Julien Crockett in the Los Angeles Review of Books:

We hear about the loss of trust in our institutions and the need to reinvent them for the internet age. In short, we are living in a “crisis moment” — one ironically experienced by many of us while stuck at home.

Many have diagnosed these symptoms and proposed policy solutions, but few have done the hard work of rummaging around in the internet’s history to find the roots of the problems — and almost none have taken a truly long view. In The Internet Is Not What You Think It Is, Justin E. H. Smith, a philosopher and historian of science, argues that we’ve been much too narrow-minded in our understanding of the internet. In presenting a longue durée history, he challenges our assumptions about what the internet is and what we’re doing when we’re on it. Only by understanding the internet’s long history — by understanding the circumstances in which the internet’s many parts were conceived — can we, he claims, take back control of our lives and shape the internet in a way more conducive to human flourishing.

JULIEN CROCKETT: You credit the birth of The Internet Is Not What You Think It Is with a melancholic piece you wrote in 2018–’19, “It’s All Over.” Can you tell us about that piece and why it inspired you to write about the internet and ultimately this book?

JUSTIN E. H. SMITH: In the end, the book turned out to be something very different, both with respect to tone and argument from the 2018–’19 piece that I wrote as a “rant.” The book has some serious scholarly philosophical theses to defend, so it tones down the polemics. That said, “It’s All Over” inspired me to start trying to hone and articulate an argument about why the internet functions in society the way it does, and what the harms both seen and unseen about this function might be.

More here.

What often gets left out of chronicles about the Banda Islands, of which there are not many to begin with, are the perspectives of Bandanese survivors of the 1621 genocide, and their efforts to remember the past through stories and song. As Ghosh writes, ‘the modern gaze sees only one of the nutmeg’s two hemispheres… [it] is merely an inert object, a planet that contains no intrinsic meaning, and no properties other than those that make it a subject of science and commerce.’ THE NUTMEG’S CURSE shows us the hemisphere cast in a penumbra. Throughout the book, the chiaroscuro effect is extended to certain words as well, like ‘nature’, whose Western conception, Ghosh observes, ‘is the key element that simultaneously enables and conceals the true character of biopolitical warfare.’ The Bandanese have a very different relationship to nature, they view their islands as ‘places of dwelling that were enmeshed with human life in ways that were imaginative as well as material.’ Ghosh quotes the Indigenous thinker Max Liboiron, for whom land is ‘the unique entity that is the combined living spirit of plants, animals, water, humans, histories, and events.’ This is a ‘vitalist’ way of seeing the world that recognises the agency of material things. It’s also a view that any reader of Ghosh’s work implicitly senses. For those new to his writing, THE NUTMEG’S CURSE is not just a ‘parable for planetary crisis’, but also, albeit to a lesser extent, a kind of onboarding manual for his Ibis triple-decker.

What often gets left out of chronicles about the Banda Islands, of which there are not many to begin with, are the perspectives of Bandanese survivors of the 1621 genocide, and their efforts to remember the past through stories and song. As Ghosh writes, ‘the modern gaze sees only one of the nutmeg’s two hemispheres… [it] is merely an inert object, a planet that contains no intrinsic meaning, and no properties other than those that make it a subject of science and commerce.’ THE NUTMEG’S CURSE shows us the hemisphere cast in a penumbra. Throughout the book, the chiaroscuro effect is extended to certain words as well, like ‘nature’, whose Western conception, Ghosh observes, ‘is the key element that simultaneously enables and conceals the true character of biopolitical warfare.’ The Bandanese have a very different relationship to nature, they view their islands as ‘places of dwelling that were enmeshed with human life in ways that were imaginative as well as material.’ Ghosh quotes the Indigenous thinker Max Liboiron, for whom land is ‘the unique entity that is the combined living spirit of plants, animals, water, humans, histories, and events.’ This is a ‘vitalist’ way of seeing the world that recognises the agency of material things. It’s also a view that any reader of Ghosh’s work implicitly senses. For those new to his writing, THE NUTMEG’S CURSE is not just a ‘parable for planetary crisis’, but also, albeit to a lesser extent, a kind of onboarding manual for his Ibis triple-decker. Let me start by asking, Why a perfume? Why not several? A lot of people have perfume wardrobes. You can have a depersonalized relationship to perfume and just ask, How do I want to smell, in a performative way?

Let me start by asking, Why a perfume? Why not several? A lot of people have perfume wardrobes. You can have a depersonalized relationship to perfume and just ask, How do I want to smell, in a performative way? AS PRIVATE SPACE

AS PRIVATE SPACE  All pandemics end eventually. But how, exactly, will we know when the COVID-19 pandemic is really “over”? It turns out the answer to that question may lie more in sociology than epidemiology.

All pandemics end eventually. But how, exactly, will we know when the COVID-19 pandemic is really “over”? It turns out the answer to that question may lie more in sociology than epidemiology. On July 19, 1923, before

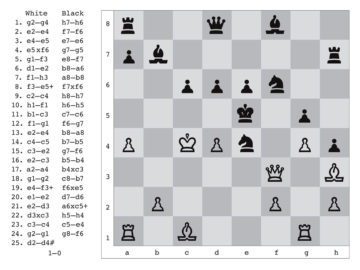

On July 19, 1923, before  Stimulated by Levi’s juxtaposition, and motivated by the possibilities of extending an Oulipian sensibility into the sphere of literary criticism (OuCriPo?), the authors set out to develop a means by which a given novel could express itself as a game of chess. Initial success here led to expanded ambition, since there was nothing to stop us from elaborating our modest analytic protocol into a full-fledged “engine” that would permit works of literature to confront one another on the chess board. We have advanced this project to what we think of as a workable tool for a certain sort of ludic literary investigation, and we present it here for the first time, together with some preliminary results drawn from several thousand games we have run to date. The current version of the program is playable on the Cabinet website [see end of article—Eds.], and we would be delighted if it proved useful to those wishing to pursue this or related lines of inquiry.

Stimulated by Levi’s juxtaposition, and motivated by the possibilities of extending an Oulipian sensibility into the sphere of literary criticism (OuCriPo?), the authors set out to develop a means by which a given novel could express itself as a game of chess. Initial success here led to expanded ambition, since there was nothing to stop us from elaborating our modest analytic protocol into a full-fledged “engine” that would permit works of literature to confront one another on the chess board. We have advanced this project to what we think of as a workable tool for a certain sort of ludic literary investigation, and we present it here for the first time, together with some preliminary results drawn from several thousand games we have run to date. The current version of the program is playable on the Cabinet website [see end of article—Eds.], and we would be delighted if it proved useful to those wishing to pursue this or related lines of inquiry. Ella Davis Hudson remembers stacking bricks to make a kitchen to play house. The next thing she knew, the 9 year old was running down the driveway, blood streaming from the gash above her eye.

Ella Davis Hudson remembers stacking bricks to make a kitchen to play house. The next thing she knew, the 9 year old was running down the driveway, blood streaming from the gash above her eye. The classic explanation of the gambler’s fallacy, proposed exactly fifty years ago by Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman, describes the fallacy as a cognitive bias resulting from the psychological makeup of human judgment. We will show that the gambler’s fallacy is not in fact a psychological phenomenon, but has its roots in the counter-intuitive mathematics of chance.

The classic explanation of the gambler’s fallacy, proposed exactly fifty years ago by Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman, describes the fallacy as a cognitive bias resulting from the psychological makeup of human judgment. We will show that the gambler’s fallacy is not in fact a psychological phenomenon, but has its roots in the counter-intuitive mathematics of chance. On August 20, 2020, the last day of the Democratic National Convention, Sister Simone Campbell, the executive director of NETWORK Lobby for Catholic Social Justice, delivered a

On August 20, 2020, the last day of the Democratic National Convention, Sister Simone Campbell, the executive director of NETWORK Lobby for Catholic Social Justice, delivered a  Dear Elena Ferrante, In your first essay/lecture you twice describe yourself as timid, but your work is extremely brave. I assume this is because the “I” that you describe as timid or lacking courage disappears and becomes many other “I”s as you write. You quote from a conversation between

Dear Elena Ferrante, In your first essay/lecture you twice describe yourself as timid, but your work is extremely brave. I assume this is because the “I” that you describe as timid or lacking courage disappears and becomes many other “I”s as you write. You quote from a conversation between  Almost one-third of more than 1,000 bodies taken to a morgue in Lusaka in 2020 and 2021 tested positive for SARS-CoV-2, implying that many more people died of COVID-19 in Zambia’s capital than official numbers suggest

Almost one-third of more than 1,000 bodies taken to a morgue in Lusaka in 2020 and 2021 tested positive for SARS-CoV-2, implying that many more people died of COVID-19 in Zambia’s capital than official numbers suggest What are the most authoritative quotation books? Two come immediately to mind: Bartlett’s Familiar Quotations (17th ed. 2002), to be released in an 18th edition later this year; and The Oxford Dictionary of Quotations (eighth ed. 2014).

What are the most authoritative quotation books? Two come immediately to mind: Bartlett’s Familiar Quotations (17th ed. 2002), to be released in an 18th edition later this year; and The Oxford Dictionary of Quotations (eighth ed. 2014). In the United States more than 90 percent of federal voting districts have been drawn in such a way that their election outcomes are more or less predetermined. Only

In the United States more than 90 percent of federal voting districts have been drawn in such a way that their election outcomes are more or less predetermined. Only