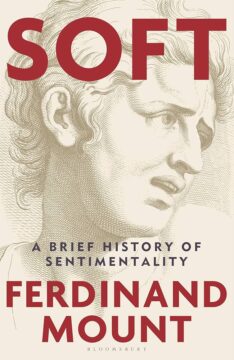

Lucy Hughes-Hallett at Literary Review:

Mount’s argument in this erudite, immensely entertaining book is that to be warm and witless (if by ‘witless’ one means devoid of irony, flippancy and cool) is not only to be on the side of the nice and good. It is also a form of power. Not that Mount isn’t witty – I have seldom read a work of cultural history that made me laugh out loud as frequently as this one did. But he is earnest in his belief that sentiment (called ‘sentimentality’ by those who disapprove of it) can prompt substantial social change, reverse injustices, ameliorate the lives of ill-treated people and – sentimentality alert! – enable love.

Mount’s argument in this erudite, immensely entertaining book is that to be warm and witless (if by ‘witless’ one means devoid of irony, flippancy and cool) is not only to be on the side of the nice and good. It is also a form of power. Not that Mount isn’t witty – I have seldom read a work of cultural history that made me laugh out loud as frequently as this one did. But he is earnest in his belief that sentiment (called ‘sentimentality’ by those who disapprove of it) can prompt substantial social change, reverse injustices, ameliorate the lives of ill-treated people and – sentimentality alert! – enable love.

He identifies three ‘sentimental revolutions’, each one followed by an era of chilly reaction. The first began with the troubadours. Mount accepts C S Lewis’s thesis that they invented courtly love, and he relates that development to the humanisation of medieval Christianity, with its motherly Virgin and crowds of kindly interceding saints. Then, after a ‘stony age’ of austere Protestantism and neoclassical Renaissance grandeur, came the age of sensibility. Mount sees the phenomenal success of Samuel Richardson’s novels as the manifestation of a cultural shift that led to the abolition of slavery and powered the social reforms advocated by Charles Dickens (scoffed at by Trollope as ‘Mr Popular Sentiment’).

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.