Category: Recommended Reading

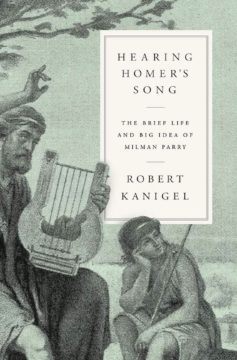

The Darwin of the Classics

Tim Riley at the LARB:

“The effects of oral states of consciousness,” Walter Ong wrote in his 1982 book Orality and Literacy, “are bizarre to the literate mind.” Parry theorized that, if he could find a find a culture where bards still practiced an oral tradition, singing songs as long as Homer’s (over 12,000 lines), he could prove the links between Homeric verse and Bosnian song that scholars had long been puzzling over. In his approach, Parry worked a different field with some of the same purpose Alan Lomax did in the American South during this same period, collecting a rural folk tradition in order to catalog the vast body of American song. The Muslim Slavs of Bosnia, where Parry focused his recording, were called “guslars,” and played a single-string instrument called the “gusle.”

“The effects of oral states of consciousness,” Walter Ong wrote in his 1982 book Orality and Literacy, “are bizarre to the literate mind.” Parry theorized that, if he could find a find a culture where bards still practiced an oral tradition, singing songs as long as Homer’s (over 12,000 lines), he could prove the links between Homeric verse and Bosnian song that scholars had long been puzzling over. In his approach, Parry worked a different field with some of the same purpose Alan Lomax did in the American South during this same period, collecting a rural folk tradition in order to catalog the vast body of American song. The Muslim Slavs of Bosnia, where Parry focused his recording, were called “guslars,” and played a single-string instrument called the “gusle.”

To help in his field research, Parry — working with Lord, who was then his graduate student — brought along some of the same bulky portable recording gear used by Leoš Janáček and Béla Bartók to record singers.

more here.

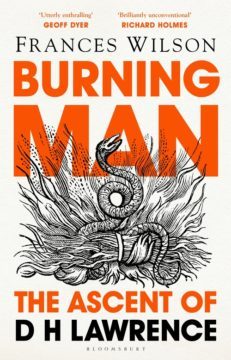

Burning Man: The Ascent of D H Lawrence

David Wheatley at Literary Review:

Beyond all this violent contrarianism, the Lawrence Wilson wishes to paint is a figure of ‘mysteries rather than certainties’. The ‘burning man’ of her title derives from a letter of 1913 in which Lawrence the would-be martyr for his art compares himself to his namesake saint, who famously embraced his martyrdom (death on a gridiron) to the point of proclaiming, ‘Turn me over brothers, I am done enough on this side.’ Wilson’s target is less a straightforward biography than a sifting of Lawrence’s legacy for what remains urgent and alive, the aim being to shed its infernal baggage in search of an abiding paradise. One threat to her Dante comparison is how remote from heaven Lawrence increasingly appears, his attachment to the physical world growing shriller the weaker his grip on it becomes. But these tensions are all part of the drama, not least where the question of sex is concerned. Sex in Lawrence must always be a full-on sacramental affair, but in everyday life he was uptight and prissy about being touched, unlike the more easy-going Frieda.

Beyond all this violent contrarianism, the Lawrence Wilson wishes to paint is a figure of ‘mysteries rather than certainties’. The ‘burning man’ of her title derives from a letter of 1913 in which Lawrence the would-be martyr for his art compares himself to his namesake saint, who famously embraced his martyrdom (death on a gridiron) to the point of proclaiming, ‘Turn me over brothers, I am done enough on this side.’ Wilson’s target is less a straightforward biography than a sifting of Lawrence’s legacy for what remains urgent and alive, the aim being to shed its infernal baggage in search of an abiding paradise. One threat to her Dante comparison is how remote from heaven Lawrence increasingly appears, his attachment to the physical world growing shriller the weaker his grip on it becomes. But these tensions are all part of the drama, not least where the question of sex is concerned. Sex in Lawrence must always be a full-on sacramental affair, but in everyday life he was uptight and prissy about being touched, unlike the more easy-going Frieda.

more here.

Tuesday, May 4, 2021

Adjunct Hell: The rise of a new kind of campus novel

Maggie Doherty in The Nation:

Not so long ago, there seemed to be something radical in rejecting the future. Looking back, it’s easy to see why. In the 1990s, history was over; the United States and capitalism had won. Strutting conservative televangelists and smug liberal technocrats took turns running the world. Globalization promised more of everything: more productivity, more innovation, more wealth. Economic prosperity and regressive moralism went hand in hand. The nuclear family was once again sacred, and non-normative sexuality remained stigmatized: Don’t ask, but also don’t tell. Conservatives—as well as some liberals—supported any policy that promised to protect children, born and unborn, so they might take advantage of the bright future that awaited them. Meritocracy was supposedly thriving, even as inequality prevailed everywhere.

Not so long ago, there seemed to be something radical in rejecting the future. Looking back, it’s easy to see why. In the 1990s, history was over; the United States and capitalism had won. Strutting conservative televangelists and smug liberal technocrats took turns running the world. Globalization promised more of everything: more productivity, more innovation, more wealth. Economic prosperity and regressive moralism went hand in hand. The nuclear family was once again sacred, and non-normative sexuality remained stigmatized: Don’t ask, but also don’t tell. Conservatives—as well as some liberals—supported any policy that promised to protect children, born and unborn, so they might take advantage of the bright future that awaited them. Meritocracy was supposedly thriving, even as inequality prevailed everywhere.

In response, a reasonable nihilism emerged in the era’s counterculture. If conservatives, and even some liberals, were “pro-life” and “focused on the family,” all in the name of a bountiful future provided to us by the end of the Cold War, then what positions should radicals take?

More here.

Sean Carrol’s Mindscape Podcast: Niall Ferguson on Histories, Networks, and Catastrophes

Sean Carroll in Preposterous Universe:

The world has gone through a tough time with the COVID-19 pandemic. Every catastrophic event is unique, but there are certain commonalities to how such crises play out in our modern interconnected world. Historian Niall Ferguson wrote a book from a couple of years ago, The Square and the Tower, that considered how an interplay between networks and hierarchies has shaped the history of the world. This analysis is directly relevant to how we deal with large-scale catastrophes, which is the subject of his new book, Doom: The Politics of Catastrophe. We talk about global culture as a complex system, and what it means for our ability to respond to crisis.

The world has gone through a tough time with the COVID-19 pandemic. Every catastrophic event is unique, but there are certain commonalities to how such crises play out in our modern interconnected world. Historian Niall Ferguson wrote a book from a couple of years ago, The Square and the Tower, that considered how an interplay between networks and hierarchies has shaped the history of the world. This analysis is directly relevant to how we deal with large-scale catastrophes, which is the subject of his new book, Doom: The Politics of Catastrophe. We talk about global culture as a complex system, and what it means for our ability to respond to crisis.

More here.

Jeffrey Sachs: Share the Intellectual Property on COVID-19

Jeffrey D. Sachs in Project Syndicate:

The governments of South Africa, India, and dozens of other developing countries are calling for the rights on intellectual property (IP), including vaccine patents, to be waived to accelerate the worldwide production of supplies to fight COVID-19. They are absolutely correct. IP for fighting COVID-19 should be waived, and indeed actively shared among scientists, companies, and nations.

The governments of South Africa, India, and dozens of other developing countries are calling for the rights on intellectual property (IP), including vaccine patents, to be waived to accelerate the worldwide production of supplies to fight COVID-19. They are absolutely correct. IP for fighting COVID-19 should be waived, and indeed actively shared among scientists, companies, and nations.

The pharmaceutical industry and the governments of several vaccine-producing countries, including the United States and the United Kingdom, as well as the European Commission, have been resisting the IP waiver, while 150 public leaders and experts have sent an open letter to US President Joe Biden in support of it. There is no longer any question about who is right. Given the surge of COVID-19 in several regions, most recently in India, the continuing emergence of new and deadly variants of the virus, and the inability of the current vaccine producers to keep pace with global needs, an IP waiver or its equivalent has become a practical urgent need as well as a moral imperative.

As a general principle, IP should not stand in the way of scaling up production to fight COVID-19 or any other public health emergency.

More here.

Freeman Dyson on meeting Ludwig Wittgenstein

Persuading the Body to Regenerate Its Limbs

Matthew Hutson in The New Yorker:

Each year, researchers from around the world gather at Neural Information Processing Systems, an artificial-intelligence conference, to discuss automated translation software, self-driving cars, and abstract mathematical questions. It was odd, therefore, when Michael Levin, a developmental biologist at Tufts University, gave a presentation at the 2018 conference, which was held in Montreal. Fifty-one, with light-green eyes and a dark beard that lend him a mischievous air, Levin studies how bodies grow, heal, and, in some cases, regenerate. He waited onstage while one of Facebook’s A.I. researchers introduced him, to a packed exhibition hall, as a specialist in “computation in the medium of living systems.”

Each year, researchers from around the world gather at Neural Information Processing Systems, an artificial-intelligence conference, to discuss automated translation software, self-driving cars, and abstract mathematical questions. It was odd, therefore, when Michael Levin, a developmental biologist at Tufts University, gave a presentation at the 2018 conference, which was held in Montreal. Fifty-one, with light-green eyes and a dark beard that lend him a mischievous air, Levin studies how bodies grow, heal, and, in some cases, regenerate. He waited onstage while one of Facebook’s A.I. researchers introduced him, to a packed exhibition hall, as a specialist in “computation in the medium of living systems.”

Levin began his talk, and a drawing of a worm appeared on the screen behind him. Some of the most important discoveries of his career hinge on the planarian—a type of flatworm about two centimetres long that, under a microscope, resembles a cartoon of a cross-eyed phallus. Levin is interested in the planarian because, if you cut off its head, it grows a new one; simultaneously, its severed head grows a new tail. Researchers have discovered that no matter how many pieces you cut a planarian into—the record is two hundred and seventy-nine—you will get as many new worms. Somehow, each part knows what’s missing and builds it anew. What Levin showed his audience was something even more striking: a video of a two-headed planarian. He had cut off the worm’s tail, then persuaded the organism to grow a second head in its place. No matter how many times the extra head was cut off, it grew back.

The most astonishing part was that Levin hadn’t touched the planarian’s genome. Instead, he’d changed the electrical signals among the worm’s cells. Levin explained that, by altering this electric patterning, he’d revised the organism’s “memory” of what it was supposed to look like. In essence, he’d reprogrammed the worm’s body—and, if he wanted to, he could switch it back.

More here.

Angels of History

Andy Battle in Boston Review:

I remember the first time I ever saw a ghost. I was tiptoeing through the remnants of a burnt-out row house in Washington, D.C., in one of the neighborhoods where, in the 1990s, one could still discern the architectural scars from the urban rebellions meant to avenge the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., thirty years before.

I remember the first time I ever saw a ghost. I was tiptoeing through the remnants of a burnt-out row house in Washington, D.C., in one of the neighborhoods where, in the 1990s, one could still discern the architectural scars from the urban rebellions meant to avenge the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., thirty years before.

Stepping gingerly over charred beams, scanning the scattered furniture, my eye landed on a toy—a doll, lying relatively unscathed amidst the debris. In an instant I saw the house as it had been, in its unburnt serenity. A family had lived there. Children grew up there. Psyches, fortunes, relationships germinated in this place. Fortunes that were not mine, lives given their shape by the monstrous hammers of class and race in America. The image I saw—the past I made—awakened questions. What happened to these people? Where had they gone? Why were there so many houses like this one, abandoned and empty in a city where so many lacked homes? That was probably the day I decided to become a historian.

Historians live a good deal of their lives in the past. In doing so, one realizes how many ways there are to inhabit it. The past can serve variously as wellspring, shelter, or cage. There are many pasts to live, as well—personal pasts and political pasts, individual and collective ones. Oftentimes we live them all at once.

More here.

Tuesday Poem

Sunday School Circa 1950

“Who made you?” was always

The question

The answer was always

“God.”

Well, there we stood

Tree feet high

Head bowed

Leaning into

Bosoms.

Now

I no longer recall

The Catechism

Or brood on the genesis

Of life

No.

I ponder the exchange

Itself

And salvage mostly

the leaning.

by Alice Walker

from Her Blue Body Everything we Know

Harvest Books, 1991

Buckley Interviews Borges (!)

Memories of Murder: In the Killing Jar

Ed Park at The Current:

In September 2019, about halfway between claiming the Palme d’Or at Cannes in May and earning multiple Oscar nominations in January 2020, Bong Joon Ho’s Parasite was briefly upstaged by a movie from the director’s past. His second feature, Memories of Murder (2003), had grappled with South Korea’s most chilling cold case: a spree in which ten women and girls were raped and murdered near Hwaseong, about twenty-six miles south of Seoul. (Song Kang Ho, a star of Parasite, plays one of the police detectives obsessed with nabbing the culprit.) According to a May 2020 CNN story, “About 226,000 people lived in the area, scattered among a number of villages between forested hills and rice paddies,” in a region that previously had reported “no real crime to speak of.” The slaughter began in 1986 and continued for five years. A suspect was jailed for one of the crimes in 1989 and released on parole in 2009; the others, however, went unanswered. The specter of what have been called Korea’s first serial killings profoundly spooked the nation: Police investigated over 20,000 people, some even after the statute of limitations expired in 2006. Over two million “man-days” were devoted to the case—nearly 5,500 years, longer by a millennium than Korea itself has been around. You could think of the investigation as an entire civilization built around a singular depravity.

In September 2019, about halfway between claiming the Palme d’Or at Cannes in May and earning multiple Oscar nominations in January 2020, Bong Joon Ho’s Parasite was briefly upstaged by a movie from the director’s past. His second feature, Memories of Murder (2003), had grappled with South Korea’s most chilling cold case: a spree in which ten women and girls were raped and murdered near Hwaseong, about twenty-six miles south of Seoul. (Song Kang Ho, a star of Parasite, plays one of the police detectives obsessed with nabbing the culprit.) According to a May 2020 CNN story, “About 226,000 people lived in the area, scattered among a number of villages between forested hills and rice paddies,” in a region that previously had reported “no real crime to speak of.” The slaughter began in 1986 and continued for five years. A suspect was jailed for one of the crimes in 1989 and released on parole in 2009; the others, however, went unanswered. The specter of what have been called Korea’s first serial killings profoundly spooked the nation: Police investigated over 20,000 people, some even after the statute of limitations expired in 2006. Over two million “man-days” were devoted to the case—nearly 5,500 years, longer by a millennium than Korea itself has been around. You could think of the investigation as an entire civilization built around a singular depravity.

more here.

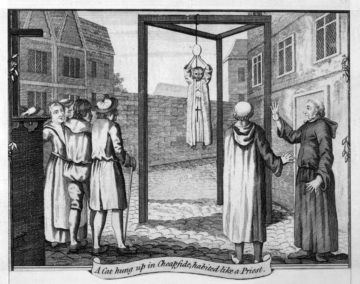

Animals On Trial

Jeffrey Kastner at Cabinet Magazine:

The history of animals in the legal system sketched by Evans is rich and resonant; it provokes profound questions about the evolution of jurisprudential procedure, social and religious organization and notions of culpability and punishment, and fundamental philosophical questions regarding the place of man within the natural order. In Evans’s narrative, all creatures great and small have their moment before the bench. Grasshoppers and mice; flies and caterpillars; roosters, weevils, sheep, horses, turtle doves—each takes its turn in the dock, in many cases represented by counsel; each meets a fate in accordance with precedent, delivered by a duly appointed official.2 Yet for all the import (both practical and metaphysical) of the issues on which they touch, in their details the tales Evans spins often seem to suggest nothing so much as a series of lost Monty Python sketches—from the story of the distinguished 16th-century French jurist Bartholomew Chassenée, who was said to have made his not inconsiderable reputation for creative argument and persistent advocacy on the strength of his representation of “some rats, which had been put on trial before the ecclesiastical court of Autun on the charge of having feloniously eaten up and wantonly destroyed the barley crop of that province,”3 to the 1750 trial in Vanvres of a “she-ass, taken in the act of coition” with one Jacques Ferron. In the latter case, the unfortunate quadruped was sentenced to death along with her seducer and appeared headed for the gallows until a last minute reprieve was issued on behalf of the parish priest and citizenry of the village, who had “signed a certificate stating that they had known the said she-ass for four years, and that she had always shown herself to be virtuous and well-behaved both at home and abroad and had never given occasion of scandal to anyone…” Nudge, nudge; say no more.

The history of animals in the legal system sketched by Evans is rich and resonant; it provokes profound questions about the evolution of jurisprudential procedure, social and religious organization and notions of culpability and punishment, and fundamental philosophical questions regarding the place of man within the natural order. In Evans’s narrative, all creatures great and small have their moment before the bench. Grasshoppers and mice; flies and caterpillars; roosters, weevils, sheep, horses, turtle doves—each takes its turn in the dock, in many cases represented by counsel; each meets a fate in accordance with precedent, delivered by a duly appointed official.2 Yet for all the import (both practical and metaphysical) of the issues on which they touch, in their details the tales Evans spins often seem to suggest nothing so much as a series of lost Monty Python sketches—from the story of the distinguished 16th-century French jurist Bartholomew Chassenée, who was said to have made his not inconsiderable reputation for creative argument and persistent advocacy on the strength of his representation of “some rats, which had been put on trial before the ecclesiastical court of Autun on the charge of having feloniously eaten up and wantonly destroyed the barley crop of that province,”3 to the 1750 trial in Vanvres of a “she-ass, taken in the act of coition” with one Jacques Ferron. In the latter case, the unfortunate quadruped was sentenced to death along with her seducer and appeared headed for the gallows until a last minute reprieve was issued on behalf of the parish priest and citizenry of the village, who had “signed a certificate stating that they had known the said she-ass for four years, and that she had always shown herself to be virtuous and well-behaved both at home and abroad and had never given occasion of scandal to anyone…” Nudge, nudge; say no more.

more here.

Sunday, May 2, 2021

The Neoliberal Fantasy at the Heart of ‘Nomadland’

Arun Gupta and Michelle Fawcett in In These Times:

In the real world, many nomads desperately want a house. One admits “there is not so much difference between” the van dweller and the homeless person. By making Fern’s story one of personal responsibility and freedom, the movie erases the causes of the nomads’ economic pain. Individual suffering becomes individual triumph; the crisis of capitalism is also the solution.

In the real world, many nomads desperately want a house. One admits “there is not so much difference between” the van dweller and the homeless person. By making Fern’s story one of personal responsibility and freedom, the movie erases the causes of the nomads’ economic pain. Individual suffering becomes individual triumph; the crisis of capitalism is also the solution.

If nomads are refugees from the subprime mortgage crash, the perilous landscape they travel was shaped by the tectonic social upheavals that began in the Reagan era. Fern’s exile from Empire, owned by a gypsum-mining company, is a nod to the deindustrialization that accelerated under Reagan. The landscape of permanent homelessness that nomads exist in was born of Reagan gutting funds for social welfare and cities. Nomads trade leads on jobs flipping burgers at tourist spots and cleaning toilets in national parks like they trade can openers for potholders at desert meetups. Gig work is another Reagan-era legacy; his assault on organized labor made it easier for corporations to expand contingent labor.

In the film, Amazon becomes as natural as the land. Wide-angle shots of the Amazon warehouse make it appear to rise up like the mountains in the Nevada desert. It is a neutral feature on the terrain that one can only navigate, not change.

More here.

How to Rewrite the Laws of Physics in the Language of Impossibility

Amanda Gefter in Quanta:

They say that in art, constraints lead to creativity. The same seems to be true of the universe. By placing limits on nature, the laws of physics squeeze out reality’s most fantastical creations. Limit light’s speed, and suddenly space can shrink, time can slow. Limit the ability to divide energy into infinitely small units, and the full weirdness of quantum mechanics blossoms. “Declaring something impossible leads to more things being possible,” writes the physicist Chiara Marletto. “Bizarre as it may seem, it is commonplace in quantum physics.”

They say that in art, constraints lead to creativity. The same seems to be true of the universe. By placing limits on nature, the laws of physics squeeze out reality’s most fantastical creations. Limit light’s speed, and suddenly space can shrink, time can slow. Limit the ability to divide energy into infinitely small units, and the full weirdness of quantum mechanics blossoms. “Declaring something impossible leads to more things being possible,” writes the physicist Chiara Marletto. “Bizarre as it may seem, it is commonplace in quantum physics.”

Marletto grew up in Turin, in northern Italy, and studied physical engineering and theoretical physics before completing her doctorate at the University of Oxford, where she became interested in quantum information and theoretical biology. But her life changed when she attended a talk by David Deutsch, another Oxford physicist and a pioneer in the field of quantum computation. It was about what he claimed was a radical new theory of explanations. It was called constructor theory, and according to Deutsch it would serve as a kind of meta-theory more fundamental than even our most foundational physics — deeper than general relativity, subtler than quantum mechanics. To call it ambitious would be a massive understatement.

More here.

How the N-Word Became Unsayable

John McWhorter in the New York Times:

This article contains obscenities and racial slurs, fully spelled out. Ezekiel Kweku, the Opinion politics editor, and Kathleen Kingsbury, the Opinion editor, wrote about how and why we came to the decision to publish these words in Friday’s edition of the Opinion Today newsletter.

This article contains obscenities and racial slurs, fully spelled out. Ezekiel Kweku, the Opinion politics editor, and Kathleen Kingsbury, the Opinion editor, wrote about how and why we came to the decision to publish these words in Friday’s edition of the Opinion Today newsletter.

In 1934, Allen Walker Read, an etymologist and lexicographer, laid out the history of the word that, then, had “the deepest stigma of any in the language.” In the entire article, in line with the strength of the taboo he was referring to, he never actually wrote the word itself. The obscenity to which he referred, “fuck,” though not used in polite company (or, typically, in this newspaper), is no longer verboten. These days, there are two other words that an American writer would treat as Mr. Read did. One is “cunt,” and the other is “nigger.” The latter, though, has become more than a slur. It has become taboo.

Just writing the word here, I sense myself as pushing the envelope, even though I am Black — and feel a need to state that for the sake of clarity and concision, I will be writing the word freely, rather than “the N-word.” I will not use the word gratuitously, but that will nevertheless leave a great many times I do spell it out, love it though I shall not.

More here.

When Men Behave Badly: The Hidden Roots of Sexual Deception, Harassment, and Assault

Rob Henderson in Quillette:

Professor David M. Buss, a leading evolutionary psychologist, states in the introduction of his fascinating new book that it “uncovers the hidden roots of sexual conflict.” Though the book focuses on male misbehavior, it also contains a broad and fascinating overview of mating psychology.

Professor David M. Buss, a leading evolutionary psychologist, states in the introduction of his fascinating new book that it “uncovers the hidden roots of sexual conflict.” Though the book focuses on male misbehavior, it also contains a broad and fascinating overview of mating psychology.

Sex, as defined by biologists, is indicated by the size of our gametes. Males have smaller gametes (sperm) and females have larger gametes (eggs). Broadly speaking, women and men had conflicting interests in the ancestral environment. Women were more vulnerable than men. And women took on far more risk when having sex, including pregnancy, which was perilous in an environment without modern technology. In addition to the physical costs, in the final stages of pregnancy, women must also obtain extra calories. According to Britain’s Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, pregnant women in their final trimester require an additional 200 calories per day, or 18,000 calories more in total than they otherwise would have required. This surplus was not easy to obtain for our ancestors. Men, in contrast, did not face the same level of sexual risk.

More here.

Christa Ludwig (1928 – 2021)

Jill Corey (1935 – 2021)

Bob Fass (1933 – 2021)