Jackie Leach Scully in Nature:

What we used to call genetic engineering has been subject to decades of bioethical scrutiny. Then, the arrival of CRISPR — which allows researchers to cut and paste gene sequences with vastly improved accuracy and efficiency — catapulted reassuringly distant science fiction into a pressing reality, and helped to concentrate minds. There’s now enough technical and popular writing on the technology and its ethics to fill many bookshelves. Given that not even ten years have passed since the first papers showing a practical use for CRISPR in human genome editing, these accounts inevitably go over much of the same territory. The differences are in the authors’ perspectives — broadly enthusiastic about the possibilities of genome editing, or not — and whether the focus is on the discoveries, the ramifications, the personalities involved or some combination. Two new books on the topic differ markedly in reach, style and emphasis. Reading them together gives insight into what the CRISPR story means — for knowledge, for society and for research as an endeavour.

What we used to call genetic engineering has been subject to decades of bioethical scrutiny. Then, the arrival of CRISPR — which allows researchers to cut and paste gene sequences with vastly improved accuracy and efficiency — catapulted reassuringly distant science fiction into a pressing reality, and helped to concentrate minds. There’s now enough technical and popular writing on the technology and its ethics to fill many bookshelves. Given that not even ten years have passed since the first papers showing a practical use for CRISPR in human genome editing, these accounts inevitably go over much of the same territory. The differences are in the authors’ perspectives — broadly enthusiastic about the possibilities of genome editing, or not — and whether the focus is on the discoveries, the ramifications, the personalities involved or some combination. Two new books on the topic differ markedly in reach, style and emphasis. Reading them together gives insight into what the CRISPR story means — for knowledge, for society and for research as an endeavour.

Henry Greely, author of CRISPR People, is a bioethicist with a legal background. His focus is the now-familiar tale of biophysicist He Jiankui’s attempt to change the DNA of human embryos, with the aim of producing the first genetically edited human babies. Greely describes the science, ethics and legal framework of genome editing before CRISPR; how that technology changed the game; what He Jiankui actually did in the laboratory, as far as we know; and how the world responded to the news of the births of genome-edited twins in 2018.

More here.

I’ve never really understood why Georg Trakl talks about foreheads so much. I mean, you can imagine the word coming up once in a poem for some reason or other. I can even see that there is something fascinating about foreheads in that they are both of and not of the face. That’s to say, you don’t generally get a face without a forehead. The forehead sets up the face. And yet, it’s not really part of the face per se. The forehead is claimed to some degree by the rest of the head. It is a glimpse of the skull. It is a stoic and mostly featureless reminder that behind the bones of the head are the squishy parts of the brain. So, yes, I acknowledge that foreheads are, perhaps, more intriguing than at first they may seem.

I’ve never really understood why Georg Trakl talks about foreheads so much. I mean, you can imagine the word coming up once in a poem for some reason or other. I can even see that there is something fascinating about foreheads in that they are both of and not of the face. That’s to say, you don’t generally get a face without a forehead. The forehead sets up the face. And yet, it’s not really part of the face per se. The forehead is claimed to some degree by the rest of the head. It is a glimpse of the skull. It is a stoic and mostly featureless reminder that behind the bones of the head are the squishy parts of the brain. So, yes, I acknowledge that foreheads are, perhaps, more intriguing than at first they may seem. On a spectrum of philosophical topics, one might be tempted to put mathematics and morality on opposite ends. Math is one of the most pristine and rigorously-developed areas of human thought, while morality is notoriously contentious and resistant to consensus. But the more you dig into the depths, the more alike these two fields appear to be. Justin Clarke-Doane argues that they are very much alike indeed, especially when it comes to questions of “reality” and “objectivity” — but that they aren’t quite exactly analogous. We get a little bit into the weeds, but this is a case where close attention will pay off.

On a spectrum of philosophical topics, one might be tempted to put mathematics and morality on opposite ends. Math is one of the most pristine and rigorously-developed areas of human thought, while morality is notoriously contentious and resistant to consensus. But the more you dig into the depths, the more alike these two fields appear to be. Justin Clarke-Doane argues that they are very much alike indeed, especially when it comes to questions of “reality” and “objectivity” — but that they aren’t quite exactly analogous. We get a little bit into the weeds, but this is a case where close attention will pay off. A few weeks ago I served, as I sometimes do, on a dissertation-defense committee at a certain venerable Old World university. The event took place in a building whose foundations date to the thirteenth century, in a specialized “salle de soutenance” constructed in the nineteenth. The defendant was made to sit at a small desk beneath a looming podium, where we, the honorable members of the jury, were solemnly seated. The borrowed vocabulary from the world of the criminal trial is intentional and unmistakable. As usual I tried to play my part and look as grim and serious as possible. I confess I find it fairly easy, at least for a short time, to get swept up by the spirit of such rituals.

A few weeks ago I served, as I sometimes do, on a dissertation-defense committee at a certain venerable Old World university. The event took place in a building whose foundations date to the thirteenth century, in a specialized “salle de soutenance” constructed in the nineteenth. The defendant was made to sit at a small desk beneath a looming podium, where we, the honorable members of the jury, were solemnly seated. The borrowed vocabulary from the world of the criminal trial is intentional and unmistakable. As usual I tried to play my part and look as grim and serious as possible. I confess I find it fairly easy, at least for a short time, to get swept up by the spirit of such rituals. For Shah, migration has always been the rule rather than the exception, but it will become even more common as the planet warms. The low-lying country of Bangladesh has a population of more than 150 million. If the seas rise three feet—quite likely to happen this century—a fifth of its land, on which some 30 million people live, will be submerged. Those 30 million will be forced to move, and when they do, it will matter how they’re regarded. As “Bangladeshis” perpetually out of place, they will likely struggle to find safe berth. It would be better, Shah suggests, to drop the labels, recognize human beings as a migratory species, and build institutions around that fact.

For Shah, migration has always been the rule rather than the exception, but it will become even more common as the planet warms. The low-lying country of Bangladesh has a population of more than 150 million. If the seas rise three feet—quite likely to happen this century—a fifth of its land, on which some 30 million people live, will be submerged. Those 30 million will be forced to move, and when they do, it will matter how they’re regarded. As “Bangladeshis” perpetually out of place, they will likely struggle to find safe berth. It would be better, Shah suggests, to drop the labels, recognize human beings as a migratory species, and build institutions around that fact. We don’t read diarists because we admire them, but because they were there, and they note down what they saw and heard. “Chips” Channon was wrong about almost everything. But do we read Boswell, Casanova, Pepys, Alan Clark or even Sasha Swire for their judgement? We do not. We read them to be taken aback, and to question ourselves. Exhausting, massive, genuinely shocking, and still revelatory, this new edition of the Channon diaries is a work of irrigation and genuine scholarship. Few people may read them from cover to cover, but the stories they contain will rattle noisily around our culture for decades ahead.

We don’t read diarists because we admire them, but because they were there, and they note down what they saw and heard. “Chips” Channon was wrong about almost everything. But do we read Boswell, Casanova, Pepys, Alan Clark or even Sasha Swire for their judgement? We do not. We read them to be taken aback, and to question ourselves. Exhausting, massive, genuinely shocking, and still revelatory, this new edition of the Channon diaries is a work of irrigation and genuine scholarship. Few people may read them from cover to cover, but the stories they contain will rattle noisily around our culture for decades ahead. On 7 March 1965, the nation came to grips with one of the most iconic images synonymous with the fight for voting rights and equality.

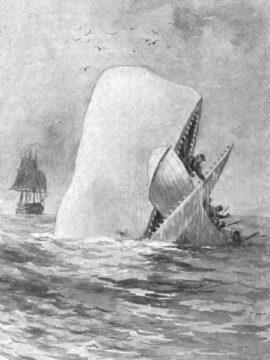

On 7 March 1965, the nation came to grips with one of the most iconic images synonymous with the fight for voting rights and equality.  For the mathematician Sarah Hart, a close reading of “Moby-Dick” reveals not merely (per D.H. Lawrence) “one of the strangest and most wonderful books in the world” and “the greatest book of the sea ever written,” but also a work awash in mathematical metaphors. “Herman Melville, he really liked mathematics — you can see it in his books,” said Dr. Hart, a professor at Birkbeck, University of London, during a February talk on “

For the mathematician Sarah Hart, a close reading of “Moby-Dick” reveals not merely (per D.H. Lawrence) “one of the strangest and most wonderful books in the world” and “the greatest book of the sea ever written,” but also a work awash in mathematical metaphors. “Herman Melville, he really liked mathematics — you can see it in his books,” said Dr. Hart, a professor at Birkbeck, University of London, during a February talk on “ A lost poem by

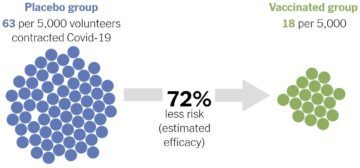

A lost poem by  Efficacy is a crucial concept in vaccine trials, but it’s also a tricky one. If a vaccine has an efficacy of, say, 95 percent, that doesn’t mean that 5 percent of people who receive that vaccine will get Covid-19. And just because one vaccine ends up with a higher efficacy estimate than another in trials doesn’t necessarily mean it’s superior. Here’s why.

Efficacy is a crucial concept in vaccine trials, but it’s also a tricky one. If a vaccine has an efficacy of, say, 95 percent, that doesn’t mean that 5 percent of people who receive that vaccine will get Covid-19. And just because one vaccine ends up with a higher efficacy estimate than another in trials doesn’t necessarily mean it’s superior. Here’s why. More than two decades after the country democratized, a sense of insecurity persists in daily life in South Africa, and access to the public good of security has remained astonishingly unequal. In lieu of equitable access to security, affluent neighborhoods are adorned with nine-foot cement walls, expandable steel security gates, and armed guards. Even the state itself employs private security officers, hiring private guards to patrol the outside of police precincts and to carry out unseemly land evictions. Private security in South Africa is like a snake eating its own tail, as the government itself invests in the firms that are undermining its own authority.

More than two decades after the country democratized, a sense of insecurity persists in daily life in South Africa, and access to the public good of security has remained astonishingly unequal. In lieu of equitable access to security, affluent neighborhoods are adorned with nine-foot cement walls, expandable steel security gates, and armed guards. Even the state itself employs private security officers, hiring private guards to patrol the outside of police precincts and to carry out unseemly land evictions. Private security in South Africa is like a snake eating its own tail, as the government itself invests in the firms that are undermining its own authority. In 1966, a young American journalist named Frances FitzGerald began publishing articles from South Vietnam in leading magazines, including this one. She was the unlikeliest of war correspondents—born into immense privilege, a daughter of the high-WASP ascendancy. Her father, Desmond FitzGerald, was a top CIA official; her mother, Marietta Tree, a socialite and liberal activist. FitzGerald was raised with servants and horses, and she had to fend off advances from the likes of Adlai Stevenson (her mother’s lover) and Henry Kissinger. Her family contacts got her through the door of feature journalism in New York, but as a woman, she was denied the chance to pursue the serious work she wanted to do. She escaped this jeweled trap by making her own way to Saigon at age 25, just as the American war was escalating.

In 1966, a young American journalist named Frances FitzGerald began publishing articles from South Vietnam in leading magazines, including this one. She was the unlikeliest of war correspondents—born into immense privilege, a daughter of the high-WASP ascendancy. Her father, Desmond FitzGerald, was a top CIA official; her mother, Marietta Tree, a socialite and liberal activist. FitzGerald was raised with servants and horses, and she had to fend off advances from the likes of Adlai Stevenson (her mother’s lover) and Henry Kissinger. Her family contacts got her through the door of feature journalism in New York, but as a woman, she was denied the chance to pursue the serious work she wanted to do. She escaped this jeweled trap by making her own way to Saigon at age 25, just as the American war was escalating. Everyone seems to be talking about the problems with physics: Peter Woit’s book Not Even Wrong, Lee Smolin’s The Trouble With Physics, and Sabine Hossenfelder’s Lost in Math leap to mind, and they have started a wider conversation. But is all of physics really in trouble, or just some of it? If you actually read these books, you’ll see they’re about so-called “fundamental” physics. Some other parts of physics are doing just fine, and I want to tell you about one. It’s called “condensed matter physics,” and it’s the study of solids and liquids. We are living in the golden age of condensed matter physics.

Everyone seems to be talking about the problems with physics: Peter Woit’s book Not Even Wrong, Lee Smolin’s The Trouble With Physics, and Sabine Hossenfelder’s Lost in Math leap to mind, and they have started a wider conversation. But is all of physics really in trouble, or just some of it? If you actually read these books, you’ll see they’re about so-called “fundamental” physics. Some other parts of physics are doing just fine, and I want to tell you about one. It’s called “condensed matter physics,” and it’s the study of solids and liquids. We are living in the golden age of condensed matter physics.