Jennifer Szalai in the New York Times:

As Jeff Chang puts it in “Water Mirror Echo,” his exuberant new book about Lee as both a celebrity and an Asian American, the restless actor oscillated between “follow-the-flow Zen surrender” and “sunset-chasing American ambition.” Chang gets his title from a portion of a Taoist classic, “The Liezi,” that Lee found striking enough to transcribe:

As Jeff Chang puts it in “Water Mirror Echo,” his exuberant new book about Lee as both a celebrity and an Asian American, the restless actor oscillated between “follow-the-flow Zen surrender” and “sunset-chasing American ambition.” Chang gets his title from a portion of a Taoist classic, “The Liezi,” that Lee found striking enough to transcribe:

If nothing within you stays rigid,

Outward things will disclose themselves.

Moving, be like water.

Still, be like a mirror.

Respond like an echo.

Sound advice, but for an Asian American trying to break into Hollywood, maintaining such equanimity was easier said than done. Chang, whose books include “Can’t Stop Won’t Stop,” a history of hip-hop’s early years, has written a capacious and entertaining account of Lee’s life and times. Lee, who was 32 when he suddenly died, was hard to pin down, in all senses of the word. Chang has rummaged through the archives and interviewed Lee’s surviving family members and friends; he writes with the diligence of a scholar and the propulsive energy of a fan.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

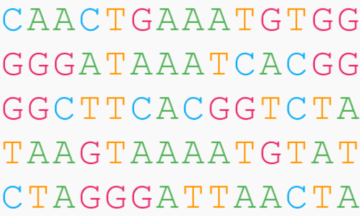

AI systems’ mastery of language may or may not portend a future of superintelligent AI minds, but it already provides a proof of concept for a revolution in gene editing. And though such a revolution promises to unlock transformative medical advancements, it also brings longstanding bioethical dilemmas to the fore: Should people of means be able to hardwire physical or cognitive advantages into their genomes, or their children’s? Where is the line between medical therapy and dehumanizing enhancements?

AI systems’ mastery of language may or may not portend a future of superintelligent AI minds, but it already provides a proof of concept for a revolution in gene editing. And though such a revolution promises to unlock transformative medical advancements, it also brings longstanding bioethical dilemmas to the fore: Should people of means be able to hardwire physical or cognitive advantages into their genomes, or their children’s? Where is the line between medical therapy and dehumanizing enhancements? W

W A

A According to the philosopher Peter Sloterdijk, the 20th century’s form of life also began with the air. Sloterdijk puts the moment at 6 p.m. on April 22, 1915, near Ypres, when a German regiment under the command of Col. Max Peterson unleashed chlorine gas in warfare for the first time. Previously, violence in war had been directed at the human body; this attack targeted the “living organism’s immersion in a breathable milieu,” as Sloterdijk writes in “

According to the philosopher Peter Sloterdijk, the 20th century’s form of life also began with the air. Sloterdijk puts the moment at 6 p.m. on April 22, 1915, near Ypres, when a German regiment under the command of Col. Max Peterson unleashed chlorine gas in warfare for the first time. Previously, violence in war had been directed at the human body; this attack targeted the “living organism’s immersion in a breathable milieu,” as Sloterdijk writes in “ The drug discovery and development landscape is plagued by inefficiency, risk and astronomical cost. Clinical success rates languish below 10%, convoluted in- and out-licensing workflows erode precious patent life, and industry estimates suggest that biopharma companies write off some $15 billion every year on deprioritized candidates. At the same time, more than 90% of oncology drugs—and a significant proportion of all therapeutics—will lose patent exclusivity within the next five years, creating a looming innovation shortfall. Partex is here to bridge that gap. As the world’s largest artificial intelligence (AI)-driven drug-asset manager, Partex supercharges pipelines, resurrects shelved compounds and slashes development time to clinic—revolutionizing discovery and development at every step.

The drug discovery and development landscape is plagued by inefficiency, risk and astronomical cost. Clinical success rates languish below 10%, convoluted in- and out-licensing workflows erode precious patent life, and industry estimates suggest that biopharma companies write off some $15 billion every year on deprioritized candidates. At the same time, more than 90% of oncology drugs—and a significant proportion of all therapeutics—will lose patent exclusivity within the next five years, creating a looming innovation shortfall. Partex is here to bridge that gap. As the world’s largest artificial intelligence (AI)-driven drug-asset manager, Partex supercharges pipelines, resurrects shelved compounds and slashes development time to clinic—revolutionizing discovery and development at every step. Open one of the drawers in a collections cabinet at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, and you’ll find a small booklet of Efka cigarette papers. The papers are part of a broader story the museum tells about Nazism, corporate collaboration, and wartime propaganda.

Open one of the drawers in a collections cabinet at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, and you’ll find a small booklet of Efka cigarette papers. The papers are part of a broader story the museum tells about Nazism, corporate collaboration, and wartime propaganda. Italy is not always the salvation of English-speaking people—but it does often seem that way. In film, in literature, in food, it’s the place where you go to find yourself. The real you, the one whose blazing depths have been obscured by the cold crust of convention. In The Enchanted April—the 1922 bestseller that turned Positano into a tourist destination—Elizabeth von Arnim suggested that the Mediterranean climate could burn off the impurities of the English soul, as if by a kind of Italian alchemy. English travelers from Byron to E. M. Forster advanced a similar sort of travel magic as a means for getting in touch with one’s soul. Keats, wracked with tuberculosis, went to Italy hoping to save his life.

Italy is not always the salvation of English-speaking people—but it does often seem that way. In film, in literature, in food, it’s the place where you go to find yourself. The real you, the one whose blazing depths have been obscured by the cold crust of convention. In The Enchanted April—the 1922 bestseller that turned Positano into a tourist destination—Elizabeth von Arnim suggested that the Mediterranean climate could burn off the impurities of the English soul, as if by a kind of Italian alchemy. English travelers from Byron to E. M. Forster advanced a similar sort of travel magic as a means for getting in touch with one’s soul. Keats, wracked with tuberculosis, went to Italy hoping to save his life. Super Agers, by clinician Eric Topol, has just been published, but it was almost surreal for me as a US scientist to read the book now, with its optimistic take on the state of the medical field. Despite their extreme promise, many of the lines of research that Topol describes have been subject to

Super Agers, by clinician Eric Topol, has just been published, but it was almost surreal for me as a US scientist to read the book now, with its optimistic take on the state of the medical field. Despite their extreme promise, many of the lines of research that Topol describes have been subject to  I meet a lot of people who don’t like their jobs, and when I ask them what they’d rather do instead, about 75% say something like, “Oh, I dunno, I’d really love to run a little coffee shop.” If I’m feeling mischievous that day, I ask them one question: “Where would you get the coffee beans?”

I meet a lot of people who don’t like their jobs, and when I ask them what they’d rather do instead, about 75% say something like, “Oh, I dunno, I’d really love to run a little coffee shop.” If I’m feeling mischievous that day, I ask them one question: “Where would you get the coffee beans?” Here’s a test for infants: Show them a glass of water on a desk. Hide it behind a wooden board. Now move the board toward the glass. If the board keeps going past the glass, as if it weren’t there, are they surprised? Many 6-month-olds are, and by a year, almost all children have an intuitive notion of an object’s permanence, learned through observation. Now some artificial intelligence models do too.

Here’s a test for infants: Show them a glass of water on a desk. Hide it behind a wooden board. Now move the board toward the glass. If the board keeps going past the glass, as if it weren’t there, are they surprised? Many 6-month-olds are, and by a year, almost all children have an intuitive notion of an object’s permanence, learned through observation. Now some artificial intelligence models do too. According to the existential-risk researcher Luke Kemp, globalization has produced a planetary “

According to the existential-risk researcher Luke Kemp, globalization has produced a planetary “ In a prescient essay published in 2000, the Princeton historian Robert Darnton – one of the grandees of the historical profession – proposed a new kind of history, one prompted as much by recent developments in Silicon Valley as anything gleaned in the archives. He called for ‘a general attack on the problem of how societies made sense of events and transmitted information about them, something that might be called the history of communication’. This, he argued, had to be much larger than just a history of newspapers. It had to encompass how information spread by word of mouth, the places where people convened to trade it and the multiple professions engaged in its dispersal.

In a prescient essay published in 2000, the Princeton historian Robert Darnton – one of the grandees of the historical profession – proposed a new kind of history, one prompted as much by recent developments in Silicon Valley as anything gleaned in the archives. He called for ‘a general attack on the problem of how societies made sense of events and transmitted information about them, something that might be called the history of communication’. This, he argued, had to be much larger than just a history of newspapers. It had to encompass how information spread by word of mouth, the places where people convened to trade it and the multiple professions engaged in its dispersal.