Branko Milanovic over at his substack Global Inequality and More 3.0:

Branko Milanovic over at his substack Global Inequality and More 3.0:

That today’s world situation is the worst since the end of the Second World War is not an excessive, nor original, statement. As we teeter on the brink of a nuclear war, it does not require too many words to convince people that this is so.

The question is: how did we get here? And is there a way out?

To understand how we got here, we need to go to the end of the Cold War. That war, like the World War I, ended with the two sides understanding the end differently: the West understood the end of the Cold War as its comprehensive victory over Russia; Russia understood it as the end of the ideological competition between capitalism and communism: Russia jettisoned communism, and hence it was to be just another power alongside other capitalist powers.

The origin of today’s conflict lies in that misunderstanding. Many books have already been written about it, and more will be. But this is not all. The Euro-American world took a bad turn in the 1990s because both the (former) West and the (former) East took a bad turn. The West rejected social-democracy with its conciliatory attitude domestically and willingness to envisage a world without adversarial military blocs internationally for neoliberalism at home and militant expansion abroad. The (former) East embraced privatization and deregulation in economics, and an exclusivist nationalism in the national ideologies underlying the newly-independent states.

These extreme ideologies, East and West, were the very opposite of what people of goodwill hoped for.

More here.

Terry Eagleton in Sidecar [h/t: Leonard Benardo]:

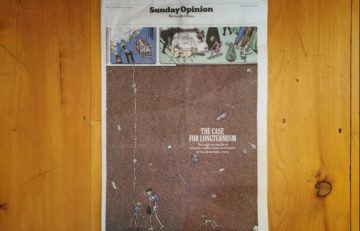

Terry Eagleton in Sidecar [h/t: Leonard Benardo]: Gregg studies animal behavior and is an expert in dolphin communication. He shows how human cognition is extraordinarily complex, allowing us to paint pictures and write symphonies. We can share ideas with one another so that we don’t have to rely only on gut instinct or direct experience in order to learn. But this compulsion to learn can be superfluous, he says. We accumulate what the philosopher Ruth Garrett Millikan calls “dead facts” — knowledge about the world that is useless for daily living, like the distance to the moon, or what happened in the latest episode of “Succession.” Our collections of dead facts, Gregg writes, “help us to imagine an infinite number of solutions to whatever problems we encounter — for good or ill.”

Gregg studies animal behavior and is an expert in dolphin communication. He shows how human cognition is extraordinarily complex, allowing us to paint pictures and write symphonies. We can share ideas with one another so that we don’t have to rely only on gut instinct or direct experience in order to learn. But this compulsion to learn can be superfluous, he says. We accumulate what the philosopher Ruth Garrett Millikan calls “dead facts” — knowledge about the world that is useless for daily living, like the distance to the moon, or what happened in the latest episode of “Succession.” Our collections of dead facts, Gregg writes, “help us to imagine an infinite number of solutions to whatever problems we encounter — for good or ill.” The more we learn about the FBI’s search of Mar-a-Lago, the sillier — and more sinister — the overcaffeinated Republican defenses of former president Donald Trump look. A genius-level spinmeister, Trump set the tone with a

The more we learn about the FBI’s search of Mar-a-Lago, the sillier — and more sinister — the overcaffeinated Republican defenses of former president Donald Trump look. A genius-level spinmeister, Trump set the tone with a  R

R The most famous TV ad in the Orwellian year of 1984, carefully themed to the novel named for this year, was for the

The most famous TV ad in the Orwellian year of 1984, carefully themed to the novel named for this year, was for the  For most of us,

For most of us,  Effective altruism—EA for short—is a pretty straightforward extension of utilitarian moral philosophy and drew much of its founding inspiration from the most famous living utilitarian philosopher, Peter Singer. The basic idea is that you should maximize the amount of increased human welfare per dollar of philanthropic donation or per hour of charitable work. A classic EA expenditure is on mosquito nets: You can actually count the lives you’re theoretically saving from the ravages of malaria and compare that with the number of lives you could have saved by, say, funding a water purification project.

Effective altruism—EA for short—is a pretty straightforward extension of utilitarian moral philosophy and drew much of its founding inspiration from the most famous living utilitarian philosopher, Peter Singer. The basic idea is that you should maximize the amount of increased human welfare per dollar of philanthropic donation or per hour of charitable work. A classic EA expenditure is on mosquito nets: You can actually count the lives you’re theoretically saving from the ravages of malaria and compare that with the number of lives you could have saved by, say, funding a water purification project. The foreground of the most looked-at painting in the museum is partly taken up by a painting seen from the back. Everything in Las Meninas seems overt and at the same time is deceptive. The mystery of what may or may not be painted on the canvas is counterpoised by the concrete evidence of its reverse, and along with it, by the irreducible material nature of the art of painting, emphasized by the scale of that enormous object made of stiff, rough cloth and wooden bars locked together firmly enough for the contraption to stand upright. Velázquez devotes as much attention to those carefully cut pieces of wood—their knots, their volume, the way the light shows them in relief, the rough texture of the cloth—as to the blond, dazzled hair of the infanta or to the butterfly, perhaps of silver filigree, that the maid María Agustina Sarmiento wears in her hair, as distinct as a piece of jewelry when seen from a distance, though it dissolves into small abstract patches of color when seen up close. Velázquez had “brushes . . . furnished with long handles,” says Palomino, “which he employed sometimes to paint from a greater distance and more boldly, so it all seemed meaningless from up close, and proved a miracle from afar.”

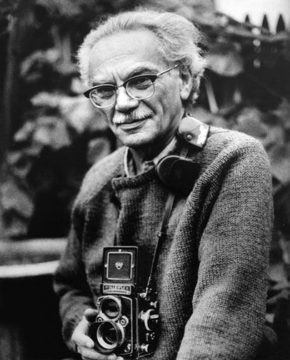

The foreground of the most looked-at painting in the museum is partly taken up by a painting seen from the back. Everything in Las Meninas seems overt and at the same time is deceptive. The mystery of what may or may not be painted on the canvas is counterpoised by the concrete evidence of its reverse, and along with it, by the irreducible material nature of the art of painting, emphasized by the scale of that enormous object made of stiff, rough cloth and wooden bars locked together firmly enough for the contraption to stand upright. Velázquez devotes as much attention to those carefully cut pieces of wood—their knots, their volume, the way the light shows them in relief, the rough texture of the cloth—as to the blond, dazzled hair of the infanta or to the butterfly, perhaps of silver filigree, that the maid María Agustina Sarmiento wears in her hair, as distinct as a piece of jewelry when seen from a distance, though it dissolves into small abstract patches of color when seen up close. Velázquez had “brushes . . . furnished with long handles,” says Palomino, “which he employed sometimes to paint from a greater distance and more boldly, so it all seemed meaningless from up close, and proved a miracle from afar.” In the early nineties, I worked briefly as an assistant editor at Aperture, a job that involved considering unsolicited submissions of photographs. It was my good fortune that one such set of submissions was delivered to the office by the photographer himself, Milton Rogovin, and his wife, Anne, a writer and teacher. They lived in Buffalo, Anne’s home town, where Milton, a Jewish New York City native, born in 1909, was once a practicing optometrist and had long been photographing residents of his adoptive city’s relatively poor neighborhoods. The Rogovins brought a batch of his recent photos, from Buffalo’s Lower West Side, near where he had an optometry practice; some of his earlier work had been published by Aperture, and I hoped the same would happen with these newer images. It didn’t happen, but a spate of books from other publishers nonetheless followed, starting in 1994, showcasing an extraordinary body of work and with it an extraordinary couple—Milton wielded the camera, but the life project that his images embodied was a joint venture of his and Anne’s.

In the early nineties, I worked briefly as an assistant editor at Aperture, a job that involved considering unsolicited submissions of photographs. It was my good fortune that one such set of submissions was delivered to the office by the photographer himself, Milton Rogovin, and his wife, Anne, a writer and teacher. They lived in Buffalo, Anne’s home town, where Milton, a Jewish New York City native, born in 1909, was once a practicing optometrist and had long been photographing residents of his adoptive city’s relatively poor neighborhoods. The Rogovins brought a batch of his recent photos, from Buffalo’s Lower West Side, near where he had an optometry practice; some of his earlier work had been published by Aperture, and I hoped the same would happen with these newer images. It didn’t happen, but a spate of books from other publishers nonetheless followed, starting in 1994, showcasing an extraordinary body of work and with it an extraordinary couple—Milton wielded the camera, but the life project that his images embodied was a joint venture of his and Anne’s. It’s safe to say that effective altruism is no longer the small, eclectic club of philosophers, charity researchers, and do-gooders it was just a decade ago. It’s an idea, and group of people, with

It’s safe to say that effective altruism is no longer the small, eclectic club of philosophers, charity researchers, and do-gooders it was just a decade ago. It’s an idea, and group of people, with  In the last week of December 1999, a group of researchers emailed their friends, colleagues, and various listservs to ask about their plans for New Year’s Eve. They recorded how big a party a person planned to attend, how much fun they expected to have, and how much time and money they would dedicate to their festivities. This survey was not, as it may seem, an endeavor to find the most raucous and decadent New Year’s Eve party—but an attempt to capture the fleeting nature of pleasure and happiness. Of the 475 people who responded in their field study,

In the last week of December 1999, a group of researchers emailed their friends, colleagues, and various listservs to ask about their plans for New Year’s Eve. They recorded how big a party a person planned to attend, how much fun they expected to have, and how much time and money they would dedicate to their festivities. This survey was not, as it may seem, an endeavor to find the most raucous and decadent New Year’s Eve party—but an attempt to capture the fleeting nature of pleasure and happiness. Of the 475 people who responded in their field study,  Elon Musk

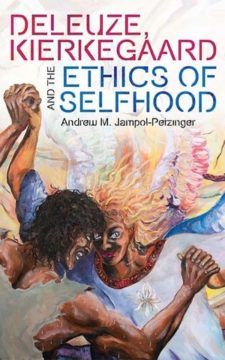

Elon Musk While there are references to Kierkegaard scattered through Gilles Louis René Deleuze’s work, these references have largely been overshadowed by the more pronounced (and less overtly ambivalent) influence of Nietzsche on Deleuze’s thought. For both, opposition to Hegel is a central theme in their thought, which for both leads to an attempt as Deleuze writes, ‘to escape the element of reflection’ (Deleuze 1994: 8). Similarly, both emphasise the importance of philosophical style, and move to indirect communication as a way of avoiding what they see as a tendency to conflate the representation of movement or becoming with becoming itself in traditional philosophical discourse. Nonetheless, there is an obvious difference between Deleuze and Kierkegaard, with Deleuze being a thoroughgoing atheist, and Kierkegaard a major theological thinker. In this book, Andrew Jampol-Petzinger focuses on the normative dimensions of both philosophers’ work, arguing that such a reading can diffuse some of the tensions between the theological positions of the two philosophers, as well as providing a corrective to some of the readings of Deleuze’s thought that emphasise the self-destructive aspect of the Deleuzian ethical project. Jampol-Petzinger addresses this through a focus on the account of the self that both philosophers develop, one that rejects a unified model of the self in favour of an account that draws out the consequences of Kant’s fracturing of the self in his paralogisms.

While there are references to Kierkegaard scattered through Gilles Louis René Deleuze’s work, these references have largely been overshadowed by the more pronounced (and less overtly ambivalent) influence of Nietzsche on Deleuze’s thought. For both, opposition to Hegel is a central theme in their thought, which for both leads to an attempt as Deleuze writes, ‘to escape the element of reflection’ (Deleuze 1994: 8). Similarly, both emphasise the importance of philosophical style, and move to indirect communication as a way of avoiding what they see as a tendency to conflate the representation of movement or becoming with becoming itself in traditional philosophical discourse. Nonetheless, there is an obvious difference between Deleuze and Kierkegaard, with Deleuze being a thoroughgoing atheist, and Kierkegaard a major theological thinker. In this book, Andrew Jampol-Petzinger focuses on the normative dimensions of both philosophers’ work, arguing that such a reading can diffuse some of the tensions between the theological positions of the two philosophers, as well as providing a corrective to some of the readings of Deleuze’s thought that emphasise the self-destructive aspect of the Deleuzian ethical project. Jampol-Petzinger addresses this through a focus on the account of the self that both philosophers develop, one that rejects a unified model of the self in favour of an account that draws out the consequences of Kant’s fracturing of the self in his paralogisms.