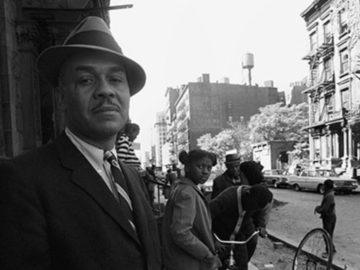

Brian Morton in Dissent:

I first heard the phrase “Stay in your lane” a few years ago, in a writing workshop I was teaching. We were talking about a story that a student in the group, an Asian-American man, had written about an African-American family.

I first heard the phrase “Stay in your lane” a few years ago, in a writing workshop I was teaching. We were talking about a story that a student in the group, an Asian-American man, had written about an African-American family.

There was a lot to criticize about the story, including an abundance of clichés about the lives of Black Americans. I had expected the class to offer suggestions for improvement. What I hadn’t expected was that some students would tell the writer that he shouldn’t have written the story at all. As one of them put it, if a member of a relatively privileged group writes a story about a member of a marginalized group, this is an act of cultural appropriation and therefore does harm.

Arguments about cultural appropriation make the news every month or two. Two women from Portland, after enjoying the food during a trip to Mexico, open a burrito cart when they return home but, assailed by online activists, close their business within months. A yoga class at a university in Canada is shut down by student protests. The author of a young-adult novel, criticized for writing about characters from backgrounds different from his own, apologizes and withdraws his book from circulation. Such a wide variety of acts and practices is condemned as cultural appropriation that it can be hard to tell what cultural appropriation is.

More here.

Unlike the September 11 attacks and the 2008 financial crisis – the first two supposedly global events of the 21st century – this pandemic has not spared anyone anywhere, and its consequences will continue to be felt for decades in every corner of the world.

Unlike the September 11 attacks and the 2008 financial crisis – the first two supposedly global events of the 21st century – this pandemic has not spared anyone anywhere, and its consequences will continue to be felt for decades in every corner of the world. Hindi—the original name of the language now known as Urdu—and modern Hindi are two distinct languages. Despite being a fairly new language, notions regarding Urdu’s origins and history are as hotly debated amongst the public at large as among scholars and linguists. Interestingly, the name Urdu gained currency circa 1857, with the formal cessation of Mughal rule. Hindi was the name commonly used until the second decade of the 20th century by none other than Iqbal, a poet whose poetry is overtly Islamic. His use of ‘Hindi’, instead of ‘Urdu’, gives lie to determined efforts, after the establishment of the Muslim League in 1903, to paint Urdu as the language of Muslims, as opposed to modern Hindi as the language of Hindus. Urdu would then be utilised to mobilise Muslim support for a new country. The publication of Shamsur Rahman Faruqi’s seminal work, Urdu ka Ibtedaee Zamana: Adabi Tarikh o Tahzib ke Pahlu (1999), followed by its original English version (Early Urdu Literary Culture and History [2001]), compelled the revision of many current and honoured notions about early Urdu and its literary culture. In many ways, it was a pioneering work which needs to be revisited. The book demolished myths and assumptions about the early history of the language as it developed in and around Delhi from the late 17th century onwards. It provided new information—not yet challenged—about the origin of the language name ‘Urdu’, and many other aspects of Urdu’s literary history.

Hindi—the original name of the language now known as Urdu—and modern Hindi are two distinct languages. Despite being a fairly new language, notions regarding Urdu’s origins and history are as hotly debated amongst the public at large as among scholars and linguists. Interestingly, the name Urdu gained currency circa 1857, with the formal cessation of Mughal rule. Hindi was the name commonly used until the second decade of the 20th century by none other than Iqbal, a poet whose poetry is overtly Islamic. His use of ‘Hindi’, instead of ‘Urdu’, gives lie to determined efforts, after the establishment of the Muslim League in 1903, to paint Urdu as the language of Muslims, as opposed to modern Hindi as the language of Hindus. Urdu would then be utilised to mobilise Muslim support for a new country. The publication of Shamsur Rahman Faruqi’s seminal work, Urdu ka Ibtedaee Zamana: Adabi Tarikh o Tahzib ke Pahlu (1999), followed by its original English version (Early Urdu Literary Culture and History [2001]), compelled the revision of many current and honoured notions about early Urdu and its literary culture. In many ways, it was a pioneering work which needs to be revisited. The book demolished myths and assumptions about the early history of the language as it developed in and around Delhi from the late 17th century onwards. It provided new information—not yet challenged—about the origin of the language name ‘Urdu’, and many other aspects of Urdu’s literary history. Uncle Vernon was cool, tall, hazel-eyed, and brown-skinned. He dressed in the latest fashions and wore leather long after the sixties. Of all of my father’s three brothers, Vernon was the artist—a painter and photographer in a decidedly nonartistic family. To demonstrate his flair for the dramatic and avant-garde, his apartment was stylishly decorated. It showcased a faux brown suede, crushed velvet couch with square rectangular pieces that sectioned off like geography, accentuated by a round glass coffee table with decorative steel legs. It was pulled together by a large seventies organizer and stereo that nearly covered the length of an entire wall. As a final touch, dangling from the shelves was a small collection of antique long-legged dolls. This was my uncle and memories of his apartment were never so clear as the day I headed there with my first boyfriend, Shaun Lyle.

Uncle Vernon was cool, tall, hazel-eyed, and brown-skinned. He dressed in the latest fashions and wore leather long after the sixties. Of all of my father’s three brothers, Vernon was the artist—a painter and photographer in a decidedly nonartistic family. To demonstrate his flair for the dramatic and avant-garde, his apartment was stylishly decorated. It showcased a faux brown suede, crushed velvet couch with square rectangular pieces that sectioned off like geography, accentuated by a round glass coffee table with decorative steel legs. It was pulled together by a large seventies organizer and stereo that nearly covered the length of an entire wall. As a final touch, dangling from the shelves was a small collection of antique long-legged dolls. This was my uncle and memories of his apartment were never so clear as the day I headed there with my first boyfriend, Shaun Lyle. Perry Anderson in the LRB:

Perry Anderson in the LRB: Thomas Geoghegan in The New Republic:

Thomas Geoghegan in The New Republic: Malcolm Keating in Psyche:

Malcolm Keating in Psyche: In the summer of 1944, a camera was smuggled out of Auschwitz. Inside it was a roll of film with four images from the gas chambers at Birkenau, taken by members of the Jewish Sonderkommando. These photos were distributed worldwide by the Polish resistance. Two of them appear to have been taken in quick succession, discreetly, from within a shadowed doorframe. The other pair, one of which is blurred, appear to have been shot at the hip from a distance. The photos show Jewish women stripping before the gas chamber, and dead bodies waiting to be incinerated. White smoke billows as other bodies burn.

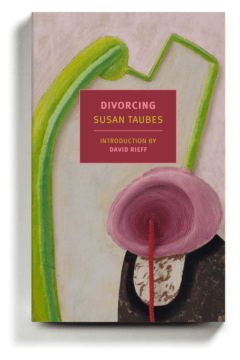

In the summer of 1944, a camera was smuggled out of Auschwitz. Inside it was a roll of film with four images from the gas chambers at Birkenau, taken by members of the Jewish Sonderkommando. These photos were distributed worldwide by the Polish resistance. Two of them appear to have been taken in quick succession, discreetly, from within a shadowed doorframe. The other pair, one of which is blurred, appear to have been shot at the hip from a distance. The photos show Jewish women stripping before the gas chamber, and dead bodies waiting to be incinerated. White smoke billows as other bodies burn. Because there are many things to say about Susan Taubes’s remarkable 1969 novel “Divorcing,” and many of those things concern the grim side of both real life and life in the book, I’d like to start by saying that it’s funny. It’s not a comic novel, by any stretch, but neglecting to mention its humor would shortchange it and deform one’s initial idea of it.

Because there are many things to say about Susan Taubes’s remarkable 1969 novel “Divorcing,” and many of those things concern the grim side of both real life and life in the book, I’d like to start by saying that it’s funny. It’s not a comic novel, by any stretch, but neglecting to mention its humor would shortchange it and deform one’s initial idea of it. T

T

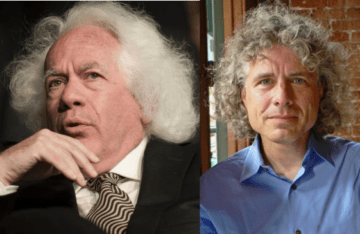

Back in 2013, another in a long line of tussles over scientism broke out. Leon Wieseltier, literary editor of The New Republic,

Back in 2013, another in a long line of tussles over scientism broke out. Leon Wieseltier, literary editor of The New Republic,