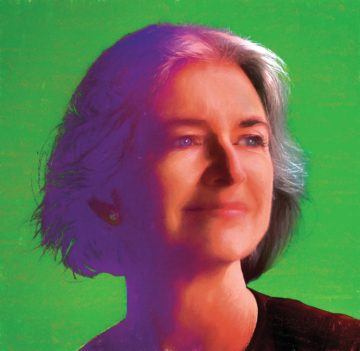

David Marchese in The New York Times:

It’s entirely possible, maybe even likely, that during some slow day at the lab early in her career, Jennifer Doudna, in a moment of private ambition, daydreamed about making a breakthrough that could change the world. But communicating with the world about the ethical ramifications of such a breakthrough? “Definitely not!” says Doudna, who along with Emmanuelle Charpentier won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2020 for their research on CRISPR gene-editing technology. “I’m still on the learning curve with that.” Since 2012, when Doudna and her colleagues shared the findings of work they did on editing bacterial genes, the 58-year-old has become a leading voice in the conversation about how we might use CRISPR — uses that could, and probably will, include tweaking crops to become more drought resistant, curing genetically inheritable medical disorders and, most controversial, editing human embryos. “It’s a little scary, quite honestly,” Doudna says about the possibilities of our CRISPR future. “But it’s also quite exciting.”

It’s entirely possible, maybe even likely, that during some slow day at the lab early in her career, Jennifer Doudna, in a moment of private ambition, daydreamed about making a breakthrough that could change the world. But communicating with the world about the ethical ramifications of such a breakthrough? “Definitely not!” says Doudna, who along with Emmanuelle Charpentier won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2020 for their research on CRISPR gene-editing technology. “I’m still on the learning curve with that.” Since 2012, when Doudna and her colleagues shared the findings of work they did on editing bacterial genes, the 58-year-old has become a leading voice in the conversation about how we might use CRISPR — uses that could, and probably will, include tweaking crops to become more drought resistant, curing genetically inheritable medical disorders and, most controversial, editing human embryos. “It’s a little scary, quite honestly,” Doudna says about the possibilities of our CRISPR future. “But it’s also quite exciting.”

More here.

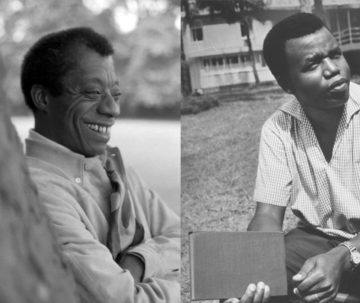

Chinua Achebe and James Baldwin met for the first time at the 1980 conference of the African Language Association in Gainesville, Florida. The historic encounter between two literary giants comes to us in poignant fragments. Achebe recalled the meeting in a 2001

Chinua Achebe and James Baldwin met for the first time at the 1980 conference of the African Language Association in Gainesville, Florida. The historic encounter between two literary giants comes to us in poignant fragments. Achebe recalled the meeting in a 2001  It’s always a little humbling to think about what affects your words and actions might have on other people, not only right now but potentially well into the future. Now take that humble feeling and promote it to all of humanity, and arbitrarily far in time. How do our actions as a society affect all the potential generations to come? William MacAskill is best known as a founder of the

It’s always a little humbling to think about what affects your words and actions might have on other people, not only right now but potentially well into the future. Now take that humble feeling and promote it to all of humanity, and arbitrarily far in time. How do our actions as a society affect all the potential generations to come? William MacAskill is best known as a founder of the  What we do now affects those future people in dramatic ways: whether they will exist at all and in what numbers; what values they embrace; what sort of planet they inherit; what sorts of lives they lead. It’s as if we’re trapped on a tiny island while our actions determine the habitability of a vast continent and the life prospects of the many who may, or may not, inhabit it. What an awful responsibility.

What we do now affects those future people in dramatic ways: whether they will exist at all and in what numbers; what values they embrace; what sort of planet they inherit; what sorts of lives they lead. It’s as if we’re trapped on a tiny island while our actions determine the habitability of a vast continent and the life prospects of the many who may, or may not, inhabit it. What an awful responsibility. When Alice Hughes downloaded a preprint from the server Research Square in September 2021, she could hardly believe her eyes. The study

When Alice Hughes downloaded a preprint from the server Research Square in September 2021, she could hardly believe her eyes. The study  Ultimately, Surrealist Sabotage presents anti-work aesthetics as a fascinating and enduring thematic in Surrealist production, yet the political stakes of this thematic remain elusive. One reason lies in the book’s tendency toward diffuse and evenhanded treatment of wide-ranging source materials, at times deflecting important nuances and contradictions among and within them. Historical tensions internal to Surrealism are sidelined, including political disagreements between Breton and other interwar Surrealist-communists like Aragon and Bataille (the latter once colorfully denounced Breton’s camp as “too many fucking idealists”). Moreover, the complexities of Soviet art’s evolving orientation toward labor—inextricable, at the time, from the unprecedented challenge of transitioning to a classless society, despite economic underdevelopment and imperialist incursions—are all but elided. Socialist art becomes something of a straw man, reduced to a wholesale celebration of labor for labor’s sake. Nevertheless, Susik succeeds in eliciting tantalizing frictions around the relation of avant-garde movements to leftist politics in her study of the Surrealists’ attempts to “reconcile their revolution of the mind with the Marxist call for a proletarian overthrow.”

Ultimately, Surrealist Sabotage presents anti-work aesthetics as a fascinating and enduring thematic in Surrealist production, yet the political stakes of this thematic remain elusive. One reason lies in the book’s tendency toward diffuse and evenhanded treatment of wide-ranging source materials, at times deflecting important nuances and contradictions among and within them. Historical tensions internal to Surrealism are sidelined, including political disagreements between Breton and other interwar Surrealist-communists like Aragon and Bataille (the latter once colorfully denounced Breton’s camp as “too many fucking idealists”). Moreover, the complexities of Soviet art’s evolving orientation toward labor—inextricable, at the time, from the unprecedented challenge of transitioning to a classless society, despite economic underdevelopment and imperialist incursions—are all but elided. Socialist art becomes something of a straw man, reduced to a wholesale celebration of labor for labor’s sake. Nevertheless, Susik succeeds in eliciting tantalizing frictions around the relation of avant-garde movements to leftist politics in her study of the Surrealists’ attempts to “reconcile their revolution of the mind with the Marxist call for a proletarian overthrow.” As someone from South China who is accustomed to humidity, the first time I went to Beijing I was struck by its dryness, especially in winter. My proximal nail folds cracked, no matter how much hand cream I put on. For Beijing citizens, sandstorms and smog are the twin horrors. One year the sandstorm was so thick it painted the sky orange. Even if you sealed all the windows, the next day your tables and floors would be covered by sand. The spring wind blows it in from the Gobi Desert. The smog, by contrast, has many culprits: fossil fuels, coal, heavy industry, too many cars. The tiny particles hang in the air waiting to be breathed in and no one can escape from it. Even the supreme leader has to breathe the same polluted air as the rest of us. People in Beijing hate the wind for bringing the sand but love it for blowing the smog away.

As someone from South China who is accustomed to humidity, the first time I went to Beijing I was struck by its dryness, especially in winter. My proximal nail folds cracked, no matter how much hand cream I put on. For Beijing citizens, sandstorms and smog are the twin horrors. One year the sandstorm was so thick it painted the sky orange. Even if you sealed all the windows, the next day your tables and floors would be covered by sand. The spring wind blows it in from the Gobi Desert. The smog, by contrast, has many culprits: fossil fuels, coal, heavy industry, too many cars. The tiny particles hang in the air waiting to be breathed in and no one can escape from it. Even the supreme leader has to breathe the same polluted air as the rest of us. People in Beijing hate the wind for bringing the sand but love it for blowing the smog away. In the designated game room at the Nugget Casino Resort in Sparks, Nevada, which was open 24 hours a day during this year’s Mensa Annual Gathering, I sat at a table with a woman named Kimberly Bakke, a 30-year-old purple-haired pastry chef and teacher from Las Vegas. Bakke is basically Mensa royalty. A 1996 Orange County Register article about her admission to the high-IQ club revealed that she was conceived at a Mensa convention, and she hasn’t missed one since; she became a member when she was three. “I have a big brain,” she told the Register reporter, who noted that her IQ was 143, about 50 points higher than the average among people of all ages. Bakke was hanging out with Christopher Whalen, a 35-year-old defense contractor from Omaha, Nebraska, who was admitted to the club in 2016. They met in a Mensa Gen-Y Facebook group shortly after, and became fast friends, texting each other every day. The 2022 Annual Gathering (AG, as Mensans call it) was Whalen’s first and marked the first time the pair met IRL.

In the designated game room at the Nugget Casino Resort in Sparks, Nevada, which was open 24 hours a day during this year’s Mensa Annual Gathering, I sat at a table with a woman named Kimberly Bakke, a 30-year-old purple-haired pastry chef and teacher from Las Vegas. Bakke is basically Mensa royalty. A 1996 Orange County Register article about her admission to the high-IQ club revealed that she was conceived at a Mensa convention, and she hasn’t missed one since; she became a member when she was three. “I have a big brain,” she told the Register reporter, who noted that her IQ was 143, about 50 points higher than the average among people of all ages. Bakke was hanging out with Christopher Whalen, a 35-year-old defense contractor from Omaha, Nebraska, who was admitted to the club in 2016. They met in a Mensa Gen-Y Facebook group shortly after, and became fast friends, texting each other every day. The 2022 Annual Gathering (AG, as Mensans call it) was Whalen’s first and marked the first time the pair met IRL. D

D Surrealism is having a moment. It is the theme of this year’s

Surrealism is having a moment. It is the theme of this year’s  “We have heard that when it arrived in Europe, zero was treated with suspicion. We don’t think of the absence of sound as a type of sound, so why should the absence of numbers be a number, argued its detractors. It took centuries for zero to gain acceptance. It is certainly not like other numbers. To work with it requires some tough intellectual contortions, as mathematician Ian Stewart explains.

“We have heard that when it arrived in Europe, zero was treated with suspicion. We don’t think of the absence of sound as a type of sound, so why should the absence of numbers be a number, argued its detractors. It took centuries for zero to gain acceptance. It is certainly not like other numbers. To work with it requires some tough intellectual contortions, as mathematician Ian Stewart explains. Donald Trump says Republican voters sent Liz Cheney to “political oblivion” with her crushing election defeat at the hands of a candidate he endorsed. But not so fast – here’s how one of the former president’s biggest critics could still hurt him if he runs for re-election.

Donald Trump says Republican voters sent Liz Cheney to “political oblivion” with her crushing election defeat at the hands of a candidate he endorsed. But not so fast – here’s how one of the former president’s biggest critics could still hurt him if he runs for re-election. More than once I’ve been told by successful writers that if I wanted to become a writer, I should copy out by hand my favorite novel. “You have to write out the entire thing,” one of them told me. “You can’t imagine how illuminating it can be.” I’ve never done this exercise myself, but I believe that I’ve experienced its intended effect doing literary translations. Translating a novel was a formative experience for me as a writer because I learned that writing is like any other art: while talent can’t be taught, technique can be learned. So, how exactly does one learn technique? I decided to take creative writing classes, earning my Certificate in Creative Writing from UCLA Extension and attending classes through Stanford Continuing Education’s program, as well as a handful of other writing centers. It was then that I experienced the creative writing workshop for myself.

More than once I’ve been told by successful writers that if I wanted to become a writer, I should copy out by hand my favorite novel. “You have to write out the entire thing,” one of them told me. “You can’t imagine how illuminating it can be.” I’ve never done this exercise myself, but I believe that I’ve experienced its intended effect doing literary translations. Translating a novel was a formative experience for me as a writer because I learned that writing is like any other art: while talent can’t be taught, technique can be learned. So, how exactly does one learn technique? I decided to take creative writing classes, earning my Certificate in Creative Writing from UCLA Extension and attending classes through Stanford Continuing Education’s program, as well as a handful of other writing centers. It was then that I experienced the creative writing workshop for myself. Even a small conflict in which two nations unleash nuclear weapons on each other could lead to worldwide famine, new research suggests. Soot from burning cities would encircle the planet and cool it by reflecting sunlight back into space. This in turn would cause global crop failures that — in a worst-case scenario — could put 5 billion people on the brink of death.

Even a small conflict in which two nations unleash nuclear weapons on each other could lead to worldwide famine, new research suggests. Soot from burning cities would encircle the planet and cool it by reflecting sunlight back into space. This in turn would cause global crop failures that — in a worst-case scenario — could put 5 billion people on the brink of death.