Editors at The Paris Review:

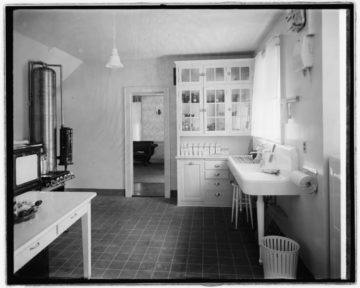

The seventies and eighties were a high point in American dance, and consequently, dance on television. As video technologies advanced, one-off performances inaccessible to most could be seamlessly captured and broadcast to the masses. Like all art forms, dance at this time was also influenced aesthetically by this new medium, as cinematic techniques permeated the choreographic (and vice versa). Today, many of these dance films are archived on YouTube. My favorite is a recording of avant-garde choreographer Blondell Cummings’s Chicken Soup, a one-woman monologue in dance that aired in 1988 on a TV program called Alive from Off Center. The piece is set to a minimalist score Cummings composed with Brian Eno and Meredith Monk. Over the music, a soft feminine voice narrates: “Coming through the open-window kitchen, all summer they drank iced coffee. With milk in it.” Cummings repeats a series of gestures: sipping coffee, threading a needle, and rocking a child. She glances with an exaggerated tilt of the head at an imaginary companion and mouths small talk—what Glenn Phillips of the Getty Museum calls her signature “facial choreography.” Her movements are sharp and distinct, creating the illusion that she is under a strobe light, or caught on slowly projected 35 mm film. She sways back and forth like a metronome, keeping time with her gestures.

The seventies and eighties were a high point in American dance, and consequently, dance on television. As video technologies advanced, one-off performances inaccessible to most could be seamlessly captured and broadcast to the masses. Like all art forms, dance at this time was also influenced aesthetically by this new medium, as cinematic techniques permeated the choreographic (and vice versa). Today, many of these dance films are archived on YouTube. My favorite is a recording of avant-garde choreographer Blondell Cummings’s Chicken Soup, a one-woman monologue in dance that aired in 1988 on a TV program called Alive from Off Center. The piece is set to a minimalist score Cummings composed with Brian Eno and Meredith Monk. Over the music, a soft feminine voice narrates: “Coming through the open-window kitchen, all summer they drank iced coffee. With milk in it.” Cummings repeats a series of gestures: sipping coffee, threading a needle, and rocking a child. She glances with an exaggerated tilt of the head at an imaginary companion and mouths small talk—what Glenn Phillips of the Getty Museum calls her signature “facial choreography.” Her movements are sharp and distinct, creating the illusion that she is under a strobe light, or caught on slowly projected 35 mm film. She sways back and forth like a metronome, keeping time with her gestures.

more here.

Farewell,

Farewell,

The alternative to war constrained by the laws of armed conflict, or

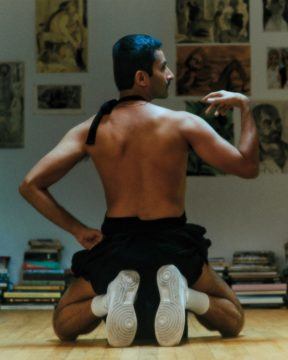

The alternative to war constrained by the laws of armed conflict, or  Three weeks before Salman Toor’s “No Ordinary Love” opened at the Baltimore Museum of Art, on May 22nd, the twenty-six paintings in the exhibition were still in his Brooklyn studio, and the largest work, “Fag Puddle with Candle, Shoe and Flag,” rested against a pillar near the center of the room. Ninety-three inches high by ninety inches wide, it is the same size, Toor told me, as Anthony van Dyck’s “Rinaldo and Armida,” a Baroque painting that is in the museum’s permanent collection. Toor had been obsessed with this picture when he was an art student. He had painted “Fag Puddle” with the idea that it would be “in conversation” with “Rinaldo and Armida,” and, while his show is on view elsewhere at the museum, the two paintings will be facing each other on opposite walls of the same Old Master gallery.

Three weeks before Salman Toor’s “No Ordinary Love” opened at the Baltimore Museum of Art, on May 22nd, the twenty-six paintings in the exhibition were still in his Brooklyn studio, and the largest work, “Fag Puddle with Candle, Shoe and Flag,” rested against a pillar near the center of the room. Ninety-three inches high by ninety inches wide, it is the same size, Toor told me, as Anthony van Dyck’s “Rinaldo and Armida,” a Baroque painting that is in the museum’s permanent collection. Toor had been obsessed with this picture when he was an art student. He had painted “Fag Puddle” with the idea that it would be “in conversation” with “Rinaldo and Armida,” and, while his show is on view elsewhere at the museum, the two paintings will be facing each other on opposite walls of the same Old Master gallery. Female white-faced capuchin monkeys living in the tropical dry forests of northwestern Costa Rica may have figured out the secret to a longer life—having fellow females as friends. “As humans, we assume there is some benefit to social interactions, but it is really hard to measure the success of our behavioral strategies,” said UCLA anthropology professor and field primatologist Susan Perry. “Why do we invest so much in our relationships with others? Does it lead to a longer lifespan? Does it lead to more reproductive success? It requires a colossal effort to measure this in humans and other animals.”

Female white-faced capuchin monkeys living in the tropical dry forests of northwestern Costa Rica may have figured out the secret to a longer life—having fellow females as friends. “As humans, we assume there is some benefit to social interactions, but it is really hard to measure the success of our behavioral strategies,” said UCLA anthropology professor and field primatologist Susan Perry. “Why do we invest so much in our relationships with others? Does it lead to a longer lifespan? Does it lead to more reproductive success? It requires a colossal effort to measure this in humans and other animals.” The role of poet-critics is a special one in any literature. Practitioners of the art, they also reveal its underpinnings, an activity that involves more than a mere thumbs-up-or-down review. Instead, by shaping whom and how we read, their influence can be considerable. Randall Jarrell famously dissected poets in regards to their best, or most often, worst tendencies. T.S. Eliot, on the other hand, took the high road, gazing calmly over the centuries while situating poets amid a cultural landscape over which he sought to reign. Usually, however, the stakes are not that high, for most often the role of the poet-critic is neither to delineate nor disseminate, but rather to illuminate. In such manner the main subject of the poet-critic, versus that of the literary critic or reviewer, is poetry itself. Reviewers tell us what a book of poems is “about”; the poet-critic reminds us of what poetry is and can be.

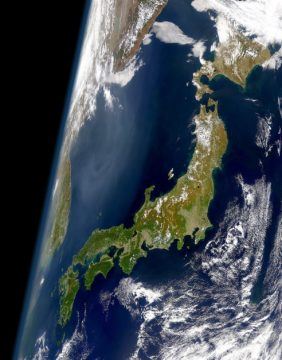

The role of poet-critics is a special one in any literature. Practitioners of the art, they also reveal its underpinnings, an activity that involves more than a mere thumbs-up-or-down review. Instead, by shaping whom and how we read, their influence can be considerable. Randall Jarrell famously dissected poets in regards to their best, or most often, worst tendencies. T.S. Eliot, on the other hand, took the high road, gazing calmly over the centuries while situating poets amid a cultural landscape over which he sought to reign. Usually, however, the stakes are not that high, for most often the role of the poet-critic is neither to delineate nor disseminate, but rather to illuminate. In such manner the main subject of the poet-critic, versus that of the literary critic or reviewer, is poetry itself. Reviewers tell us what a book of poems is “about”; the poet-critic reminds us of what poetry is and can be. Still, national images are always subject to fluctuation, and at least in the West, historical shifts in the perception of Japan have been particularly dramatic. A much darker view of the country—as a land of ferocious militarists caught up in a death cult—was already fading when I was a boy in the early postwar years. U.S. soldiers returning from Japan showed color slides of Kyoto temples and stately young women in kimonos. Soon Japan was being described as the proverbial phoenix rising from the ashes, now firmly committed to democracy and staunchly allied with its former enemy, the United States. Growing interest in Japan and Japanese culture, particularly in the late 1970s and early 1980s, led to an exaggerated picture of the nation’s strength. Admiration was mixed with misplaced envy, with “Japan Incorporated” now perceived as a new kind of Imperial Japan, with black-suited businessmen replacing sword-wielding warriors. Teaching Japanese and linguistics in a liberal-arts college in upstate New York for two years in the late 1980s, I met students eager to live in Japan long enough to master the language, obtain MBAs from a prestigious American institution, and thereby make their fortunes. Then in the early 1990s, the economic bubble burst. The rising superpower was now suddenly being described with another cliché—the land of the setting sun.

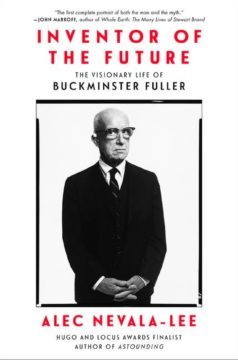

Still, national images are always subject to fluctuation, and at least in the West, historical shifts in the perception of Japan have been particularly dramatic. A much darker view of the country—as a land of ferocious militarists caught up in a death cult—was already fading when I was a boy in the early postwar years. U.S. soldiers returning from Japan showed color slides of Kyoto temples and stately young women in kimonos. Soon Japan was being described as the proverbial phoenix rising from the ashes, now firmly committed to democracy and staunchly allied with its former enemy, the United States. Growing interest in Japan and Japanese culture, particularly in the late 1970s and early 1980s, led to an exaggerated picture of the nation’s strength. Admiration was mixed with misplaced envy, with “Japan Incorporated” now perceived as a new kind of Imperial Japan, with black-suited businessmen replacing sword-wielding warriors. Teaching Japanese and linguistics in a liberal-arts college in upstate New York for two years in the late 1980s, I met students eager to live in Japan long enough to master the language, obtain MBAs from a prestigious American institution, and thereby make their fortunes. Then in the early 1990s, the economic bubble burst. The rising superpower was now suddenly being described with another cliché—the land of the setting sun. It just so happens Fuller’s popular legacy is bloated, like the geodesic domes he is most easily identified with today. Alec Nevala-Lee’s new biography, Inventor of the Future, fact-checks Fuller’s legend and then corrects the record. Nevala-Lee himself discovered Fuller through the pages of the counterculture bible, Whole Earth Catalog, and grew up admiring him. But, in writing Fuller’s biography, he resists the hypnotic whirlpool surrounding Fuller. Known to be an unreliable narrator of his own life, Fuller inflated numbers, misrepresented facts, and invented stories of epiphanies and revelations. The legends and myths solidified with their countless retellings — but, really, how dare anyone doubt a sage? He lied about high school grades he never obtained, college courses never taken, daring rescues never made, and those are just the easiest to fact-check. Whenever possible, Nevala-Lee corrects Fuller as he cites him, the embellished version followed by the correct, less glamorous version. At other times, the reader is left wondering if what’s written on the page really happened.

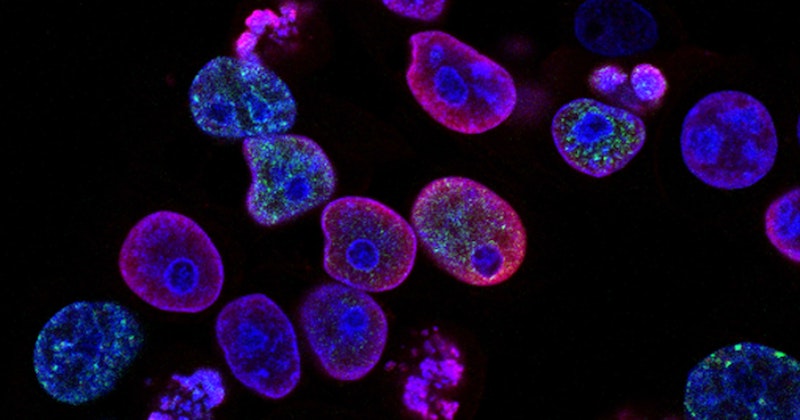

It just so happens Fuller’s popular legacy is bloated, like the geodesic domes he is most easily identified with today. Alec Nevala-Lee’s new biography, Inventor of the Future, fact-checks Fuller’s legend and then corrects the record. Nevala-Lee himself discovered Fuller through the pages of the counterculture bible, Whole Earth Catalog, and grew up admiring him. But, in writing Fuller’s biography, he resists the hypnotic whirlpool surrounding Fuller. Known to be an unreliable narrator of his own life, Fuller inflated numbers, misrepresented facts, and invented stories of epiphanies and revelations. The legends and myths solidified with their countless retellings — but, really, how dare anyone doubt a sage? He lied about high school grades he never obtained, college courses never taken, daring rescues never made, and those are just the easiest to fact-check. Whenever possible, Nevala-Lee corrects Fuller as he cites him, the embellished version followed by the correct, less glamorous version. At other times, the reader is left wondering if what’s written on the page really happened. The idea that mutations cause cancer remains the dominant paradigm. A special issue of Nature from 2020 wrote: “Cancer is a disease of the genome, caused by a cell’s acquisition of somatic mutations in key cancer genes.” Yet over the last decade it has looked as if the juggernaut has rolled too far. It has certainly failed to deliver on its promise in terms of therapies. So why hasn’t the death rate from malignant cancer changed since 1971?

The idea that mutations cause cancer remains the dominant paradigm. A special issue of Nature from 2020 wrote: “Cancer is a disease of the genome, caused by a cell’s acquisition of somatic mutations in key cancer genes.” Yet over the last decade it has looked as if the juggernaut has rolled too far. It has certainly failed to deliver on its promise in terms of therapies. So why hasn’t the death rate from malignant cancer changed since 1971?

In popular culture, Tudor noblewoman

In popular culture, Tudor noblewoman  You might think that the FBI search at Mar-a-Lago yesterday would provide a welcome opportunity for a Trump-weary Republican Party. This would be an entirely postpresidential scandal for Donald Trump. Unlike his two impeachments, this time any legal jeopardy is a purely personal Trump problem. Big donors and Fox News management have been trying for months to nudge the party away from Trump. Here was the perfect chance. Just say “No comment” and let justice take its course.

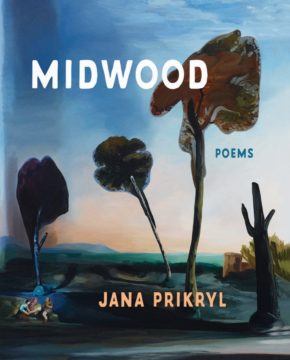

You might think that the FBI search at Mar-a-Lago yesterday would provide a welcome opportunity for a Trump-weary Republican Party. This would be an entirely postpresidential scandal for Donald Trump. Unlike his two impeachments, this time any legal jeopardy is a purely personal Trump problem. Big donors and Fox News management have been trying for months to nudge the party away from Trump. Here was the perfect chance. Just say “No comment” and let justice take its course. For artists, middle age is freighted with aesthetic drama. For poets, it’s also often a period of formal metamorphoses. Midlife crisis is a term too loaded with risible associations to be useful here. The transformation seems more a matter of taking inventory, the poet alighting on a doubt or an intuition and having a good look around. Evolutions during this period are frequent and substantial: the seriocomic alibi of Brazil in

For artists, middle age is freighted with aesthetic drama. For poets, it’s also often a period of formal metamorphoses. Midlife crisis is a term too loaded with risible associations to be useful here. The transformation seems more a matter of taking inventory, the poet alighting on a doubt or an intuition and having a good look around. Evolutions during this period are frequent and substantial: the seriocomic alibi of Brazil in