Johanna Thomas-Corr in The Guardian:

At the beginning of Elena Ferrante’s last novel, The Lying Life of Adults (2020), the narrator recalls a moment of shame from early adolescence that left her feeling permanently untethered. “I slipped away, and am still slipping away, within these lines that are intended to give me a story,” she writes. Describing herself as “only a tangled knot”, she says: “Nobody, not even the one who at this moment is writing, knows if it contains the right thread for a story or is merely a snarled confusion of suffering, without redemption.”

At the beginning of Elena Ferrante’s last novel, The Lying Life of Adults (2020), the narrator recalls a moment of shame from early adolescence that left her feeling permanently untethered. “I slipped away, and am still slipping away, within these lines that are intended to give me a story,” she writes. Describing herself as “only a tangled knot”, she says: “Nobody, not even the one who at this moment is writing, knows if it contains the right thread for a story or is merely a snarled confusion of suffering, without redemption.”

The sense of self-estrangement, the ugly-beautiful imagery, the mood of anguish – these are the constants in Ferrante’s fiction, from her early first-person stories about desperate women whose lives are going to pieces to her Neapolitan Quartet that made Ferrante an international phenomenon – as well as the world’s most famous literary recluse. She has always been fascinated by the way reality is transformed into art. Who gets to tell whose story? What if the story I’m telling leads nowhere? Is fiction more truthful when seen behind a veil of lies?

More here.

When we experience shame, we feel bad; and when we inflict shame, we feel good. Those seem to be among the few points of consensus when it comes to what the historian Peter N. Stearns calls a “disputed emotion.” Unlike fear or anger, shame is “self-conscious”; it doesn’t erupt so much as coil around itself. It requires an awareness of others and their disapproval, and it has to be learned. Aristotle thought of it as fundamental to ethical behavior; Confucius saw it as essential to social order.

When we experience shame, we feel bad; and when we inflict shame, we feel good. Those seem to be among the few points of consensus when it comes to what the historian Peter N. Stearns calls a “disputed emotion.” Unlike fear or anger, shame is “self-conscious”; it doesn’t erupt so much as coil around itself. It requires an awareness of others and their disapproval, and it has to be learned. Aristotle thought of it as fundamental to ethical behavior; Confucius saw it as essential to social order. When did it become as hard to imagine what a good—or at least not as bad—internet might look like as to picture a world without the internet at all? Social-media mobs, conspiratorial thinking, deadly disinformation campaigns, gadget addiction, the funk of mass attention-deficit disorder: World-Wide-Web woes comprise a growth economy. The less acute but vague unease of our encounter with digital technology isn’t much alleviated by the possibility of imagining a truly off-the-grid alternative. (That a bit of shorthand like “off the grid” exists to describe a break from tech is as much a symptom of the problem as anything.) Perhaps to say that we feel backed into a corner by a claque of devices of our own making is not really to say much of anything at all.

When did it become as hard to imagine what a good—or at least not as bad—internet might look like as to picture a world without the internet at all? Social-media mobs, conspiratorial thinking, deadly disinformation campaigns, gadget addiction, the funk of mass attention-deficit disorder: World-Wide-Web woes comprise a growth economy. The less acute but vague unease of our encounter with digital technology isn’t much alleviated by the possibility of imagining a truly off-the-grid alternative. (That a bit of shorthand like “off the grid” exists to describe a break from tech is as much a symptom of the problem as anything.) Perhaps to say that we feel backed into a corner by a claque of devices of our own making is not really to say much of anything at all. Even after vaccination,

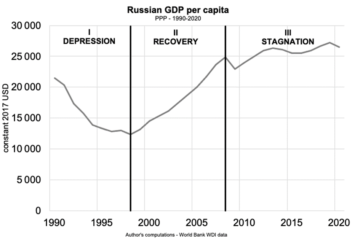

Even after vaccination,  The Russian invasion of Ukraine and ongoing responses by the global community have prompted renewed scrutiny of glaring energy and resource security gaps in the post-Cold War era. War, of course, is not new, nor is Russia’s aggression a unique threat to global energy security or decarbonization. However, as a nuclear-armed and energy export-intensive state engaged in an unprovoked attack on a neighboring country, Russia’s actions do pose novel challenges to national energy, security, and climate priorities.

The Russian invasion of Ukraine and ongoing responses by the global community have prompted renewed scrutiny of glaring energy and resource security gaps in the post-Cold War era. War, of course, is not new, nor is Russia’s aggression a unique threat to global energy security or decarbonization. However, as a nuclear-armed and energy export-intensive state engaged in an unprovoked attack on a neighboring country, Russia’s actions do pose novel challenges to national energy, security, and climate priorities.

Dominik A. Leusder in n+1:

Dominik A. Leusder in n+1: Cedric Durand in the New Left Review’s Sidecar:

Cedric Durand in the New Left Review’s Sidecar: Quinn Slobodian in Democracy:

Quinn Slobodian in Democracy: In her theory of writing, Ferrante stands opposed to someone like Joan Didion. Didion famously insisted that she wrote in order to find out what she thought. (“Had I been blessed with even limited access to my own mind there would have been no reason to write.”) In Ferrante’s case, the act is a flawed transcription of what she calls “the brain wave.” For Didion, everything was gained in the voyage from mind to pen; for Ferrante, much goes missing.

In her theory of writing, Ferrante stands opposed to someone like Joan Didion. Didion famously insisted that she wrote in order to find out what she thought. (“Had I been blessed with even limited access to my own mind there would have been no reason to write.”) In Ferrante’s case, the act is a flawed transcription of what she calls “the brain wave.” For Didion, everything was gained in the voyage from mind to pen; for Ferrante, much goes missing. Offering a wealth of examples ranging from cannibal spiders to sex-switching reef fish, Cooke dismantles a mass of misconceptions about binary sex roles, many of which can be traced back to that beloved bearded icon, Charles Darwin. According to Darwinian dogma, male animals fight one another for possession of females, “perform strange tactics” and mate promiscuously, propelled by a biological imperative to spread their abundant seed. Females are monogamous and passive; they wait patiently for their large, energy-rich eggs to be fertilised by cheap and tiny sperm, then selflessly give their all to their offspring.

Offering a wealth of examples ranging from cannibal spiders to sex-switching reef fish, Cooke dismantles a mass of misconceptions about binary sex roles, many of which can be traced back to that beloved bearded icon, Charles Darwin. According to Darwinian dogma, male animals fight one another for possession of females, “perform strange tactics” and mate promiscuously, propelled by a biological imperative to spread their abundant seed. Females are monogamous and passive; they wait patiently for their large, energy-rich eggs to be fertilised by cheap and tiny sperm, then selflessly give their all to their offspring. I find it difficult to imagine being a surgeon in the conditions in which my predecessors had to work — gloveless, covered in blood, with patients physically tied down and screaming in pain, not to mention a postoperative mortality of almost 50 percent. And yet in “Empire of the Scalpel,” Ira Rutkow quotes the 18th-century English surgeon William Cheselden, who wrote of himself: “No one ever endured more anxiety and sickness before an operation, yet from the time that I began to operate, all uneasiness ceased … [I was] never ruffled or disconcerted and [my hand] … never trembled during an operation.”

I find it difficult to imagine being a surgeon in the conditions in which my predecessors had to work — gloveless, covered in blood, with patients physically tied down and screaming in pain, not to mention a postoperative mortality of almost 50 percent. And yet in “Empire of the Scalpel,” Ira Rutkow quotes the 18th-century English surgeon William Cheselden, who wrote of himself: “No one ever endured more anxiety and sickness before an operation, yet from the time that I began to operate, all uneasiness ceased … [I was] never ruffled or disconcerted and [my hand] … never trembled during an operation.” The best moments on television shine for lots of different reasons. They can be heartwarming, tearjerking, shocking – or, sometimes, so viscerally uncomfortable that they keep replaying in your head long after the episode or even the series is over.

The best moments on television shine for lots of different reasons. They can be heartwarming, tearjerking, shocking – or, sometimes, so viscerally uncomfortable that they keep replaying in your head long after the episode or even the series is over. There is something that especially delights me about the story, and then also the paintings, of Vivian Suter, who happens to have a show up right now at the extension of the Reina Sofia Museum in Madrid, the extension being a large building in Retiro Park called the Velazquez Palace, which is packed full right now with hundreds of paintings by Vivian Suter, more paintings than I have maybe ever seen in a one-person show and this, indeed, is part of the delight of Vivian Suter, part of what is so fascinating about Vivian Suter, namely, that she doesn’t seem to care about her canvases all that much and so you can pack a smallish palace with hundreds of them, hanging all over the place, lying in piles, whatever, some of them covered in dirt and other detritus and a couple of them marked with what seems to be the footprints of dogs, pawprints I guess.

There is something that especially delights me about the story, and then also the paintings, of Vivian Suter, who happens to have a show up right now at the extension of the Reina Sofia Museum in Madrid, the extension being a large building in Retiro Park called the Velazquez Palace, which is packed full right now with hundreds of paintings by Vivian Suter, more paintings than I have maybe ever seen in a one-person show and this, indeed, is part of the delight of Vivian Suter, part of what is so fascinating about Vivian Suter, namely, that she doesn’t seem to care about her canvases all that much and so you can pack a smallish palace with hundreds of them, hanging all over the place, lying in piles, whatever, some of them covered in dirt and other detritus and a couple of them marked with what seems to be the footprints of dogs, pawprints I guess.