Category: Recommended Reading

‘As If By Magic: Selected Poems’, by Paula Meehan

Eiléan Ní Chuilleanáin at Dublin Review of Books:

A poem from Paula Meehan’s second collection, Pillow Talk (1994), is called “Autobiography”. Well, in some ways a Selected Poems is like an autobiography; it expresses a sense that the life lived to date, and the work done, have some weight and perhaps some unity. Also, all autobiographies are provisional, and a Selected does not have the terminal stamp of a Collected Poems. There may yet be – one hopes there will be – many surprises in store. But there are differences: the poems included in Paula Meehan’s Selected Poems do not tell the writer’s chronological story. Rather, many of them are revisitings of phases or moments in the poet’s life, from the varying perspectives of later days. They explore those enlightening moments, when new meanings emerge from well-remembered encounters, that may only come when there is a degree of distance, for example when the adult can see what the adults in her own earlier life were about, and divine the depths of their emotions.

A poem from Paula Meehan’s second collection, Pillow Talk (1994), is called “Autobiography”. Well, in some ways a Selected Poems is like an autobiography; it expresses a sense that the life lived to date, and the work done, have some weight and perhaps some unity. Also, all autobiographies are provisional, and a Selected does not have the terminal stamp of a Collected Poems. There may yet be – one hopes there will be – many surprises in store. But there are differences: the poems included in Paula Meehan’s Selected Poems do not tell the writer’s chronological story. Rather, many of them are revisitings of phases or moments in the poet’s life, from the varying perspectives of later days. They explore those enlightening moments, when new meanings emerge from well-remembered encounters, that may only come when there is a degree of distance, for example when the adult can see what the adults in her own earlier life were about, and divine the depths of their emotions.

more here.

Recovering Old Age

Joseph E. Davis and Paul Scherz at The New Atlantis:

At other times and in other places, traditional ways of life, social classification, and metaphysical order gave shape and coherence to the course of life, providing a picture of aging well. Each period of life had its activities, duties, and forms of flourishing.

At other times and in other places, traditional ways of life, social classification, and metaphysical order gave shape and coherence to the course of life, providing a picture of aging well. Each period of life had its activities, duties, and forms of flourishing.

The periods of aging, decline, and the approach of death were especially critical. They involve some of the most complex and unsettling aspects of human experience, and so the need for a strong community to provide direction and meaning is most acute. Many social and cultural practices, such as kinship cohorts, rites of generational transition, filial duties to ancestors, hierarchies that honor wisdom, social customs that guide in grieving, and arts of suffering and dying, provided support for this time of life.

more here.

What If You Could Do It All Over? The uncanny allure of our unlived lives.

Joshua Rothman in The New Yorker:

Once, in another life, I was a tech founder. It was the late nineties, when the Web was young, and everyone was trying to cash in on the dot-com boom. In college, two of my dorm mates and I discovered that we’d each started an Internet company in high school, and we merged them to form a single, teen-age megacorp. For around six hundred dollars a month, we rented office space in the basement of a building in town. We made Web sites and software for an early dating service, an insurance-claims-processing firm, and an online store where customers could “bargain” with a cartoon avatar for overstock goods. I lived large, spending the money I made on tuition, food, and a stereo.

Once, in another life, I was a tech founder. It was the late nineties, when the Web was young, and everyone was trying to cash in on the dot-com boom. In college, two of my dorm mates and I discovered that we’d each started an Internet company in high school, and we merged them to form a single, teen-age megacorp. For around six hundred dollars a month, we rented office space in the basement of a building in town. We made Web sites and software for an early dating service, an insurance-claims-processing firm, and an online store where customers could “bargain” with a cartoon avatar for overstock goods. I lived large, spending the money I made on tuition, food, and a stereo.

In 1999—our sophomore year—we hit it big. A company that wired mid-tier office buildings with high-speed Internet hired us to build a collaborative work environment for its customers: Slack, avant la lettre. It was a huge project, entrusted to a few college students through some combination of recklessness and charity. We were terrified that we’d taken on work we couldn’t handle but also felt that we were on track to create something innovative. We blew through deadlines and budgets until the C-suite demanded a demo, which we built. Newly confident, we hired our friends, and used our corporate AmEx to expense a “business dinner” at Nobu. Unlike other kids, who were what—socializing?—I had a business card that said “Creative Director.” After midnight, in our darkened office, I nestled my Aeron chair into my ikea desk, queued up Nine Inch Nails in Winamp, scrolled code, peeped pixels, and entered the matrix. After my client work was done, I’d write short stories for my creative-writing workshops. Often, I slept on the office futon, waking to plunder the vending machine next to the loading dock, where a homeless man lived with his cart.

I liked this entrepreneurial existence—its ambition, its scrappy, near-future velocity. I thought I might move to San Francisco and work in tech. I saw a path, an opening into life. But, as the dot-com bubble burst, our client’s business was acquired by a firm that was acquired by another firm that didn’t want what we’d made.

More here.

Friday Poem

Don Arturo Says:

When I was young

there was no difference

between the way I danced

and the way tomatoes

converted themselves

into sauce

I did the waltz or a

guaguancó

which everyone your rhythm

which every one your song

The whole town was caressed

to sleep with my two-tone

shoes

Everyone

had to leave me alone

on the dirt or on the wood

They used to come from afar

and near

just to look at Arturo

disappear.

by Victor Hernández Cruz

from After Atzlan

David R. Godine, publisher 1992

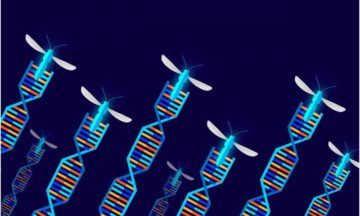

Scientists set a path for field trials of gene drive organisms

From Phys.Org:

Gene drive organisms (GDOs), developed with select traits that are genetically engineered to spread through a population, have the power to dramatically alter the way society develops solutions to a range of daunting health and environmental challenges, from controlling dengue fever and malaria to protecting crops against plant pests.

Gene drive organisms (GDOs), developed with select traits that are genetically engineered to spread through a population, have the power to dramatically alter the way society develops solutions to a range of daunting health and environmental challenges, from controlling dengue fever and malaria to protecting crops against plant pests.

But before these gene drive organisms move from the laboratory to testing in the field, scientists are proposing a course for responsible testing of this powerful technology. These issues are addressed in a new Policy Forum article on biotechnology governance, “Core commitments for field trials of gene drive organisms,” published Dec. 18, 2020 in Science by more than 40 researchers, including several University of California San Diego scientists.

“The research has progressed so rapidly with gene drive that we are now at a point when we really need to take a step back and think about the application of it and how it will impact humanity,” said Akbari, the senior author of the article and an associate professor in the UC San Diego Division of Biological Sciences. “The new commitments that address field trials are to ensure that the trials are safely implemented, transparent, publicly accountable and scientifically, politically and socially robust.”

More here.

Thursday, December 17, 2020

Beyond the Great Awokening: Reassessing the legacies of past black organizing

Adolph Reed Jr. in The New Republic:

This year marks the seventy-fifth anniversary of publication of Black Metropolis, St. Clair Drake and Horace R. Cayton’s landmark study of Chicago. Black Metropolis appeared as World War II neared its end, with U.S. political leaders fiercely debating the best ways to bring about civilian reconversion and reconstruction. Drake and Cayton recognized that the outcomes of those debates would be critical for their fellow black Americans in the postwar decades. A pair of other influential studies published around the same time, An American Dilemma: The Negro Problem and Modern Democracy by Swedish sociologist Gunnar Myrdal, and What the Negro Wants, an anthology edited by Rayford W. Logan, likewise affirmed the central challenges of racial equality in the postwar world, stressing continued expansion of New Deal social-wage policy and the steady growth of industrial unionism as keys to black advancement.

This year marks the seventy-fifth anniversary of publication of Black Metropolis, St. Clair Drake and Horace R. Cayton’s landmark study of Chicago. Black Metropolis appeared as World War II neared its end, with U.S. political leaders fiercely debating the best ways to bring about civilian reconversion and reconstruction. Drake and Cayton recognized that the outcomes of those debates would be critical for their fellow black Americans in the postwar decades. A pair of other influential studies published around the same time, An American Dilemma: The Negro Problem and Modern Democracy by Swedish sociologist Gunnar Myrdal, and What the Negro Wants, an anthology edited by Rayford W. Logan, likewise affirmed the central challenges of racial equality in the postwar world, stressing continued expansion of New Deal social-wage policy and the steady growth of industrial unionism as keys to black advancement.

Against this backdrop of social-democratic policy debate, Drake and Cayton laid out a rich account of changes in Chicago’s black population between the 1840s and the early 1940s. They focused especially on the evolving patterns of employment and housing, and the overlapping dynamics of racial discrimination, political incorporation, and structured opportunity—what they describe as the Job Ceiling—in the 1930s and 1940s.

More here.

Richard Dawkins: The insidious attacks on scientific truth

Richard Dawkins in The Spectator:

For, whether we like it or not, it is a true fact that we are cousins of kangaroos, that we share an ancestor with starfish, and that we and the starfish and kangaroo share a more remote ancestor with jellyfish. The DNA code is a digital code, differing from computer codes only in being quaternary instead of binary. We know the precise details of the intermediate stages by which the code is read in our cells, and its four-letter alphabet translated, by molecular assembly-line machines called ribosomes, into a 20-letter alphabet of amino acids, the building blocks of protein chains and so of bodies.

For, whether we like it or not, it is a true fact that we are cousins of kangaroos, that we share an ancestor with starfish, and that we and the starfish and kangaroo share a more remote ancestor with jellyfish. The DNA code is a digital code, differing from computer codes only in being quaternary instead of binary. We know the precise details of the intermediate stages by which the code is read in our cells, and its four-letter alphabet translated, by molecular assembly-line machines called ribosomes, into a 20-letter alphabet of amino acids, the building blocks of protein chains and so of bodies.

If your philosophy dismisses all that as patriarchal domination, so much the worse for your philosophy. Perhaps you should stay away from doctors with their experimentally tested medicines, and go to a shaman or witch doctor instead. If you need to travel to a conference of like-minded philosophers, you’d better not go by air. Planes fly because a lot of scientifically trained mathematicians and engineers got their sums right. They did not use ‘intuitive ways of knowing’. Whether they happened to be white and male or sky-blue-pink and hermaphrodite is supremely, triumphantly irrelevant. Logic is logic is logic, no matter if the individual who wields it also happens to wield a penis. A mathematical proof reveals a definite truth, no matter whether the mathematician ‘identifies as’ female, male or hippopotamus. If you decide to fly to that conference, Newton’s laws and Bernoulli’s principle will see you safe. And no, Newton’s Principia is not a ‘rape manual’, as was ludicrously said by the noted feminist philosopher Sandra Harding. It is a supreme work of genius by one of Homo sapiens’s most sapient specimens — who also happened to be a not very nice man.

More here.

Covid Under Biden: What Can be Done?

Dave Lindorff in CounterPunch:

As the US confronts both a political crisis of presidential succession and a worsening pandemic, it might be instructive, though perhaps not comforting, to learn that we’ve been here before.

As the US confronts both a political crisis of presidential succession and a worsening pandemic, it might be instructive, though perhaps not comforting, to learn that we’ve been here before.

In the period between the 1773 Boston Tea Party up through the start of the American Revolution with the battles of Lexington and Concord and on into late 1775, the citizens of Boston were under the thumb of a tyrannical autocrat, Gen. Thomas Gage, a leader who not only closed off economic life by shutting down Boston harbor as punishment for the city’s acts of rebellion, but also ignored a worsening smallpox epidemic, preventing local authorities from taking action to contain it.

Recounting that historic time of political and medical crisis, Charles Vidich, author of a forthcoming book Germs at Bay: Politics, Public Health & American Quarantine (Praeger, 2021), on the history of quarantines in America dating back to the early colonial era, notes that Gage’s unwillingness to heed experienced local authorities about the dangers of not dealing with smallpox led to public anger, contributed to the support in Boston for the growing insurgency against British rule, and ultimately undermined his ability to resist the uprising. Indeed the widespread smallpox epidemic in Boston quickly infected to his own Redcoat garrison in their cramped barracks in the city because of his mismanagement, diminishing the forces he had available.

More here.

John Horgan & Michael Brooks speak about the Quantum Astrologer’s Handbook

Our Stuff Weighs More Than All Living Things on the Planet

Bill McKibben in The New Yorker:

We are necessarily occupied here each week with strategies for getting ourselves out of the climate crisis—it is the world’s true Klaxon-sounding emergency. But it is worth occasionally remembering that global warming is just one measure of the human domination of our planet. We got another reminder of that unwise hegemony this week, from a study so remarkable that we should just pause and absorb it.

We are necessarily occupied here each week with strategies for getting ourselves out of the climate crisis—it is the world’s true Klaxon-sounding emergency. But it is worth occasionally remembering that global warming is just one measure of the human domination of our planet. We got another reminder of that unwise hegemony this week, from a study so remarkable that we should just pause and absorb it.

A team led by Emily Elhacham, at the Weizmann Institute of Science, in Rehovot, Israel, performed a series of staggeringly difficult calculations and concluded that 2020 was the year in which the weight of “human-made mass”—all the stuff we’ve built and accumulated—exceeded the weight of biomass on the planet. That is to say, our built environment now weighs more than all the living things, including humans, on the globe. Buildings, roads, and other infrastructure, for instance, weigh about eleven hundred gigatons, while every tree and shrub, set on a scale, would weigh about nine hundred gigatons. We have nine gigatons of plastic on the planet, compared with four gigatons of animals—every whale and elephant and bee added together. The weight of living things remains relatively static, year to year, but the weight of man-made objects is doubling every twenty years. This means that most of us likely have in our minds a very different and very wrong picture of the relative size of nature and civilization. In 1900, the weight of human-made mass was three per cent of the weight of the natural world; we were a small part of the big picture. No longer. We live on Planet Stuff.

More here.

Thursday Poem

Letter to America

pardon

the lag

in writing you

we were left

with few

letters

in your home

we were cast

as rugs

sometimes

on walls

though we

were almost

always

on floors

we served

you as

a table

a lamp

a mirror

a toy

if anything

we made

you laugh

Didion Discusses The Linguistic Surface

Faulkner as Futurist

Carl Rollyson at The Hedgehog Review:

This idea of Faulkner as fixated on the past has a long pedigree, perhaps beginning with “On The Sound and the Fury: Time in the Work of Faulkner,” a much-read 1939 essay by Jean-Paul Sartre. “In Faulkner’s work,” Sartre contends, “there is never any progression, never anything which comes from the future.” But what he describes in his quotations from the novel are Quentin Compson’s ruminations about time, not Faulkner’s. Sartre says that “Faulkner’s vision of the world can be compared to that of a man sitting in an open car and looking backwards.” But Sartre does not consider that in order for that vision to travel backwards the car has to move forward, and in that progress is change, which Warren Beck characterized as “man in motion” in his classic 1961 study, so titled, of the Snopes trilogy. Sartre—not the first philosopher to pursue an idea that overwhelms and distorts reality—argues that the past “takes on a sort of super-reality, its contours are hard and clear, unchangeable.” Tell that to any close reader of the 1936 novel Absalom, Absalom!, in which the past changes virtually moment by moment depending on who is talking.

This idea of Faulkner as fixated on the past has a long pedigree, perhaps beginning with “On The Sound and the Fury: Time in the Work of Faulkner,” a much-read 1939 essay by Jean-Paul Sartre. “In Faulkner’s work,” Sartre contends, “there is never any progression, never anything which comes from the future.” But what he describes in his quotations from the novel are Quentin Compson’s ruminations about time, not Faulkner’s. Sartre says that “Faulkner’s vision of the world can be compared to that of a man sitting in an open car and looking backwards.” But Sartre does not consider that in order for that vision to travel backwards the car has to move forward, and in that progress is change, which Warren Beck characterized as “man in motion” in his classic 1961 study, so titled, of the Snopes trilogy. Sartre—not the first philosopher to pursue an idea that overwhelms and distorts reality—argues that the past “takes on a sort of super-reality, its contours are hard and clear, unchangeable.” Tell that to any close reader of the 1936 novel Absalom, Absalom!, in which the past changes virtually moment by moment depending on who is talking.

more here.

Playing Go with Darwin

David Kakauer in Nautilus:

In 1938, Yasunari Kawabata, a young journalist in Tokyo, covered the battle between master Honinbo Shusai and apprentice Minoru Kitani for ultimate authority in the board game Go. It was one of the lengthiest matches in the history of competitive gaming—six months. In his 1968 Nobel Prize-winning novel inspired by these events, The Master of Go, Kawabata wrote of the decisive moment when, “Black has greater thickness and Black territory was secure, and the time was at hand for Otake’s [Kitani’s pseudonym in the book] own characteristic turn to offensive, for gnawing into enemy formations at which he was so adept.” A strategy that led Otake to victory.

In 1938, Yasunari Kawabata, a young journalist in Tokyo, covered the battle between master Honinbo Shusai and apprentice Minoru Kitani for ultimate authority in the board game Go. It was one of the lengthiest matches in the history of competitive gaming—six months. In his 1968 Nobel Prize-winning novel inspired by these events, The Master of Go, Kawabata wrote of the decisive moment when, “Black has greater thickness and Black territory was secure, and the time was at hand for Otake’s [Kitani’s pseudonym in the book] own characteristic turn to offensive, for gnawing into enemy formations at which he was so adept.” A strategy that led Otake to victory.

An extraordinarily complex game, Go today has become an epitaph on the tombstone in the cemetery of human defeat at the hands of algorithmic progress. (After the program AlphaGo annihilated Lee Sedol, one of Go’s best players, Sedol retired, saying his opponent was “an entity that cannot be defeated.”)

Charles Darwin was very likely the first person to have understood nature in terms of a game played across deep time. I have wondered how much further the Chess-playing naturalist might have taken this metaphor if, like Kawabata, he had studied Go. Unlike Chess, where the objective is to expose and capture the King by eliminating pieces, in Go the objective is to capture territory by surrounding enemy pieces, called stones, and by protecting unclaimed area.

More here.

What Is Soft Matter?

Philip Ball at Marginalia Review:

The term “soft matter” was coined in 1970, and has become common currency in science only in the past two or three decades. Yet the substances to which it refers – such as honey, glue, flesh, soap, leather, starch, bitumen, milk, pastes and gels – have been familiar components of our material world since antiquity. The phrase, incidentally, was coined by French scientist Madeleine Veyssié, a collaborator of physics Nobel laureate Pierre-Gilles de Gennes, one of the foremost pioneers of the field. The French term, matière molle, is something of a double entendre, which would doubtless have appealed to the suave and charismatic de Gennes, well known for his almost stereotypically Gallic romantic liaisons.

The term “soft matter” was coined in 1970, and has become common currency in science only in the past two or three decades. Yet the substances to which it refers – such as honey, glue, flesh, soap, leather, starch, bitumen, milk, pastes and gels – have been familiar components of our material world since antiquity. The phrase, incidentally, was coined by French scientist Madeleine Veyssié, a collaborator of physics Nobel laureate Pierre-Gilles de Gennes, one of the foremost pioneers of the field. The French term, matière molle, is something of a double entendre, which would doubtless have appealed to the suave and charismatic de Gennes, well known for his almost stereotypically Gallic romantic liaisons.

Modern theories that describe the molecular-scale nature of gases, simple liquids and solids were all taking shape by the end of the nineteenth century. But the sticky, viscous, rubbery or bendy fabrics of soft matter were not properly tackled until researchers such as de Gennes and Cambridge physicist Sam Edwards gave them serious attention in the 1970s and 80s; for many centuries they had been all but excluded from the conventional trio of the states of matter.

more here.

Wednesday, December 16, 2020

Respect and tolerance, people and ideas

Kenan Malik in Pandaemonium:

Should Cambridge University academics and students “tolerate” or “respect” the views of others with which they might disagree? Should we tolerate Millwall fans booing players taking the knee? Should gender-critical feminists who argue for the importance of female biology and reproduction in defining a “woman” be tolerated, or are such views themselves intolerant of trans women?

Should Cambridge University academics and students “tolerate” or “respect” the views of others with which they might disagree? Should we tolerate Millwall fans booing players taking the knee? Should gender-critical feminists who argue for the importance of female biology and reproduction in defining a “woman” be tolerated, or are such views themselves intolerant of trans women?

These are all very different discussions and debates. Underlying all of them, however, is the question of how we should understand “tolerance” and “respect”, issues that run through virtually all “free speech” and “culture wars” discussions. Too often, though, we fail to recognise how far their meanings have changed in recent years.

Tolerance as a concept has a long history and many slippery meanings. But, from 17th-century debates about religious freedom to recent discussions about mass immigration, a key understanding of tolerance is the willingness to accept ideas or practices that we might despise or disagree with but recognise are important to others. These might include the right to practise a minority faith or to possess beliefs contrary to the social consensus.

Today, however, many regard tolerance not as the willingness to allow views that some may find offensive but the restraining of unacceptable views so as to protect people from being outraged.

More here.

In seeking a means to heal our wounded planet, we should look to the painstaking, cautious craft of art conservation

Liam Heneghan in Aeon:

It is our sad lot that we love perishable things: our friends, our parents, our mentors, our partners, our pets. Those of us who incline to nature draw this consolation: most lovely natural things – the forests, the lakes, the oceans, the reefs – endure at scales remote from individual human ones. One meaning of the Anthropocene is that we must witness the unravelling of these things too. A tree we loved in childhood is gone; a favourite woodlot is felled; a local nature preserve invaded, eroded and its diversity diminished; this planet is haemorrhaging species.

It is our sad lot that we love perishable things: our friends, our parents, our mentors, our partners, our pets. Those of us who incline to nature draw this consolation: most lovely natural things – the forests, the lakes, the oceans, the reefs – endure at scales remote from individual human ones. One meaning of the Anthropocene is that we must witness the unravelling of these things too. A tree we loved in childhood is gone; a favourite woodlot is felled; a local nature preserve invaded, eroded and its diversity diminished; this planet is haemorrhaging species.

When a rare Panamanian frog was named in 2005 for George Rabb, an eminent herpetologist and friend to many in the Chicago conservation community, we celebrated this newly named animal. By the time he died in 2017, Rabb’s fringe-limbed frog (Ecnomiohyla rabborum) was assumed extinct in the wild.

There are two types of charisma: the charisma of the lit stage and that of the lambent sanctuary. Rabb’s charisma was the latter, softer, form. One of the most influential conservation biologists of his generation, he directed the Brookfield Zoo in Chicago from 1976 until 2003. He was involved in the protection of species and habitats around the globe. I first met him in the late-1990s at a meeting of the Midwestern regional conservation alliance, Chicago Wilderness. What I learned from George – who knew keenly what it is to endure loss – is that repair is possible.

More here.

David Byrne Turns His Acclaimed Musical “American Utopia” into a Picture-Book for Grown-Ups, with Vivid Illustrations by Maira Kalman

More here.

Noam Chomsky and the Left: Allies or Strange Bedfellows?

Anjan Basu in The Wire:

A couple of days before he was scheduled to discuss, on the platform of the Tata Literary Festival 2020, his recent book Internationalism or Extinction, a group of India’s social and political activists wrote an open letter to Noam Chomsky in which they suggested that he boycott the festival. They cited the less-than-wholesome credentials of the festival’s sponsors, the Tatas, in the matter of human rights and apropos of how they ran their businesses. The activists reminded Chomsky that the Tatas’ business empire had expanded over the years by ruthlessly displacing – with active help from the Indian state, and often with brute force – vast tribal communities from their traditional habitats in several Indian provinces. They also talked about open-cast mining and other deleterious business practices the Tatas continued to pursue in flagrant disregard of environmental concerns. By lending his formidable name and his enormous prestige to the festival, the activists believed, Chomsky would only help “erase their (the Tatas’) crimes from public consciousness”.

A couple of days before he was scheduled to discuss, on the platform of the Tata Literary Festival 2020, his recent book Internationalism or Extinction, a group of India’s social and political activists wrote an open letter to Noam Chomsky in which they suggested that he boycott the festival. They cited the less-than-wholesome credentials of the festival’s sponsors, the Tatas, in the matter of human rights and apropos of how they ran their businesses. The activists reminded Chomsky that the Tatas’ business empire had expanded over the years by ruthlessly displacing – with active help from the Indian state, and often with brute force – vast tribal communities from their traditional habitats in several Indian provinces. They also talked about open-cast mining and other deleterious business practices the Tatas continued to pursue in flagrant disregard of environmental concerns. By lending his formidable name and his enormous prestige to the festival, the activists believed, Chomsky would only help “erase their (the Tatas’) crimes from public consciousness”.

Noam Chomsky responded by telling the activists that he wanted to go ahead with the programme he had committed to, but that he and his interlocutor, Vijay Prashad, would begin the proceedings by reading out a prepared statement in which they would spell out their views on big business including the Tatas. Obviously they were not going to present a particularly edifying picture of the business conglomerate’s activities. Expectedly, therefore, when the festival organisers got wind of Chomsky’s intentions, they cancelled the programme, without, of course, telling him why.

More here.