Isabella Weber in Phenomenal World:

Isabella Weber in Phenomenal World:

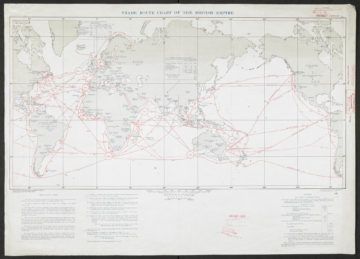

During the first era of globalization (1870–1913), the global division of labor was stark. Britain and other Western nations largely produced manufactured goods, but they also exported a whole range of temperate agricultural goods like wheat, beef and barley. Elsewhere in the European colonial empires, products like cotton, cocoa and coffee were exported, often at very low prices and sometimes with forced labor, to sate a growing demand in the global economic core for tropical luxuries. More than a century has passed since World War I heralded the collapse of this world order. Today, the globalization wave that has shaped the world since the 1980s is ebbing.

What is the legacy of the First Globalization of the late nineteenth- and early twentieth-centuries on the economic fortunes of countries during the Second Globalization? To what extent have countries’ positions in the international economic order been persistent across the two globalizations, with some trapped at the bottom and others comfortably on top?

Long-term development trajectories are commonly explained through the convergence hypothesis. Derived from neoclassical growth theory, it states that “initial conditions have no implications for the long-run distribution of per capita income.” The hypothesis suggests that history has no persistent bearing on countries’ relative wealth: if left to the laws of the market, poorer countries are expected to catch up by outperforming richer countries in their rates of economic growth. However, the convergence hypothesis is not backed by empirical evidence—extensive testing has not heralded the results that standard growth theory would expect. In an effort to elucidate these findings, a quickly growing “persistence literature” has proposed a range of explanations for why countries’ relative wealth today is historically rooted in institutional quality (referring in this case to property rights regimes and liberal representative democracy), culture, religion, geography, or even genetics.

More here.

Maria Bustillos in Eater:

Maria Bustillos in Eater: Anthony Comstock may be the only man in American history whose lobbying efforts yielded not only the exact federal law he wanted but the privilege of enforcing it to his liking for four decades. Given that Comstock never held elected office and that the highest appointed position he occupied in government was special agent of the Post Office, this was an extraordinary achievement—and a reminder of the ways that zealots have sometimes slipped past the sentries of American democracy to create a reality that the rest of us must live in. Comstock was an anti-vice crusader who worried about many of the things that Americans of a similar moral and religious cast worried about in the late nineteenth century: the rise of the so-called sporting press, which specialized in randy gossip and user guides to local brothels; the phenomenon of young men and women set loose in big cities, living, unsupervised, in cheap rooming houses; the enervating effects of masturbation; the ravages of venereal disease; the easy availability of contraceptives, such as condoms and pessaries, and of abortifacients, dispensed by druggists or administered by midwives. But Comstock railed against all these things more passionately than most of his contemporaries did, and far more effectively.

Anthony Comstock may be the only man in American history whose lobbying efforts yielded not only the exact federal law he wanted but the privilege of enforcing it to his liking for four decades. Given that Comstock never held elected office and that the highest appointed position he occupied in government was special agent of the Post Office, this was an extraordinary achievement—and a reminder of the ways that zealots have sometimes slipped past the sentries of American democracy to create a reality that the rest of us must live in. Comstock was an anti-vice crusader who worried about many of the things that Americans of a similar moral and religious cast worried about in the late nineteenth century: the rise of the so-called sporting press, which specialized in randy gossip and user guides to local brothels; the phenomenon of young men and women set loose in big cities, living, unsupervised, in cheap rooming houses; the enervating effects of masturbation; the ravages of venereal disease; the easy availability of contraceptives, such as condoms and pessaries, and of abortifacients, dispensed by druggists or administered by midwives. But Comstock railed against all these things more passionately than most of his contemporaries did, and far more effectively. Y

Y Every era gets the Gesamtkunstwerk it deserves. In Richard Wagner’s 1849 essay, The Artwork of the Future, the German composer conceives theater as the ideal site for the reintegration of dance, tone, and poetry, which had been separated out after their original unity in Greek drama. Architecture, too, was to be incorporated into the new unified mega-art, as the art of framing the total theater staged within its edifice. And there is drama too, which already on its own, Wagner thinks, is a sort of “conjoint” totality, “since it can only be at hand in all its possible fullness, when in it each separate branch of art is at hand in it in its own utmost fullness.”

Every era gets the Gesamtkunstwerk it deserves. In Richard Wagner’s 1849 essay, The Artwork of the Future, the German composer conceives theater as the ideal site for the reintegration of dance, tone, and poetry, which had been separated out after their original unity in Greek drama. Architecture, too, was to be incorporated into the new unified mega-art, as the art of framing the total theater staged within its edifice. And there is drama too, which already on its own, Wagner thinks, is a sort of “conjoint” totality, “since it can only be at hand in all its possible fullness, when in it each separate branch of art is at hand in it in its own utmost fullness.” Since first appearing in India in late 2020, the Delta variant of SARS-CoV-2 has become the predominant strain in much of the world. Researchers might now know why Delta has been so successful: people infected with it produce far more virus than do those infected with the original version of SARS-CoV-2, making it very easy to spread.

Since first appearing in India in late 2020, the Delta variant of SARS-CoV-2 has become the predominant strain in much of the world. Researchers might now know why Delta has been so successful: people infected with it produce far more virus than do those infected with the original version of SARS-CoV-2, making it very easy to spread. As someone prone to panic attacks and spectacularly inept at dealing with adversity in life, I found it immensely comforting to have two Cuban feet in my face all night. I was also well aware that my visible fragility was less than endearing in a detention situation created in large part by my own nation – a situation from which, thanks to my passport privilege, I would inevitably be extricated with relatively minimal suffering.

As someone prone to panic attacks and spectacularly inept at dealing with adversity in life, I found it immensely comforting to have two Cuban feet in my face all night. I was also well aware that my visible fragility was less than endearing in a detention situation created in large part by my own nation – a situation from which, thanks to my passport privilege, I would inevitably be extricated with relatively minimal suffering. E

E Greeks who have met Argentines, and Argentines who travel to Greece, often wax on strange parallels — on the discovery of inexplicable and unexpected similarities between peoples, like stumbling upon an enchanted mirror that mocks.

Greeks who have met Argentines, and Argentines who travel to Greece, often wax on strange parallels — on the discovery of inexplicable and unexpected similarities between peoples, like stumbling upon an enchanted mirror that mocks. MANIFESTO IS THE FORM THAT EATS AND REPEATS ITSELF. Always layered and paradoxical, it comes disguised as nakedness, directness, aggression. An artwork aspiring to be a speech act—like a threat, a promise, a joke, a spell, a dare. You can’t help but thrill to language that imagines it can get something done. You also can’t help noticing the similar demands and condemnations that ring out across the decades and the centuries—something will be swept away or conjured into being, and it must happen right this moment. While appearing to invent itself ex nihilo, the manifesto grabs whatever magpie trinkets it can find, including those that drew the eye in earlier manifestos. This is a form that asks readers to suspend their disbelief, and so like any piece of theater, it trades on its own vulnerability, invites our complicity, as if only the quality of our attention protects it from reality’s brutal puncture. A manifesto is a public declaration of intent, a laying out of the writer’s views (shared, it’s implied, by at least some vanguard “we”) on how things are and how they should be altered. Once the province of institutional authority, decrees from church or state, the manifesto later flowered as a mode of presumption and dissent. You assume the writer stands outside the halls of power (or else, occasionally, chooses to pose and speak from there). Today the US government, for example, does not issue manifestos, lest it sound both hectoring and weak. The manifesto is inherently quixotic—spoiling for a fight it’s unlikely to win, insisting on an outcome it lacks the authority to ensure.

MANIFESTO IS THE FORM THAT EATS AND REPEATS ITSELF. Always layered and paradoxical, it comes disguised as nakedness, directness, aggression. An artwork aspiring to be a speech act—like a threat, a promise, a joke, a spell, a dare. You can’t help but thrill to language that imagines it can get something done. You also can’t help noticing the similar demands and condemnations that ring out across the decades and the centuries—something will be swept away or conjured into being, and it must happen right this moment. While appearing to invent itself ex nihilo, the manifesto grabs whatever magpie trinkets it can find, including those that drew the eye in earlier manifestos. This is a form that asks readers to suspend their disbelief, and so like any piece of theater, it trades on its own vulnerability, invites our complicity, as if only the quality of our attention protects it from reality’s brutal puncture. A manifesto is a public declaration of intent, a laying out of the writer’s views (shared, it’s implied, by at least some vanguard “we”) on how things are and how they should be altered. Once the province of institutional authority, decrees from church or state, the manifesto later flowered as a mode of presumption and dissent. You assume the writer stands outside the halls of power (or else, occasionally, chooses to pose and speak from there). Today the US government, for example, does not issue manifestos, lest it sound both hectoring and weak. The manifesto is inherently quixotic—spoiling for a fight it’s unlikely to win, insisting on an outcome it lacks the authority to ensure. Maeve Wallace has studied maternal health in the United States for more than a decade, and a grim statistic haunts her. Five years ago, she published a study showing that being pregnant or recently having had a baby nearly doubles a woman’s risk of being killed

Maeve Wallace has studied maternal health in the United States for more than a decade, and a grim statistic haunts her. Five years ago, she published a study showing that being pregnant or recently having had a baby nearly doubles a woman’s risk of being killed By June 1956, at the end of my first year as a research student, I had a set of chapters that looked as if they could form a dissertation. A substantial number of economists at various universities were work ing then on different ways of choosing between techniques of production. Some were particularly focused on maximising the total value of the output produced, whereas others wanted to maximise the surplus that was generated, and there were also some profit maximisers.

By June 1956, at the end of my first year as a research student, I had a set of chapters that looked as if they could form a dissertation. A substantial number of economists at various universities were work ing then on different ways of choosing between techniques of production. Some were particularly focused on maximising the total value of the output produced, whereas others wanted to maximise the surplus that was generated, and there were also some profit maximisers. Researchers from the University of Oxford and their partners have today reported findings from a Phase IIb trial of a candidate malaria vaccine, R21/Matrix-M, which demonstrated high-level efficacy of 77% over 12-months of follow-up.

Researchers from the University of Oxford and their partners have today reported findings from a Phase IIb trial of a candidate malaria vaccine, R21/Matrix-M, which demonstrated high-level efficacy of 77% over 12-months of follow-up. Sex and analytic philosophy are not promising bedfellows. But when it comes to feminist philosophy, it is no mere pun to say that sex is where the action is. The revival of this neglected feminist concern is principally owed to Amia Srinivasan, the 36-year-old star of Oxford philosophy and Chichele Professor of Social and Political Theory at All Souls College. Srinivasan began her career making influential contributions to formal epistemology and shot up the academic rungs; she has since found a public audience as a critic and essayist of remarkable precision and range. In her new essay collection, The Right to Sex, Srinivasan writes about consent, pornography and the ideological shaping of desire, attempting “to remake the political critique of sex for the 21st century.” Here, the political isn’t just personal; it’s intimate.

Sex and analytic philosophy are not promising bedfellows. But when it comes to feminist philosophy, it is no mere pun to say that sex is where the action is. The revival of this neglected feminist concern is principally owed to Amia Srinivasan, the 36-year-old star of Oxford philosophy and Chichele Professor of Social and Political Theory at All Souls College. Srinivasan began her career making influential contributions to formal epistemology and shot up the academic rungs; she has since found a public audience as a critic and essayist of remarkable precision and range. In her new essay collection, The Right to Sex, Srinivasan writes about consent, pornography and the ideological shaping of desire, attempting “to remake the political critique of sex for the 21st century.” Here, the political isn’t just personal; it’s intimate.