Afiya Zia in LSE:

The genealogy of blasphemy laws in Pakistan is not merely a story of legal prohibitions but of a shifting moral economy traversing colonial governance, post-colonial authoritarianism and contemporary populist religiosity. Introduced under British rule through Section 295 of the Indian Penal Code of 1860, these laws were designed to regulate communal sentiment and maintain order rather than serve as sacred doctrine. In post-colonial Pakistan, however, they have become sacralised.

The genealogy of blasphemy laws in Pakistan is not merely a story of legal prohibitions but of a shifting moral economy traversing colonial governance, post-colonial authoritarianism and contemporary populist religiosity. Introduced under British rule through Section 295 of the Indian Penal Code of 1860, these laws were designed to regulate communal sentiment and maintain order rather than serve as sacred doctrine. In post-colonial Pakistan, however, they have become sacralised.

General Zia-ul-Haq’s agenda of Islamisation, starting in 1979, transformed the colonial laws on blasphemy (known commonly as the ‘1927 Statutes’) into doctrinal absolutes, as ‘Hudud Ordinances’. Sections 295-B & 295-C criminalised defiling the Qur’an and insulting the Prophet, upgrading such acts into capital offences. What began as colonial order management mutated into a tool to empower clerics, suppress dissent and enforce Sunni orthodoxy.

Reliable data is scarce but the Centre for Social Justice (CSJ) records that between 1987–2024 at least 2,793 individuals were accused under blasphemy provisions, with 70–80 per cent of cases in Punjab province. In 2024 alone, 344 new cases were registered — the highest annual figure. CSJ also documented 104 extra-judicial killings between 1994–2024, demonstrating the lethal consequences of law and vigilante action. While minorities remain vulnerable, statistical trends now show that intra-Muslim accusations have surpassed those against non-Muslims and constitute the largest share of those accused of blasphemy.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Mount’s argument in this erudite, immensely entertaining book is that to be warm and witless (if by ‘witless’ one means devoid of irony, flippancy and cool) is not only to be on the side of the nice and good. It is also a form of power. Not that Mount isn’t witty – I have seldom read a work of cultural history that made me laugh out loud as frequently as this one did. But he is earnest in his belief that sentiment (called ‘sentimentality’ by those who disapprove of it) can prompt substantial social change, reverse injustices, ameliorate the lives of ill-treated people and – sentimentality alert! – enable love.

Mount’s argument in this erudite, immensely entertaining book is that to be warm and witless (if by ‘witless’ one means devoid of irony, flippancy and cool) is not only to be on the side of the nice and good. It is also a form of power. Not that Mount isn’t witty – I have seldom read a work of cultural history that made me laugh out loud as frequently as this one did. But he is earnest in his belief that sentiment (called ‘sentimentality’ by those who disapprove of it) can prompt substantial social change, reverse injustices, ameliorate the lives of ill-treated people and – sentimentality alert! – enable love.

He was a radical,

He was a radical, Guillermo del Toro has been shaping his vision for Victor Frankenstein’s monster since he was 11 years old, when Mary Shelley’s classic 1818 Gothic novel became his Bible, as he put it in a conversation in August.

Guillermo del Toro has been shaping his vision for Victor Frankenstein’s monster since he was 11 years old, when Mary Shelley’s classic 1818 Gothic novel became his Bible, as he put it in a conversation in August. Many of the molecules in our bodies are

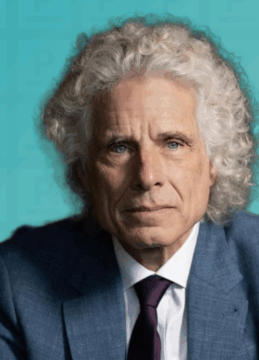

Many of the molecules in our bodies are  Steven Pinker: I’m using it in a technical sense, which is not the same as the everyday sense of conventional wisdom or something that people know. Common knowledge in the technical sense refers to a case where everyone knows that everyone knows something and everyone knows that and everyone knows it, ad infinitum. So I know something, you know it, I know that you know it, you know that I know it, I know that you know that I know it, et cetera.

Steven Pinker: I’m using it in a technical sense, which is not the same as the everyday sense of conventional wisdom or something that people know. Common knowledge in the technical sense refers to a case where everyone knows that everyone knows something and everyone knows that and everyone knows it, ad infinitum. So I know something, you know it, I know that you know it, you know that I know it, I know that you know that I know it, et cetera. Almost

Almost

At its core, The Ba***ds of Bollywood is a razor-sharp look at the dazzling yet treacherous world of

At its core, The Ba***ds of Bollywood is a razor-sharp look at the dazzling yet treacherous world of  The Ig Nobels were founded in 1991 by Marc Abrahams, editor of satirical magazine

The Ig Nobels were founded in 1991 by Marc Abrahams, editor of satirical magazine  As its September meeting approaches, the US Federal Reserve is once again coming under political pressure to lower rates. President Donald Trump has been calling for such a move for months – sometimes demanding cuts as large as

As its September meeting approaches, the US Federal Reserve is once again coming under political pressure to lower rates. President Donald Trump has been calling for such a move for months – sometimes demanding cuts as large as  My life’s mission has been to create safe, beneficial AI that will make the world a better place. But recently, I’ve been increasingly concerned about people starting to believe so strongly in AIs as conscious entities that they will advocate for “AI rights” and even citizenship. This development would represent a dangerous turn for the technology. It must be avoided. We must build AI for people, not to be people.

My life’s mission has been to create safe, beneficial AI that will make the world a better place. But recently, I’ve been increasingly concerned about people starting to believe so strongly in AIs as conscious entities that they will advocate for “AI rights” and even citizenship. This development would represent a dangerous turn for the technology. It must be avoided. We must build AI for people, not to be people.