Category: Recommended Reading

What’s going on with Georgia’s Trump investigation?

Ben Jacobs in Vox:

The House January 6 committee isn’t the only entity investigating former President Donald Trump and his efforts to overturn the 2020 presidential election. On Tuesday, a special grand jury in Fulton County, Georgia, subpoenaed members of Trump’s inner circle, including Sen. Lindsey Graham (R-SC) and Rudy Giuliani. While the January 6 committee has been holding hearings on national television, the grand jury has been doing its work behind closed doors since early this year. Vox spoke to Tamar Hallerman, the ace reporter for the Atlanta Journal-Constitution covering the special grand jury who first reported news of the subpoenas, to understand what was happening and how this differs from the congressional committee. The interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

The House January 6 committee isn’t the only entity investigating former President Donald Trump and his efforts to overturn the 2020 presidential election. On Tuesday, a special grand jury in Fulton County, Georgia, subpoenaed members of Trump’s inner circle, including Sen. Lindsey Graham (R-SC) and Rudy Giuliani. While the January 6 committee has been holding hearings on national television, the grand jury has been doing its work behind closed doors since early this year. Vox spoke to Tamar Hallerman, the ace reporter for the Atlanta Journal-Constitution covering the special grand jury who first reported news of the subpoenas, to understand what was happening and how this differs from the congressional committee. The interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Ben Jacobs

What is this special grand jury doing?

This is an investigative grand jury, which is slightly different from a regular grand jury that would hear every felony under the sun. It is focused on this one exclusive case. The whole idea is that they really can become experts and do a deep dive on everything to overturn Georgia’s election results. The order from the judge establishing the grand jury came in January, I don’t think it even mentions Trump’s name, but he’s central to all of this. Based on the witnesses that have come in, prosecutor Fani Willis is casting a really wide net. She’s brought in a parade of witnesses between June 2 and now, which has stretched all the way from local elections officials to a publicist for Kanye West and R. Kelly, and now into the inner circle of Donald Trump.

More here.

The Rise of Dissociation Music

Jayson Greene at Pitchfork:

Everyone is “dissociating.” Over the past few years, it’s become an open-source cultural term, ripe for applying (or misapplying) to all kinds of circumstances where people feel the need to turn off and tune out. One woman I know is currently dissociating via a series of increasingly eccentric hobbies—bead necklaces, candle making, metal-detecting. She’s hardly alone. The go-to pose on Instagram right now is the “dissociative pout,” where you assume the blankest expression you can muster. The cultural critic Rayne Fisher-Quann, who coined the term, also gave a name to the larger aesthetic—“lobotomy-chic”—and trawling TikTok or Twitter you can find countless riffs on the idea, from fake Claire’s ads advertising “self-care” lobotomies to Doomer memes about the hopelessness of escaping late capitalism. Lack of affect is the new affect.

Everyone is “dissociating.” Over the past few years, it’s become an open-source cultural term, ripe for applying (or misapplying) to all kinds of circumstances where people feel the need to turn off and tune out. One woman I know is currently dissociating via a series of increasingly eccentric hobbies—bead necklaces, candle making, metal-detecting. She’s hardly alone. The go-to pose on Instagram right now is the “dissociative pout,” where you assume the blankest expression you can muster. The cultural critic Rayne Fisher-Quann, who coined the term, also gave a name to the larger aesthetic—“lobotomy-chic”—and trawling TikTok or Twitter you can find countless riffs on the idea, from fake Claire’s ads advertising “self-care” lobotomies to Doomer memes about the hopelessness of escaping late capitalism. Lack of affect is the new affect.

So what’s happening? The easy answer is: everything.

more here.

Dream-Child: A Life of Charles Lamb

Edward Weech at Literary Review:

Despite being among the most entertaining and accessible of Romantic authors, Charles Lamb (1775–1834) has been out of fashion for many years. After his death, generations of Victorians and Edwardians continued to be charmed by his essays, letters and children’s books. But he exerted less lasting influence than more philosophical peers, such as Samuel Taylor Coleridge and William Wordsworth, and in the interwar period, changing tastes and Leavisite critical hostility contributed to Lamb being dropped from the popular Romantic canon. Lamb has always attracted admirers (notably in the ranks of the Charles Lamb Society) and numerous books on aspects of his life and work have been published. Yet, as Eric G Wilson observes, Dream-Child is the first full-scale biography in over a century.

Despite being among the most entertaining and accessible of Romantic authors, Charles Lamb (1775–1834) has been out of fashion for many years. After his death, generations of Victorians and Edwardians continued to be charmed by his essays, letters and children’s books. But he exerted less lasting influence than more philosophical peers, such as Samuel Taylor Coleridge and William Wordsworth, and in the interwar period, changing tastes and Leavisite critical hostility contributed to Lamb being dropped from the popular Romantic canon. Lamb has always attracted admirers (notably in the ranks of the Charles Lamb Society) and numerous books on aspects of his life and work have been published. Yet, as Eric G Wilson observes, Dream-Child is the first full-scale biography in over a century.

Covering the gamut of Lamb’s life and literary career, Wilson aims to demonstrate that Lamb ‘speaks to our age’, highlighting his enthusiasm for ‘the grit and speed and diversity of the urban’ and his ‘fluid, collaborative vision of identity’.

more here.

What Should We Maximise? Peter Singer on Utilitarianism

Thursday, July 7, 2022

Does George Saunders’s “Escape From Spiderhead” Stand Up on Film?

Jonathan Russell Clark in Literary Hub:

George Saunders is legendary in the literary community. He’s one of the few authors who has made a name for himself almost entirely on short stories, a feat all the more impressive considering how unmarketable story collections are. He now teaches at a highly respected MFA program at Syracuse, but in the bio of his first book, CivilWarLand in Bad Decline (1996), it says that he “works as a geophysical engineer” and that “he has explored for oil in Sumatra, played guitar in a Texas bar band, and worked in a slaughterhouse.” He was 38. In the 26 years since his debut, Saunders has won MacArthur and Guggenheim fellowships, the Story Prize, the Folio Prize, the Booker Prize, a World Fantasy Award, and four National Magazine Awards.

George Saunders is legendary in the literary community. He’s one of the few authors who has made a name for himself almost entirely on short stories, a feat all the more impressive considering how unmarketable story collections are. He now teaches at a highly respected MFA program at Syracuse, but in the bio of his first book, CivilWarLand in Bad Decline (1996), it says that he “works as a geophysical engineer” and that “he has explored for oil in Sumatra, played guitar in a Texas bar band, and worked in a slaughterhouse.” He was 38. In the 26 years since his debut, Saunders has won MacArthur and Guggenheim fellowships, the Story Prize, the Folio Prize, the Booker Prize, a World Fantasy Award, and four National Magazine Awards.

Outside the literary world, however, Saunders isn’t exactly what you’d call a household name. Besides the fact that he primarily operates in the short-story form and that his only novel is, like his stories, an odd, experimental work about Abraham Lincoln hanging out in purgatory while grieving the death of his son, Saunders’s whole thing is dark and strange and satirical and, most significantly, morally aware tales. Some of them are just weird as hell, and all of them are thematically or ethically complex. His writing isn’t the stuff of mass popularity.

More here.

One Day, AI Will Seem as Human as Anyone. What Then?

Joanna J. Bryson in Wired:

For many last week, their engagement with Google’s LaMDA—and its alleged sentience—was broken by an Economist article by AI legend Douglas Hofstadter in which he and his friend David Bender show how “mind-bogglingly hollow” the same technology sounds when asked a nonsense question like “How many pieces of sound are there in a typical cumulonimbus cloud?”

For many last week, their engagement with Google’s LaMDA—and its alleged sentience—was broken by an Economist article by AI legend Douglas Hofstadter in which he and his friend David Bender show how “mind-bogglingly hollow” the same technology sounds when asked a nonsense question like “How many pieces of sound are there in a typical cumulonimbus cloud?”

But I doubt we’ll have these obvious tells of inhumanity forever.

From here on out, the safe use of artificial intelligence requires demystifying the human condition. If we can’t recognize and understand how AI works—if even expert engineers can fool themselves into detecting agency in a “stochastic parrot”—then we have no means of protecting ourselves from negligent or malevolent products.

More here.

Inside Ukraine’s lobbying blitz in Washington

Jonathan Guyer at Vox:

Ukraine has unleashed an incredible influence campaign in Washington. There’s a lag to the filing of lobbying disclosures. But even in the lead-up to the war last year, Ukraine’s lobbyists made more than 10,000 contacts with Congress, think tanks, and journalists. That’s higher than the well-funded lobbyists of Saudi Arabia, and experts on foreign lobbying told Vox they expect that this year’s number will grow much higher.

Ukraine has unleashed an incredible influence campaign in Washington. There’s a lag to the filing of lobbying disclosures. But even in the lead-up to the war last year, Ukraine’s lobbyists made more than 10,000 contacts with Congress, think tanks, and journalists. That’s higher than the well-funded lobbyists of Saudi Arabia, and experts on foreign lobbying told Vox they expect that this year’s number will grow much higher.

This spring, I’ve been invited to an elegant dinner with a parliamentary delegation and morning briefings (no breakfast, just coffee) at think tanks with Ukraine’s chief negotiator with Russia. Foreign policy reporters in DC have been inundated with requests. A journalist from another outlet, who asked for anonymity to be blunt, concurred: It’s been “a nonstop cycle” of Ukrainian visitors in Washington, they told me, “And think tanks that have basically become lobbyists but with a nonprofit status.”

More here.

Naples Will Never Escape The Shadow Of Vesuvius

Ian Thomson at The Spectator:

Naples, the tatterdemalion capital of the Italian south, is said to be awash with heroin. Chinese-run morphine refineries on its outskirts masquerade as ‘legitimate’ couture operations that transform bolts of Chinese silk into contraband Dolce & Gabbana or Versace. The textile sweatshops are controlled by the Neapolitan mafia, or Camorra. All this was exposed by the Italian journalist Roberto Saviano in his scorching reportage, Gomorrah. Published in Italy in 2006, Saviano’s was nevertheless a partial account, in which the carnival city of mandolins and ‘O Sole Mio’ was overrun by Armani-coutured killer-capitalists.

Naples, the tatterdemalion capital of the Italian south, is said to be awash with heroin. Chinese-run morphine refineries on its outskirts masquerade as ‘legitimate’ couture operations that transform bolts of Chinese silk into contraband Dolce & Gabbana or Versace. The textile sweatshops are controlled by the Neapolitan mafia, or Camorra. All this was exposed by the Italian journalist Roberto Saviano in his scorching reportage, Gomorrah. Published in Italy in 2006, Saviano’s was nevertheless a partial account, in which the carnival city of mandolins and ‘O Sole Mio’ was overrun by Armani-coutured killer-capitalists.

Marius Kociejowski, poet, essayist and travel writer, is alert to the city’s reputation for Camorra and pickpocketing crime. ‘There is no getting around the fact that Naples is a bit of a shambles,’ he writes.

more here.

Great Art Explained: The Milkmaid by Johannes Vermeer

The Literary Afterlife of F.O. Matthiessen

Scott Bane at The Millions:

American Renaissance: Art and Expression in the Age of Emerson and Whitman remains Matthiessen’s best-known work. Published in 1941, it surveys the writing of Emerson, Thoreau, Hawthorne, Melville, and Whitman, who published many of their seminal works in the window of 1850 to 1855, in the run-up to the Civil War. The book contributed to the birth of American Studies and secured Matthiessen’s reputation as one of the leading critics of his day. But since the peak of Matthiessen’s popularity in the early-to-mid 20th century, literary scholarship and studies has largely moved on. Matthiessen’s understanding of canonical literature skewed white and male, whereas most critics and writers today debate the relevancy of a canon in the first place, much less who gets into it. Despite some of its outdated views, the book undeniably helped shape a new discipline—a rare feat, especially in the humanities—so Matthiessen has remained a force to contend with in scholarly debate, even if only to react against his ideas and literary judgments.

American Renaissance: Art and Expression in the Age of Emerson and Whitman remains Matthiessen’s best-known work. Published in 1941, it surveys the writing of Emerson, Thoreau, Hawthorne, Melville, and Whitman, who published many of their seminal works in the window of 1850 to 1855, in the run-up to the Civil War. The book contributed to the birth of American Studies and secured Matthiessen’s reputation as one of the leading critics of his day. But since the peak of Matthiessen’s popularity in the early-to-mid 20th century, literary scholarship and studies has largely moved on. Matthiessen’s understanding of canonical literature skewed white and male, whereas most critics and writers today debate the relevancy of a canon in the first place, much less who gets into it. Despite some of its outdated views, the book undeniably helped shape a new discipline—a rare feat, especially in the humanities—so Matthiessen has remained a force to contend with in scholarly debate, even if only to react against his ideas and literary judgments.

Despite Matthiessen’s wealthy family and his privileged path to the ivory tower of academia, he was an ardent socialist activist and champion of economic equality.

more here.

Patti Smith | Broken Record

Thursday Poem

No One Looked Back

As if the 360 days of sunshine would never end.

As if the balance of rain to earth would remain even

As if valleys and terraced hills would provide vineyards and fruit

……….. forever

As if the earth, light, water and wind worked

………. in concert, in harmony, had consulted with each other.

No one expected a raging wind to rip the trees from their roots

………. Or an ocean to roil through cities once so erect

………. Or a sun to crack and parch and not feed and nurture

………. Or a prophetic dream that would come to be

………. Or a darkness that would color every season

by Maria Lisella

from The Rutherford Red Wheelbarrow #3, 2010

How insect ‘civilisations’ recast our place in the Universe

Thomas Moynihan in BBC:

It is 1919, and a young astronomer turns a street corner in Pasadena, California. Something seemingly humdrum on the ground distracts him. It’s an ant heap. Dropping to his knees, peering closer, he has an epiphany – about deep time, our place within it, and humanity’s uncertain fate.

It is 1919, and a young astronomer turns a street corner in Pasadena, California. Something seemingly humdrum on the ground distracts him. It’s an ant heap. Dropping to his knees, peering closer, he has an epiphany – about deep time, our place within it, and humanity’s uncertain fate.

The astronomer was Harlow Shapley. He worked nearby at Mount Wilson Observatory: peering into space. With help from colleagues like Henrietta Leavitt, Annie Jump Cannon, and Cecilia Payne-Gaposchkin, Shapley went on to “measure” the Milky Way. Their work revealed that we don’t live at our galaxy’s centre, and that there are many other galaxies besides.

A lifelong advocate of progressive causes, Shapley also reflected regularly upon humanity’s long-term future, alongside the risks jeopardising it. He was among the first to suggest, during a lecture given while World War Two raged, that humanity should learn the lesson from 1918’s pandemic and prepare properly for the next one. Instead of battling each other, he prescribed a “design for fighting” the risks facing all of humanity: declaring war on the gamut of evils, from pandemics to poverty, endangering the whole globe. (Only two audience members applauded; it appears we didn’t take heed.)

More here.

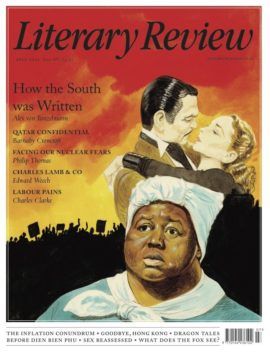

The Wrath to Come: Gone with the Wind and the Lies America Tells

Sarah Churchwell in Literary Review:

The night before Gone with the Wind’s Atlanta premiere in 1939, there was a ball at a plantation. Dressed as slaves, the children of the black Ebenezer Baptist Church choir performed for an all-white audience. They sang ‘There’s Plenty of Good Room in Heaven’; the actress playing Belle Watling, Rhett Butler’s tart with a heart, wept. The scene is already striking: a painfully literal example of the mythologising of the South for white consumption, redefining slavery as harmless and the slaves themselves as grateful. Yet Sarah Churchwell finds a jaw-dropping detail: ‘One of the little Black children dressed as a slave and bringing a sentimental tear to white America’s eye was a ten-year-old boy named Martin Luther King, Jr, who would be dead in thirty years for daring to dream of racial equality in America.’

The night before Gone with the Wind’s Atlanta premiere in 1939, there was a ball at a plantation. Dressed as slaves, the children of the black Ebenezer Baptist Church choir performed for an all-white audience. They sang ‘There’s Plenty of Good Room in Heaven’; the actress playing Belle Watling, Rhett Butler’s tart with a heart, wept. The scene is already striking: a painfully literal example of the mythologising of the South for white consumption, redefining slavery as harmless and the slaves themselves as grateful. Yet Sarah Churchwell finds a jaw-dropping detail: ‘One of the little Black children dressed as a slave and bringing a sentimental tear to white America’s eye was a ten-year-old boy named Martin Luther King, Jr, who would be dead in thirty years for daring to dream of racial equality in America.’

Churchwell has written about American mythology before, notably in Behold America: A History of America First and the American Dream, as well as in works on Marilyn Monroe and The Great Gatsby. This time it feels like she has hit the motherlode: ‘The heart of the [American] myth, as well as its mind and its nervous system, most of its arguments and beliefs, its loves and hates, its lies and confusions and defence mechanisms and wish fulfilments, are all captured (for the most part inadvertently) in America’s most famous epic romance.’ For Churchwell, ‘Gone with the Wind provides a kind of skeleton key, unlocking America’s illusions about itself.’

More here.

Wednesday, July 6, 2022

Nixon and Watergate ‑ An American Tragedy

Kevin Stevens at the Dublin Review of Books:

Why, from the get-go, did Nixon do the very thing that could bring him down? Why didn’t he condemn the burglary, claim he knew nothing about it (which was factually true), and fire those responsible? He had the nation on his side. He had worked well with Congress. He was odds-on favourite to win a second term. With Henry Kissinger, he had set a foreign policy agenda of unprecedented ambition: that February, he’d been the first US president to visit the People’s Republic of China and in May he was the first president to set foot in Moscow. Vietnam notwithstanding, he had created a legacy of international success that he believed would make him one of history’s great peacemakers. He had much to lose.

Why, from the get-go, did Nixon do the very thing that could bring him down? Why didn’t he condemn the burglary, claim he knew nothing about it (which was factually true), and fire those responsible? He had the nation on his side. He had worked well with Congress. He was odds-on favourite to win a second term. With Henry Kissinger, he had set a foreign policy agenda of unprecedented ambition: that February, he’d been the first US president to visit the People’s Republic of China and in May he was the first president to set foot in Moscow. Vietnam notwithstanding, he had created a legacy of international success that he believed would make him one of history’s great peacemakers. He had much to lose.

Yet as two new books on Watergate make clear, the cover-up was inevitable. The break-in was not a one-off but simply the latest in a string of illegal activities that Nixon’s team had sanctioned, planned, funded and kept secret, all at the behest of the president. The DNC burglary had to be kept dark because any light shed on its genesis would illuminate four years of dirty tricks.

more here.

The Nixon-Frost Interview

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VF_mQwJ7wd4&ab_channel=ReneGonzalez

The Last Days of Roger Federer

Asad Raza interviews Geoff Dyer at Bookforum:

ASAD RAZA: Your new book, The Last Days of Roger Federer (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, $28), is in part a meditation on the tennis great and his retirement. It’s also about the late careers of other athletes, writers, artists, and musicians—Bob Dylan, Eve Babitz, Beethoven, to name a few. In this sense, you are writing about time, and this is reflected in the book’s unique formal structure. Can you tell me how that came about?

ASAD RAZA: Your new book, The Last Days of Roger Federer (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, $28), is in part a meditation on the tennis great and his retirement. It’s also about the late careers of other athletes, writers, artists, and musicians—Bob Dylan, Eve Babitz, Beethoven, to name a few. In this sense, you are writing about time, and this is reflected in the book’s unique formal structure. Can you tell me how that came about?

GEOFF DYER: With great pleasure! The book isn’t one of these essay hampers, which I’ve published, where you sort of dump into a big bucket the stuff you’ve written for the last ten years or whatever. It’s actually got a very intricate structure. With Nietzsche occupying a dominant place in the book, I felt it would be nice if it could reflect his idea of the eternal recurrence in some way, so I started thinking of loops, which were in my mind anyway because there’s also a section about William Basinski’s Disintegration Loops. I liked the idea of the number sixty, which tends to suggest either sixty seconds or sixty minutes, going round like that. So the book has three parts, or loops, made up of sixty sections. In the discussion of the eternal recurrence, I mention Christian Marclay’s twenty-four-hour film, The Clock. There’s no climactic moment on the hour, you just keep looping round for 86,400 seconds. The book, at a certain point, was about 90,000 words, so I thought that, with all sorts of adding and subtracting, I’d make the number of words the same as the number of seconds in the day—though I only reveal this right at the end, in the postscript.

more here.

Agatha Christie’s “At Bertram’s Hotel”

Briallen Hopper at Public Books:

Unlike Agatha Christie’s best known novels, At Bertram’s Hotel (1965) barely has a plot. Its one murder takes place almost three-quarters of the way through the book, and it is solved more through intuition than detection. Though Miss Marple is present, she has little to do beyond eating muffins and shopping for tea towels—or, as she calls them, “glass cloths.”

Unlike Agatha Christie’s best known novels, At Bertram’s Hotel (1965) barely has a plot. Its one murder takes place almost three-quarters of the way through the book, and it is solved more through intuition than detection. Though Miss Marple is present, she has little to do beyond eating muffins and shopping for tea towels—or, as she calls them, “glass cloths.”

But I have been rereading Agatha Christie for decades, and I have a special admiration for At Bertram’s Hotel. Christie’s more streamlined Art Deco style of the 1920s and ’30s yields here to the expansive nonchalance of a late-career writer whose sales figures were on track to rival those of Shakespeare and God. What makes it unsatisfying as a work of detection paradoxically makes it excellent as a case study of why one might read mystery novels—and, more to the point, why one might reread them.

More here.

Vaclav Smil: Time to Get Real on Climate Change

Vaclav Smil at Yale Environment 360:

Clearly, to conclude that we will be able to achieve decarbonization anytime soon, effectively, and on the required scale runs against all past evidence.

Clearly, to conclude that we will be able to achieve decarbonization anytime soon, effectively, and on the required scale runs against all past evidence.

The problem is that rather than take a clear-eyed look at the enormous challenges of phasing out the fossil fuels that are the basis of modern industrial economies, we have ricocheted between catastrophism on one hand and the magical thinking of “techno-optimism” on the other.

In recent decades we have multiplied our reliance on the combustion of fossil fuels, resulting in a dependence that will not be severed easily, or inexpensively. How rapidly we can change this remains unclear. Add to this all other environmental worries, and you must conclude that the key existential question — can humanity realize its aspirations within the safe boundaries of our biosphere? — has no easy answers. But it is imperative that we understand the facts of the matter. Only then can we tackle the problem effectively.

More here.