Steven French at Aeon Magazine:

This question forms the basis of what came to be known as the ‘measurement problem’. One influential answer emerged from the mind of one of the greatest mathematicians of all time, János (or ‘John’) von Neumann, who was responsible for many important advances, not only in pure mathematics and physics but also in computer design and game theory. He pointed out that when our spin detector interacts with the electron, the state of that combined system of the detector + electron will also be described by quantum theory as a superposition of possible states. And so will the state of the even larger combined system of the observer’s eye and brain + the detector + electron. However far we extend this chain, anything physical that interacts with the system will be described by the theory as a superposition of all the possible states that combined system could occupy, and so the crucial question above will remain unanswered. Hence, von Neumann concluded, it had to be something non-physical that somehow generates the transition from a superposition to the definite state as recorded on the device and noted by the observer – namely, the observer’s consciousness. (It is this argument that is the source of much of the so-called New Age commentary on quantum mechanics about how reality must somehow be observer-dependent, and so on.)

This question forms the basis of what came to be known as the ‘measurement problem’. One influential answer emerged from the mind of one of the greatest mathematicians of all time, János (or ‘John’) von Neumann, who was responsible for many important advances, not only in pure mathematics and physics but also in computer design and game theory. He pointed out that when our spin detector interacts with the electron, the state of that combined system of the detector + electron will also be described by quantum theory as a superposition of possible states. And so will the state of the even larger combined system of the observer’s eye and brain + the detector + electron. However far we extend this chain, anything physical that interacts with the system will be described by the theory as a superposition of all the possible states that combined system could occupy, and so the crucial question above will remain unanswered. Hence, von Neumann concluded, it had to be something non-physical that somehow generates the transition from a superposition to the definite state as recorded on the device and noted by the observer – namely, the observer’s consciousness. (It is this argument that is the source of much of the so-called New Age commentary on quantum mechanics about how reality must somehow be observer-dependent, and so on.)

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

S

S Gary Patti leaned in to study the rows of plastic tanks, where dozens of translucent zebrafish flickered through chemically treated water. Each tank contained a different substance — some notorious, others less well understood — all known or suspected carcinogens. Patti’s team is watching them closely, tracking which fish develop tumors, to try to find clues to one of the most unsettling medical puzzles of our time: Why are so many young people getting cancer?

Gary Patti leaned in to study the rows of plastic tanks, where dozens of translucent zebrafish flickered through chemically treated water. Each tank contained a different substance — some notorious, others less well understood — all known or suspected carcinogens. Patti’s team is watching them closely, tracking which fish develop tumors, to try to find clues to one of the most unsettling medical puzzles of our time: Why are so many young people getting cancer? T

T In 1994, a strange, pixelated machine came to life on a computer screen. It read a string of instructions, copied them, and built a clone of itself — just as the Hungarian-American Polymath John von Neumann had predicted half a century earlier. It was a striking demonstration of a profound idea: that life, at its core, might be computational.

In 1994, a strange, pixelated machine came to life on a computer screen. It read a string of instructions, copied them, and built a clone of itself — just as the Hungarian-American Polymath John von Neumann had predicted half a century earlier. It was a striking demonstration of a profound idea: that life, at its core, might be computational.

States and medical societies that long worked in concert with the CDC are breaking with federal recommendations, saying they no longer have faith in them amid the turmoil and Kennedy’s criticism of vaccines. Roughly seven months after Kennedy’s nomination was confirmed, they’re rushing to draft or release their own vaccine recommendations, while new groups are forming to issue immunization guidance and advice.

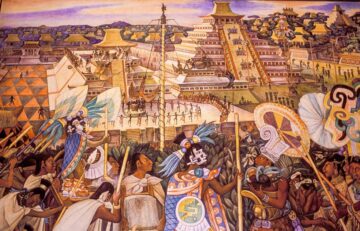

States and medical societies that long worked in concert with the CDC are breaking with federal recommendations, saying they no longer have faith in them amid the turmoil and Kennedy’s criticism of vaccines. Roughly seven months after Kennedy’s nomination was confirmed, they’re rushing to draft or release their own vaccine recommendations, while new groups are forming to issue immunization guidance and advice. When Spanish conquistador

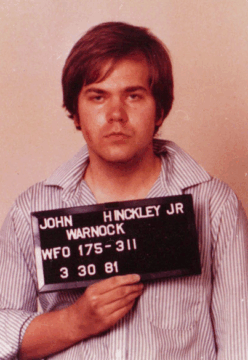

When Spanish conquistador  On the 30th of March, 1981, John Hinckley brought us into the world we all live in today. He did it by firing a .22 “Devastator” round into the chest of the president of the United States.

On the 30th of March, 1981, John Hinckley brought us into the world we all live in today. He did it by firing a .22 “Devastator” round into the chest of the president of the United States. By September 10th, Nepal had descended into a state of lawlessness, a country without a government or authority. The only national institution that survived—and that possessed the capability to restore order—was the Army, which, sheltering the civilian leadership, opened talks with representatives of the protest movement. Events then moved at dizzying speed. Within forty-eight hours, Nepal’s President had been forced to appoint an interim Prime Minister, dissolve the country’s elected Parliament, and announce new elections. As search teams set about recovering bodies from the charred government buildings, the death toll rose to more than seventy, and the number of injured exceeded two thousand.

By September 10th, Nepal had descended into a state of lawlessness, a country without a government or authority. The only national institution that survived—and that possessed the capability to restore order—was the Army, which, sheltering the civilian leadership, opened talks with representatives of the protest movement. Events then moved at dizzying speed. Within forty-eight hours, Nepal’s President had been forced to appoint an interim Prime Minister, dissolve the country’s elected Parliament, and announce new elections. As search teams set about recovering bodies from the charred government buildings, the death toll rose to more than seventy, and the number of injured exceeded two thousand.

Human history is rife with contentions about the purity (and superiority) of the bloodlines of one group over another and claims over ancestral homelands.

Human history is rife with contentions about the purity (and superiority) of the bloodlines of one group over another and claims over ancestral homelands.

Cancer is one of the most common causes of death in people, and case numbers are rising. At current rates, about one in two Australians can expect a cancer diagnosis by the age of 85. Vets, livestock farmers, pet owners and anyone who spends time around animals will also know that cancer can strike a whole range of creatures. But did you know it’s not just a disease in the animal kingdom?

Cancer is one of the most common causes of death in people, and case numbers are rising. At current rates, about one in two Australians can expect a cancer diagnosis by the age of 85. Vets, livestock farmers, pet owners and anyone who spends time around animals will also know that cancer can strike a whole range of creatures. But did you know it’s not just a disease in the animal kingdom? The first door was in Tokyo, in the Roppongi district. He said he discovered it in a state of boredom, or more exactly, in that mental state that walking in Tokyo is particularly inclined to produce—a state of visual overstimulation that is like boredom, but also strangely close to a kind of hypersensitivity, a readiness to see a hidden order suddenly emerge in the dense life of the city. The door that captured his attention had been placed across a blind alleyway. It had no special features, but was remarkable for being unmarked, without a name, bell, or knocker. Oddly, the cracked cinderblocks that framed the door on either side seemed older than the buildings that they abutted. Behind the door were the branches of some trees, giving the entire scene the hint of a hortus conclusus, a walled garden in a neighborhood that was not known for being green. An electrical conduit snaked along the pavement and over the wall.

The first door was in Tokyo, in the Roppongi district. He said he discovered it in a state of boredom, or more exactly, in that mental state that walking in Tokyo is particularly inclined to produce—a state of visual overstimulation that is like boredom, but also strangely close to a kind of hypersensitivity, a readiness to see a hidden order suddenly emerge in the dense life of the city. The door that captured his attention had been placed across a blind alleyway. It had no special features, but was remarkable for being unmarked, without a name, bell, or knocker. Oddly, the cracked cinderblocks that framed the door on either side seemed older than the buildings that they abutted. Behind the door were the branches of some trees, giving the entire scene the hint of a hortus conclusus, a walled garden in a neighborhood that was not known for being green. An electrical conduit snaked along the pavement and over the wall.