Costică Brădăţan at The American Scholar:

“Raised in Britain as a post-Christian secular humanist and trained in Asia as a Tibetan and Zen Buddhist monk,” Stephen Batchelor writes at the end of his book, Buddha, Socrates, and Us, “I find that I can no longer identify exclusively with either a Western or an Eastern tradition.” Decades of dwelling in these traditions—each with its own intellectual, spiritual, and philosophical riches—have left him strangely homeless. Far from making him unhappy, though, this state of existential homelessness has given Batchelor access to what he sees as a higher life. For, while “unsettling and disorienting” at times, such “spaces of uncertainty seem far richer in creative possibilities, more open to leading a life of wonder, imagination, and action.”

“Raised in Britain as a post-Christian secular humanist and trained in Asia as a Tibetan and Zen Buddhist monk,” Stephen Batchelor writes at the end of his book, Buddha, Socrates, and Us, “I find that I can no longer identify exclusively with either a Western or an Eastern tradition.” Decades of dwelling in these traditions—each with its own intellectual, spiritual, and philosophical riches—have left him strangely homeless. Far from making him unhappy, though, this state of existential homelessness has given Batchelor access to what he sees as a higher life. For, while “unsettling and disorienting” at times, such “spaces of uncertainty seem far richer in creative possibilities, more open to leading a life of wonder, imagination, and action.”

At its core, Batchelor’s Buddha, Socrates, and Us may be read as a response to a simple, yet important observation: everything in life tends to fall into patterns, to settle into habits and routines. Not even matters of the spirit—religion and philosophy, beliefs and ideas, thinking and writing—seem to escape this fate. Such mindless repetition makes our lives easier and more comfortable, at least on the outside, but to do things mechanically and unthinkingly is to invite emptiness and meaninglessness into our existence.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

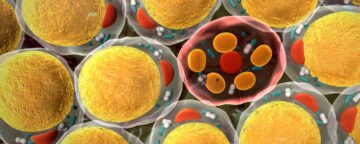

For some three billion years, unicellular organisms ruled Earth. Then, around one billion years ago, a new chapter of life began. Early attempts at team living began to stick, paving the way for the evolution of complex organisms, including animals, plants and fungi. Across all known life, the move to multicellularity happened at least 40 times, suggests one study1. But, in animals, it seems to have occurred only once.

For some three billion years, unicellular organisms ruled Earth. Then, around one billion years ago, a new chapter of life began. Early attempts at team living began to stick, paving the way for the evolution of complex organisms, including animals, plants and fungi. Across all known life, the move to multicellularity happened at least 40 times, suggests one study1. But, in animals, it seems to have occurred only once.

Made at the high point of Kline, de Kooning, and Pollock, Andy Warhol’s “Campbell’s Soup Cans” was a poke in the eye of abstract expressionism. Not only was it blatantly mimetic, but it was being blatantly mimetic with a mundane commercial product found in every supermarket and corner grocery store in America. When people think of repetition in painting, they probably think first of these iconic soup cans.

Made at the high point of Kline, de Kooning, and Pollock, Andy Warhol’s “Campbell’s Soup Cans” was a poke in the eye of abstract expressionism. Not only was it blatantly mimetic, but it was being blatantly mimetic with a mundane commercial product found in every supermarket and corner grocery store in America. When people think of repetition in painting, they probably think first of these iconic soup cans. Automating routine tasks expands possibilities. Before automatic differentiation, deep learning practitioners derived and implemented gradients by hand for each model family, a laborious and error-prone process. When Theano and its successors automated this mathematical labor, they transformed neural networks from a specialized practice into a broadly accessible discipline. This unlock, combined with massive datasets and GPU computing, catalyzed the deep learning revolution.

Automating routine tasks expands possibilities. Before automatic differentiation, deep learning practitioners derived and implemented gradients by hand for each model family, a laborious and error-prone process. When Theano and its successors automated this mathematical labor, they transformed neural networks from a specialized practice into a broadly accessible discipline. This unlock, combined with massive datasets and GPU computing, catalyzed the deep learning revolution. Following the 2008 financial collapse, US capitalism changed forever. While the banks were bailed out, more and more workers with secure, high-quality employment found themselves among the “untouchables” scrounging for a living in short-term, low-paid, dead-end jobs. Whereas Reagan and the Bushes won elections because secure proletarians voted for them and untouchables were too disheartened to vote at all, Trump won by rallying the untouchables, who now included a growing number of hitherto secure proletarians.

Following the 2008 financial collapse, US capitalism changed forever. While the banks were bailed out, more and more workers with secure, high-quality employment found themselves among the “untouchables” scrounging for a living in short-term, low-paid, dead-end jobs. Whereas Reagan and the Bushes won elections because secure proletarians voted for them and untouchables were too disheartened to vote at all, Trump won by rallying the untouchables, who now included a growing number of hitherto secure proletarians. What transpired next was a kind of Dionysian rural festival where performers hung carcasses and living bodies, animal and human, losing themselves in pouring, smearing, splashing—actions Nitsch had developed for years. Mythical figures became crucial scaffolds alongside Christian elements like garments, foot-washing, a grail, and the cross. Odysseus and Parsifal recurred as structural motifs that framed the choreography, scent, sound, and sacrificial acts: Odysseus as an emblem of the wandering heroic subject who must cross the threshold into chaos, the way the performers descend into a forest of flesh. Performers took their time carrying wooden structures for which human and animal bodies were used as embellishment. Huge white cloths were stretched, spattered with bright-red animal blood next to lilies, slaughtered flesh, and the symbolically crucified, tied-up human body.

What transpired next was a kind of Dionysian rural festival where performers hung carcasses and living bodies, animal and human, losing themselves in pouring, smearing, splashing—actions Nitsch had developed for years. Mythical figures became crucial scaffolds alongside Christian elements like garments, foot-washing, a grail, and the cross. Odysseus and Parsifal recurred as structural motifs that framed the choreography, scent, sound, and sacrificial acts: Odysseus as an emblem of the wandering heroic subject who must cross the threshold into chaos, the way the performers descend into a forest of flesh. Performers took their time carrying wooden structures for which human and animal bodies were used as embellishment. Huge white cloths were stretched, spattered with bright-red animal blood next to lilies, slaughtered flesh, and the symbolically crucified, tied-up human body. “Raised in Britain as a post-Christian secular humanist and trained in Asia as a Tibetan and Zen Buddhist monk,” Stephen Batchelor writes at the end of his book, Buddha, Socrates, and Us, “I find that I can no longer identify exclusively with either a Western or an Eastern tradition.” Decades of dwelling in these traditions—each with its own intellectual, spiritual, and philosophical riches—have left him strangely homeless. Far from making him unhappy, though, this state of existential homelessness has given Batchelor access to what he sees as a higher life. For, while “unsettling and disorienting” at times, such “spaces of uncertainty seem far richer in creative possibilities, more open to leading a life of wonder, imagination, and action.”

“Raised in Britain as a post-Christian secular humanist and trained in Asia as a Tibetan and Zen Buddhist monk,” Stephen Batchelor writes at the end of his book, Buddha, Socrates, and Us, “I find that I can no longer identify exclusively with either a Western or an Eastern tradition.” Decades of dwelling in these traditions—each with its own intellectual, spiritual, and philosophical riches—have left him strangely homeless. Far from making him unhappy, though, this state of existential homelessness has given Batchelor access to what he sees as a higher life. For, while “unsettling and disorienting” at times, such “spaces of uncertainty seem far richer in creative possibilities, more open to leading a life of wonder, imagination, and action.” Apples and bananas may be some of America’s favorite fruits. But nutrition experts say that kiwis deserve a spot in your shopping cart. These brown, fuzzy fruits with green, yellow or even red flesh are packed with beneficial nutrients like fiber and vitamin C. And on TikTok, wellness influencers rave about their

Apples and bananas may be some of America’s favorite fruits. But nutrition experts say that kiwis deserve a spot in your shopping cart. These brown, fuzzy fruits with green, yellow or even red flesh are packed with beneficial nutrients like fiber and vitamin C. And on TikTok, wellness influencers rave about their  The US sits atop vast reserves of fossil fuels, which have underpinned its national prosperity for decades. They have lit cities, powered factories, stimulated postwar job growth, and forged

The US sits atop vast reserves of fossil fuels, which have underpinned its national prosperity for decades. They have lit cities, powered factories, stimulated postwar job growth, and forged  For those contemplating mass casualties, biotoxins like ricin are easy to produce. But delivering them effectively is difficult, requiring specialized techniques like aerosolization. Conversely for chemical warfare agents like sarin, synthesis (because of restricted precursors) has traditionally been the hard part, even if delivering them

For those contemplating mass casualties, biotoxins like ricin are easy to produce. But delivering them effectively is difficult, requiring specialized techniques like aerosolization. Conversely for chemical warfare agents like sarin, synthesis (because of restricted precursors) has traditionally been the hard part, even if delivering them  Recent assaults on DEI from the right have caused people who care about a diverse, inclusive America to circle the wagons against

Recent assaults on DEI from the right have caused people who care about a diverse, inclusive America to circle the wagons against Consider Friedrich Nietzsche, one of the first thinkers of the

Consider Friedrich Nietzsche, one of the first thinkers of the  P

P Born in 1720, White was educated at the University of Oxford, UK, before settling at The Wakes — his family home in Selborne, UK — in around 1757. Then, from 1768, he worked for 25 years on his Naturalist’s Journal, a columnar diary in which each page covered a week of observations on fruit and vegetable experiments, local creatures and weather conditions. White’s daily entries in Selborne were often haiku-like in their simplicity. He described “vast rocklike, distant clouds” or simply stated “Bees swarm much. Sheep are shorn.”

Born in 1720, White was educated at the University of Oxford, UK, before settling at The Wakes — his family home in Selborne, UK — in around 1757. Then, from 1768, he worked for 25 years on his Naturalist’s Journal, a columnar diary in which each page covered a week of observations on fruit and vegetable experiments, local creatures and weather conditions. White’s daily entries in Selborne were often haiku-like in their simplicity. He described “vast rocklike, distant clouds” or simply stated “Bees swarm much. Sheep are shorn.”