Elizabeth Lund in The Christian Science Monitor:

During her lifetime, Elizabeth Barrett Browning (1806-61) was widely regarded as Britain’s best female poet. Her groundbreaking work helped sway public opinion against slavery and child labor and changed the direction of English-language poetry for generations. Yet within 70 years of her death, Barrett Browning was no longer viewed as an international literary superstar but as an invalid with a small, couch-bound life. By the 1970s, critics described her as lacking the talent of her husband, Robert Browning, and hindering his writing. Fiona Sampson challenges those views in “Two-Way Mirror: The Life of Elizabeth Barrett Browning,” the first new biography of the poet in more than 30 years. Sampson, whose works include the critically acclaimed biography “In Search of Mary Shelley,” reframes Barrett Browning’s reputation by highlighting her development as a writer despite the many restrictions she faced in Victorian society.

During her lifetime, Elizabeth Barrett Browning (1806-61) was widely regarded as Britain’s best female poet. Her groundbreaking work helped sway public opinion against slavery and child labor and changed the direction of English-language poetry for generations. Yet within 70 years of her death, Barrett Browning was no longer viewed as an international literary superstar but as an invalid with a small, couch-bound life. By the 1970s, critics described her as lacking the talent of her husband, Robert Browning, and hindering his writing. Fiona Sampson challenges those views in “Two-Way Mirror: The Life of Elizabeth Barrett Browning,” the first new biography of the poet in more than 30 years. Sampson, whose works include the critically acclaimed biography “In Search of Mary Shelley,” reframes Barrett Browning’s reputation by highlighting her development as a writer despite the many restrictions she faced in Victorian society.

As a child, Elizabeth Barrett – called “Ba” by her parents and 11 siblings – defied expectations. She penned her first poems at the age of 8 and began reading Homer, Shakespeare, and Milton, guided by her mother. For her 14th birthday, her father paid to have 50 copies printed of “The Battle of Marathon,” a 1,500-line moral tale she wrote in heroic couplets.

Her life changed profoundly a year later when she developed an illness that doctors tried to treat with prolonged bed rest and dangerous remedies, including opium. Despite her confinement, which would continue for most of her life, the young poet’s writing flourished. Her work was published, drawing the attention of two male mentors. One, like her father, encouraged her talent as well as submissive dependency on his guidance and approval.

More here.

How should we think of human rationality? The cognitive wherewithal to understand the world and bend it to our advantage is not a trophy of Western civilization; it’s the patrimony of our species. The San of the Kalahari Desert in southern Africa are one of the world’s oldest peoples, and their foraging lifestyle, maintained until recently, offers a glimpse of the ways in which humans spent most of their existence. Hunter-gatherers don’t just chuck spears at passing animals or help themselves to fruit and nuts growing around them. The tracking scientist Louis Liebenberg, who has worked with the San for decades, has described how they owe their survival to a scientific mindset. They reason their way from fragmentary data to remote conclusions with an intuitive grasp of logic, critical thinking, statistical reasoning, correlation and causation, and game theory.

How should we think of human rationality? The cognitive wherewithal to understand the world and bend it to our advantage is not a trophy of Western civilization; it’s the patrimony of our species. The San of the Kalahari Desert in southern Africa are one of the world’s oldest peoples, and their foraging lifestyle, maintained until recently, offers a glimpse of the ways in which humans spent most of their existence. Hunter-gatherers don’t just chuck spears at passing animals or help themselves to fruit and nuts growing around them. The tracking scientist Louis Liebenberg, who has worked with the San for decades, has described how they owe their survival to a scientific mindset. They reason their way from fragmentary data to remote conclusions with an intuitive grasp of logic, critical thinking, statistical reasoning, correlation and causation, and game theory. Servaas Storm over at INET:

Servaas Storm over at INET: Becca Rothfield in Boston Review:

Becca Rothfield in Boston Review: Adam Tooze at his podcast Ones and Tooze over at Foreign Policy:

Adam Tooze at his podcast Ones and Tooze over at Foreign Policy: Marco D’Eramo in NLR’s Sidecar (Photo by

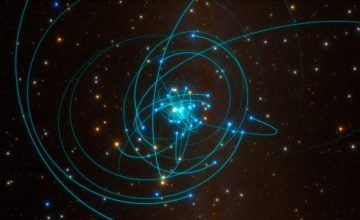

Marco D’Eramo in NLR’s Sidecar (Photo by  In December 1915, while serving on the Russian front, the German astronomer and mathematician Karl Schwarzschild sent a letter to Albert Einstein that contained the first precise solution to the equations of general relativity. Schwarzschild’s approach had been simple. He had plugged Einstein’s equations into a model that posited an ideal, perfectly spherical star, in order to calculate how its mass would warp the surrounding space. Schwarzschild’s solution was elegant, but it revealed something monstrous: If the same process were applied not to an ideal star but to one that had begun to collapse, its density and gravity would increase infinitely, creating an enclosed region of space-time, or a singularity, from which nothing could escape. Schwarzschild had given the world its first glimpse of black holes.

In December 1915, while serving on the Russian front, the German astronomer and mathematician Karl Schwarzschild sent a letter to Albert Einstein that contained the first precise solution to the equations of general relativity. Schwarzschild’s approach had been simple. He had plugged Einstein’s equations into a model that posited an ideal, perfectly spherical star, in order to calculate how its mass would warp the surrounding space. Schwarzschild’s solution was elegant, but it revealed something monstrous: If the same process were applied not to an ideal star but to one that had begun to collapse, its density and gravity would increase infinitely, creating an enclosed region of space-time, or a singularity, from which nothing could escape. Schwarzschild had given the world its first glimpse of black holes. The

The  Wole Soyinka the firebrand activist is always getting Wole Soyinka the writer into trouble.

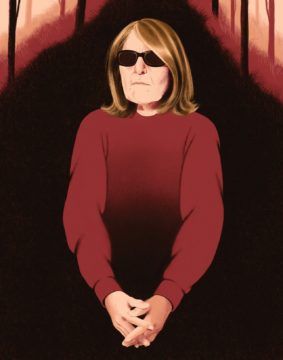

Wole Soyinka the firebrand activist is always getting Wole Soyinka the writer into trouble. You don’t encounter the fiction of Joy Williams without experiencing a measure of bewilderment. Williams, one of the country’s best living writers of the short story, draws praise from titans such as George Saunders, Don DeLillo, and Lauren Groff, and many of her readers, having imprinted on her wayward phrasing and screwball characters, will follow her anywhere. But the route can be disorienting, like climbing an uneven staircase in a dream. Her tales offer a dark, provisional illumination, and they make the kind of sense that disperses upon waking. For years, Williams has worn sunglasses at all hours, as if to blacken her vision. The central subject of art, she has written, is “nothingness.”

You don’t encounter the fiction of Joy Williams without experiencing a measure of bewilderment. Williams, one of the country’s best living writers of the short story, draws praise from titans such as George Saunders, Don DeLillo, and Lauren Groff, and many of her readers, having imprinted on her wayward phrasing and screwball characters, will follow her anywhere. But the route can be disorienting, like climbing an uneven staircase in a dream. Her tales offer a dark, provisional illumination, and they make the kind of sense that disperses upon waking. For years, Williams has worn sunglasses at all hours, as if to blacken her vision. The central subject of art, she has written, is “nothingness.”

If you want to predict the future accurately, you should be an incrementalist and accept that human nature doesn’t change along most axes. Meaning that the future will look a lot like the past. If Cicero were transported from ancient Rome to our time he would easily understand most things about our society. There’d be a short-term amazement at various new technologies and societal changes, but soon Cicero would settle in and be throwing out Trump/Sulla comparisons (or contradicting them), since many of the debates we face, like what to do about growing wealth inequality, or how to keep a democracy functional, are the same as in Roman times.

If you want to predict the future accurately, you should be an incrementalist and accept that human nature doesn’t change along most axes. Meaning that the future will look a lot like the past. If Cicero were transported from ancient Rome to our time he would easily understand most things about our society. There’d be a short-term amazement at various new technologies and societal changes, but soon Cicero would settle in and be throwing out Trump/Sulla comparisons (or contradicting them), since many of the debates we face, like what to do about growing wealth inequality, or how to keep a democracy functional, are the same as in Roman times. Barack Obama was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize during his first year in the White House, but he also became the first U.S. president to be at war during the entirety of his two terms in office. The irony of this contrast has often been noted. To historian and legal scholar Samuel Moyn, it represents more than a case of poor judgment by the Nobel committee—or, as others might see it, an example of how the toxic politics surrounding terrorism can blunt the best of intentions.

Barack Obama was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize during his first year in the White House, but he also became the first U.S. president to be at war during the entirety of his two terms in office. The irony of this contrast has often been noted. To historian and legal scholar Samuel Moyn, it represents more than a case of poor judgment by the Nobel committee—or, as others might see it, an example of how the toxic politics surrounding terrorism can blunt the best of intentions. I’M NOT ONE FOR FLATTERY and hyperbole, especially when reacting to exhibitions. There is already enough sycophancy to go around on social media—even in the feeds of those who should know better. I am therefore going against every fiber of my being when I say that the Cézanne drawing show at New York’s Museum of Modern Art is unequivocally a once-in-a-generation not-to-be-missed event.

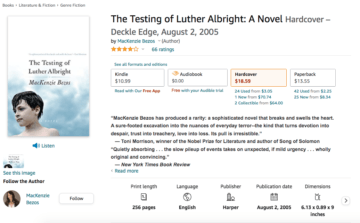

I’M NOT ONE FOR FLATTERY and hyperbole, especially when reacting to exhibitions. There is already enough sycophancy to go around on social media—even in the feeds of those who should know better. I am therefore going against every fiber of my being when I say that the Cézanne drawing show at New York’s Museum of Modern Art is unequivocally a once-in-a-generation not-to-be-missed event. The Testing of Luther Albright (2005) and Traps (2013) are perfectly good novels if one has a taste for it. The second thing that needs to be noted about them is that, after her divorce from Jeff Bezos, founder and controlling shareholder of Amazon, their author is the richest woman in the world, or close enough, worth in excess (as I write these words) of $60 billion, mostly from her holdings of Amazon stock. She is no doubt the wealthiest published novelist of all time by a factor of … whatever, a high number. Compared to her, J. K. Rowling is still poor.

The Testing of Luther Albright (2005) and Traps (2013) are perfectly good novels if one has a taste for it. The second thing that needs to be noted about them is that, after her divorce from Jeff Bezos, founder and controlling shareholder of Amazon, their author is the richest woman in the world, or close enough, worth in excess (as I write these words) of $60 billion, mostly from her holdings of Amazon stock. She is no doubt the wealthiest published novelist of all time by a factor of … whatever, a high number. Compared to her, J. K. Rowling is still poor.  ELIZABETH HOLMES SAYS

ELIZABETH HOLMES SAYS