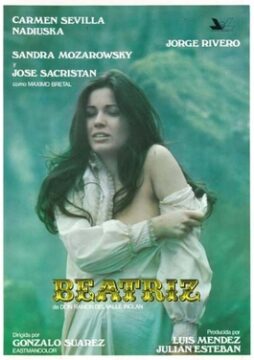

Sandra Mozarowsky was never a queen. She was never a king’s girlfriend. She was the king’s lover, though, if you believe the rumors.

Sandra Mozarowsky was never a queen. She was never a king’s girlfriend. She was the king’s lover, though, if you believe the rumors. One can reproach Viktor Orbán, a friend of US President Donald Trump and Russian President Vladimir Putin, for many things. But the Hungarian prime minister is not wrong to

One can reproach Viktor Orbán, a friend of US President Donald Trump and Russian President Vladimir Putin, for many things. But the Hungarian prime minister is not wrong to  The experiment was a striking attempt to investigate weight control. For six weeks, a group of mice gorged on lard-enriched mouse chow, then scientists infected the mice with worms. The worms wriggled beneath the animals’ skin, migrated to blood vessels that surround the intestines, and started laying eggs.

The experiment was a striking attempt to investigate weight control. For six weeks, a group of mice gorged on lard-enriched mouse chow, then scientists infected the mice with worms. The worms wriggled beneath the animals’ skin, migrated to blood vessels that surround the intestines, and started laying eggs. If any place had experience seeing civilians through war, it was the Gaza Strip. It’s much of why the place exists. That stretch of Mediterranean coast was only even named while being demarcated as a refuge for Palestinians driven off their land by Jewish forces in the 1948 war that created Israel. Gaza’s permanent status, like the fate of the Palestinians, was never decided, however. And as the decades churned on, so did the conflict.

If any place had experience seeing civilians through war, it was the Gaza Strip. It’s much of why the place exists. That stretch of Mediterranean coast was only even named while being demarcated as a refuge for Palestinians driven off their land by Jewish forces in the 1948 war that created Israel. Gaza’s permanent status, like the fate of the Palestinians, was never decided, however. And as the decades churned on, so did the conflict. W

W In 1960, the journalist and social critic Vance Packard identified a trend in American consumer culture: “planned obsolescence.” Either through superficial changes that made the older models appear outdated or through deliberately shortened product lifespans, consumers were encouraged to buy more, which also meant wasting more. It was a sales tactic, Packard found, originally popularized by a 1932 snake-oil salesman turned entrepreneur named Bernard London. London argued that manufacturers should deliberately shorten the lifespan of their products to drive continual consumer demand, boost sales, and keep the industry’s wheels turning. Just a few decades later, Packard argued that planned obsolescence was changing the very character of the American shopper: “We are being trained to live wastefully, with the idea that this is somehow patriotic,” he wrote in his book The Waste Makers.

In 1960, the journalist and social critic Vance Packard identified a trend in American consumer culture: “planned obsolescence.” Either through superficial changes that made the older models appear outdated or through deliberately shortened product lifespans, consumers were encouraged to buy more, which also meant wasting more. It was a sales tactic, Packard found, originally popularized by a 1932 snake-oil salesman turned entrepreneur named Bernard London. London argued that manufacturers should deliberately shorten the lifespan of their products to drive continual consumer demand, boost sales, and keep the industry’s wheels turning. Just a few decades later, Packard argued that planned obsolescence was changing the very character of the American shopper: “We are being trained to live wastefully, with the idea that this is somehow patriotic,” he wrote in his book The Waste Makers. By agreeing to 15% tariffs on most exports to the United States, the European Union has capitulated to Trump’s zero-sum worldview. In doing so, it has abandoned the principles of multilateralism that have long guided global trade.

By agreeing to 15% tariffs on most exports to the United States, the European Union has capitulated to Trump’s zero-sum worldview. In doing so, it has abandoned the principles of multilateralism that have long guided global trade. F

F Blood from a chicken’s crest was sprinkled over a fire, and its bleeding head was touched against hot stones and a cooking pot. The chicken was then held over the flames and its feathers burnt off before it was cooked with a set of 19 leaves and other ingredients (which must remain secret). Then, as I looked to the east, palm wine mixed with potions was poured into my eyes to ‘open’ them so I could see clearly. And, finally, a portion of the prepared meal was put to one side and later dropped into the hole of a spider (or crab) to ensure that it would continue to tell the truth. This is how, in a Cameroonian village, I was initiated as a spider diviner by the late Wajiri Bi

Blood from a chicken’s crest was sprinkled over a fire, and its bleeding head was touched against hot stones and a cooking pot. The chicken was then held over the flames and its feathers burnt off before it was cooked with a set of 19 leaves and other ingredients (which must remain secret). Then, as I looked to the east, palm wine mixed with potions was poured into my eyes to ‘open’ them so I could see clearly. And, finally, a portion of the prepared meal was put to one side and later dropped into the hole of a spider (or crab) to ensure that it would continue to tell the truth. This is how, in a Cameroonian village, I was initiated as a spider diviner by the late Wajiri Bi  S

S I, Justin Smith-Ruiu (ב), born 30071972 and uploaded 18102036, hereby submit to the Council my Petition for immediate and permanent shutdown.

I, Justin Smith-Ruiu (ב), born 30071972 and uploaded 18102036, hereby submit to the Council my Petition for immediate and permanent shutdown. This is the double-edged sword of dopamine. On one hand, this neurotransmitter might be considered the engine of human achievement. On the other hand, it’s incredibly vulnerable to manipulation by modern technology and instant gratification culture.

This is the double-edged sword of dopamine. On one hand, this neurotransmitter might be considered the engine of human achievement. On the other hand, it’s incredibly vulnerable to manipulation by modern technology and instant gratification culture.