Laura Marris at The Point:

It’s a little-known fact that Camus worked briefly as a meteorologist. For almost a year, from 1937-38, he wore a lab coat at the Algiers Geophysics Institute and catalogued measurements of atmospheric pressure from hundreds of weather stations across North Africa. The data had been piling up, and despite the arrogance of their imperial ambitions, the men who ran the Institute couldn’t attract enough funding. They didn’t have the money to hire a scientist trained for this “exacting and, in effect, stupefying task.”3 Nonetheless, Camus’s supervisor, Lucien Petitjean, was pleased with his work. By the end of his time at the Institute, Camus had plotted curves for 27 years of barometric pressures from 121 weather stations. He also made calculations, averaging monthly meteorological data. This work must have given him a granular picture of the weather, one that was so dry and clinical it was at odds with his experience of the natural world. “Like in all sciences of description (statistics—which collects facts—) the biggest problem in meteorology is a practical problem: that of replacing missing observations,” he wrote in his notebook. “Temperature varies from one minute to the next,” he clarified. “This experiment shifts too much to be stabilized into mathematical concepts. Observation here represents an arbitrary slice of reality.”

It’s a little-known fact that Camus worked briefly as a meteorologist. For almost a year, from 1937-38, he wore a lab coat at the Algiers Geophysics Institute and catalogued measurements of atmospheric pressure from hundreds of weather stations across North Africa. The data had been piling up, and despite the arrogance of their imperial ambitions, the men who ran the Institute couldn’t attract enough funding. They didn’t have the money to hire a scientist trained for this “exacting and, in effect, stupefying task.”3 Nonetheless, Camus’s supervisor, Lucien Petitjean, was pleased with his work. By the end of his time at the Institute, Camus had plotted curves for 27 years of barometric pressures from 121 weather stations. He also made calculations, averaging monthly meteorological data. This work must have given him a granular picture of the weather, one that was so dry and clinical it was at odds with his experience of the natural world. “Like in all sciences of description (statistics—which collects facts—) the biggest problem in meteorology is a practical problem: that of replacing missing observations,” he wrote in his notebook. “Temperature varies from one minute to the next,” he clarified. “This experiment shifts too much to be stabilized into mathematical concepts. Observation here represents an arbitrary slice of reality.”

more here.

It’s early, but Republicans have already seized on their strategy for winning the 2022 and 2024 elections. Of course, it does not depend on mundane tactics like “running on their record” or “making robust arguments about how their policies are better than their opponents.” The GOP is instead returning to the well that has, time and again, paid off handsomely: feigning umbrage over culture war flashpoints, usually ones wholly invented by the right or propped up with lies, to distract from substantive policy debates that actually impact American lives.

It’s early, but Republicans have already seized on their strategy for winning the 2022 and 2024 elections. Of course, it does not depend on mundane tactics like “running on their record” or “making robust arguments about how their policies are better than their opponents.” The GOP is instead returning to the well that has, time and again, paid off handsomely: feigning umbrage over culture war flashpoints, usually ones wholly invented by the right or propped up with lies, to distract from substantive policy debates that actually impact American lives. A new study asks the question: Do conversations end when people want them to? The short answer, it turns out, is no. The study, published this week in the journal the

A new study asks the question: Do conversations end when people want them to? The short answer, it turns out, is no. The study, published this week in the journal the  How can we summarise the Covid year from a broad historical perspective? Many people believe that the terrible toll coronavirus has taken demonstrates humanity’s helplessness in the face of nature’s might. In fact, 2020 has shown that humanity is far from helpless. Epidemics are no longer uncontrollable forces of nature. Science has turned them into a manageable challenge.

How can we summarise the Covid year from a broad historical perspective? Many people believe that the terrible toll coronavirus has taken demonstrates humanity’s helplessness in the face of nature’s might. In fact, 2020 has shown that humanity is far from helpless. Epidemics are no longer uncontrollable forces of nature. Science has turned them into a manageable challenge. The search for AI has always been about trying to build

The search for AI has always been about trying to build  No problem concerns journalists and press-watchers so much these days as the proliferation of conspiracy theories and misinformation on the internet. “We never confronted this level of conspiracy thinking in the U.S. previously,” Marty Baron, the former executive editor of The Washington Post, told Der Spiegel in a

No problem concerns journalists and press-watchers so much these days as the proliferation of conspiracy theories and misinformation on the internet. “We never confronted this level of conspiracy thinking in the U.S. previously,” Marty Baron, the former executive editor of The Washington Post, told Der Spiegel in a  Higgie’s book is a riposte to Renoir and centuries of unknowing and misjudging. Reading it is like travelling with an ever-excited companion who has lots to say, not all of it profound as it tumbles out in profusion and partisanship, and not always quite trustworthy, but always compelling. She is rightly enraged at the historical neglect of women artists. The marvellous illustrations here confirm her assessment of the quality of their work. Few nowadays would argue with her proposition that the history of art is ‘the history of many women not receiving their dues’. Beginning research for this book, she was ‘staggered’ by the depth and variety of paintings made by women, despite the formidable restrictions placed in their way, and despite believing herself already well informed on the subject. Ending her book, I felt much the same way, and excited at the prospect of finding out more.

Higgie’s book is a riposte to Renoir and centuries of unknowing and misjudging. Reading it is like travelling with an ever-excited companion who has lots to say, not all of it profound as it tumbles out in profusion and partisanship, and not always quite trustworthy, but always compelling. She is rightly enraged at the historical neglect of women artists. The marvellous illustrations here confirm her assessment of the quality of their work. Few nowadays would argue with her proposition that the history of art is ‘the history of many women not receiving their dues’. Beginning research for this book, she was ‘staggered’ by the depth and variety of paintings made by women, despite the formidable restrictions placed in their way, and despite believing herself already well informed on the subject. Ending her book, I felt much the same way, and excited at the prospect of finding out more. On a road into New Delhi, countless cars a day speed over tonnes of plastic bags, bottle tops and discarded polystyrene cups. In a single kilometre, a driver covers one tonne of plastic waste. But far from being an unpleasant journey through a sea of litter, this road is smooth and well-maintained – in fact the plastic that each driver passes over isn’t visible to the naked eye. It is simply a part of the road. This road, stretching from New Delhi to nearby Meerut, was laid using a system developed by Rajagopalan Vasudevan, a professor of chemistry at the Thiagarajar College of Engineering in India, which replaces 10% of a road’s bitumen with repurposed plastic waste.

On a road into New Delhi, countless cars a day speed over tonnes of plastic bags, bottle tops and discarded polystyrene cups. In a single kilometre, a driver covers one tonne of plastic waste. But far from being an unpleasant journey through a sea of litter, this road is smooth and well-maintained – in fact the plastic that each driver passes over isn’t visible to the naked eye. It is simply a part of the road. This road, stretching from New Delhi to nearby Meerut, was laid using a system developed by Rajagopalan Vasudevan, a professor of chemistry at the Thiagarajar College of Engineering in India, which replaces 10% of a road’s bitumen with repurposed plastic waste. When Eugen Sandow (pictured) opened his first School of Physical Culture in London in the summer of 1897, he ensured that its decor matched his personal brand. On arrival at 32A St James’s Street, visitors found themselves facing a life-sized statue of the founder himself. A nearby oil painting depicted Sandow as an ancient gladiator. In both cases his sculpted physique evoked the spirit of Greek classicism that Sandow, regarded in his heyday as the “perfect man”, strove to embody.

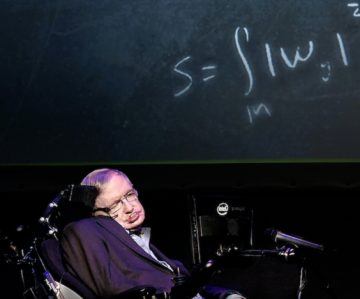

When Eugen Sandow (pictured) opened his first School of Physical Culture in London in the summer of 1897, he ensured that its decor matched his personal brand. On arrival at 32A St James’s Street, visitors found themselves facing a life-sized statue of the founder himself. A nearby oil painting depicted Sandow as an ancient gladiator. In both cases his sculpted physique evoked the spirit of Greek classicism that Sandow, regarded in his heyday as the “perfect man”, strove to embody. In one of his 2016 Reith Lectures, Stephen Hawking said an odd thing. “People have searched for mini black holes… but have so far not found any,” he intoned with his trademark voice synthesiser. “This is a pity, because if they had I would have got a Nobel Prize.” The audience at the Royal Institution in London (which included me) laughed. But I was struck by how unusual it was for a scientist to state publicly that their work warranted a Nobel. It was no passing comment. A few minutes later, Hawking described how mini black holes—which he predicted in the early 1970s—might yet be seen in the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) at CERN in Geneva. “So I might get a Nobel Prize after all,” he added, to more laughter.

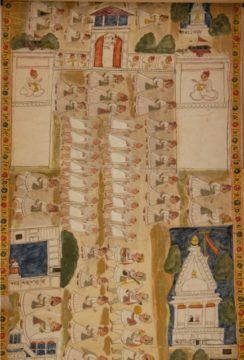

In one of his 2016 Reith Lectures, Stephen Hawking said an odd thing. “People have searched for mini black holes… but have so far not found any,” he intoned with his trademark voice synthesiser. “This is a pity, because if they had I would have got a Nobel Prize.” The audience at the Royal Institution in London (which included me) laughed. But I was struck by how unusual it was for a scientist to state publicly that their work warranted a Nobel. It was no passing comment. A few minutes later, Hawking described how mini black holes—which he predicted in the early 1970s—might yet be seen in the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) at CERN in Geneva. “So I might get a Nobel Prize after all,” he added, to more laughter. I first encountered a snippet of the seventy-two-foot-long painted invitation letter as a four by six-inch reproduction in Susan Gole’s pioneering Indian Maps and Plans (New Delhi: Manohar, 54). No measurements were noted. Yet, I imagined the scroll’s spread—it motivated me to abandon archival research in the British Library and travel to Bikaner at short notice in April 2009. Housed in the Abhay Jain Granthalaya, maintained as the personal library of the renowned scholar of Jain religion and culture, Dr. Abhaychand Nahata, I never anticipated the extent to which this artifact would impact my research. As the librarian, Mr. Chopra, helped me carefully unfurl the scroll, held together by a spindle on either end in an openable glass box, Udaipur’s painted streets, shops, and sights were revealed. At any given instance, I could examine only a two-foot section of the scroll. I attempted to retain the painted vignette past my line of vision just as we stack storefronts in our memory while walking through a busy bazaar. Similarly, the composite image, presented within the rectangular window of the

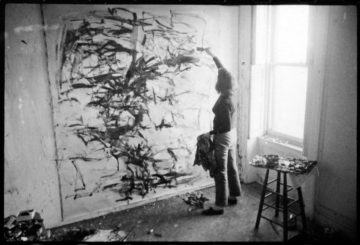

I first encountered a snippet of the seventy-two-foot-long painted invitation letter as a four by six-inch reproduction in Susan Gole’s pioneering Indian Maps and Plans (New Delhi: Manohar, 54). No measurements were noted. Yet, I imagined the scroll’s spread—it motivated me to abandon archival research in the British Library and travel to Bikaner at short notice in April 2009. Housed in the Abhay Jain Granthalaya, maintained as the personal library of the renowned scholar of Jain religion and culture, Dr. Abhaychand Nahata, I never anticipated the extent to which this artifact would impact my research. As the librarian, Mr. Chopra, helped me carefully unfurl the scroll, held together by a spindle on either end in an openable glass box, Udaipur’s painted streets, shops, and sights were revealed. At any given instance, I could examine only a two-foot section of the scroll. I attempted to retain the painted vignette past my line of vision just as we stack storefronts in our memory while walking through a busy bazaar. Similarly, the composite image, presented within the rectangular window of the  THE CANVAS IS LARGE, standing more than seven feet tall and six feet wide. Painted on a white ground, the composition reveals numerous areas in which white paint has been energetically brushed over marks in other colors, progressively editing a roiling chaos of gestures down to a sparer, more defined structure with several especially prominent elements. In the upper register, just left of center, overlapping brushstrokes in shades of red, black, blue-green, and yellow combine to form a thick vertical line, as if marking out the operative axis. Just below this upright element, there appears a dense flurry of multicolored gestures. Clustered in a roughly horizontal zone, this array tapers to either side but is both extended and visually weighted toward the right. Also on the right, a bit farther down, dozens of brushstrokes have again been layered one atop the other, creating a diagonal band. At the very bottom of the picture, yet another cluster of predominantly oblique gestures form a rough wedge, drawing the eye to the lower right. The artist has signed her first initial and last name: J. MITCHELL.

THE CANVAS IS LARGE, standing more than seven feet tall and six feet wide. Painted on a white ground, the composition reveals numerous areas in which white paint has been energetically brushed over marks in other colors, progressively editing a roiling chaos of gestures down to a sparer, more defined structure with several especially prominent elements. In the upper register, just left of center, overlapping brushstrokes in shades of red, black, blue-green, and yellow combine to form a thick vertical line, as if marking out the operative axis. Just below this upright element, there appears a dense flurry of multicolored gestures. Clustered in a roughly horizontal zone, this array tapers to either side but is both extended and visually weighted toward the right. Also on the right, a bit farther down, dozens of brushstrokes have again been layered one atop the other, creating a diagonal band. At the very bottom of the picture, yet another cluster of predominantly oblique gestures form a rough wedge, drawing the eye to the lower right. The artist has signed her first initial and last name: J. MITCHELL. IT’S ONE OF THE MIGHTIEST RIVERS you will never see, carrying some 30 times more water than all the world’s freshwater rivers combined. In the North Atlantic, one arm of the Gulf Stream breaks toward Iceland, transporting vast amounts of warmth far northward, by one estimate supplying Scandinavia with heat equivalent to 78,000 times its current energy use. Without this current — a heat pump on a planetary scale — scientists believe that great swathes of the world might look quite different.

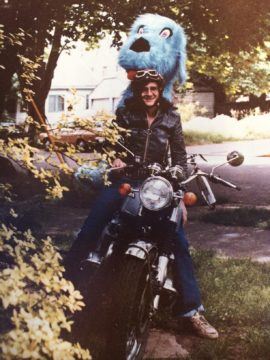

IT’S ONE OF THE MIGHTIEST RIVERS you will never see, carrying some 30 times more water than all the world’s freshwater rivers combined. In the North Atlantic, one arm of the Gulf Stream breaks toward Iceland, transporting vast amounts of warmth far northward, by one estimate supplying Scandinavia with heat equivalent to 78,000 times its current energy use. Without this current — a heat pump on a planetary scale — scientists believe that great swathes of the world might look quite different. It sounds like the plot of some cop-buddy movie: an anarchic hippie social worker (Snoop Dogg or Owen Wilson) is forced to team up with a straight-laced conservative cop (Clint Eastwood, the Rock). Chaos and hilarity ensue. Life lessons are learned. In this case, it actually happened.

It sounds like the plot of some cop-buddy movie: an anarchic hippie social worker (Snoop Dogg or Owen Wilson) is forced to team up with a straight-laced conservative cop (Clint Eastwood, the Rock). Chaos and hilarity ensue. Life lessons are learned. In this case, it actually happened.