Justin E. H. Smith in The Hinternet:

The signaling behavior of human beings is intricate indeed. Forty years ago a man, seething with desire, issued forth a string of identical second-person singular imperatives followed by a hortatory first-person plural:

The signaling behavior of human beings is intricate indeed. Forty years ago a man, seething with desire, issued forth a string of identical second-person singular imperatives followed by a hortatory first-person plural:

Get up, get up, get up, get up, let’s make love tonight.

As far as can be determined the immediate object of desire was not in his presence at the precise moment of his yearning. He might not have had a particular object in mind at all. No one followed the command, no one “made love”, at least not right away, at least not if we exclude the very form of erotopoiesis of which the expression of yearning was already the culmination. If we know about his yearning at all this is only because it came out of him in the presence of a complex arrangement of electrical signals and magnetic tape —basic materials and principles of the physical world—, which “recorded” his voice somewhat in the way tree rings record a season’s rain, and the layers of Antarctic ice record the radioactivity of a nuclear test in the Bikini Atoll. And like radioactivity, once such yearning is caught on tape and released into the world, it is hard indeed to drive it out again.

More here.

The aim of my piece was to challenge the popular notion that mathematics is synonymous with calculation. Starting with arithmetic and proceeding through algebra and beyond, the message drummed into our heads as students is that we do math to “get the right answer.” The drill of multiplication tables, the drudgery of long division, the quadratic formula and its memorization—these are the dreary memories many of us carry around from school as a result.

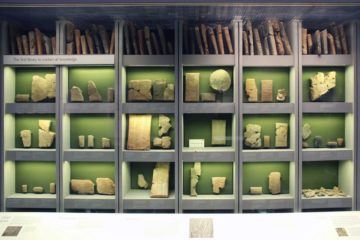

The aim of my piece was to challenge the popular notion that mathematics is synonymous with calculation. Starting with arithmetic and proceeding through algebra and beyond, the message drummed into our heads as students is that we do math to “get the right answer.” The drill of multiplication tables, the drudgery of long division, the quadratic formula and its memorization—these are the dreary memories many of us carry around from school as a result. The recent debate over “presentism” among historians, especially those based in the United States, has generated both heat and light. It is a useful conversation to have now, at a moment when the public sphere, and even more so the university’s space within it, seems to consist more of mines than of fields. Debates about Covid-19, affirmative (in)action, antisemitism, sexual violence, student debt, Title IX, Confederate monuments, racist donors, resigning presidents, and rogue trustees combine to occlude the daylight of classes, books, and learning.

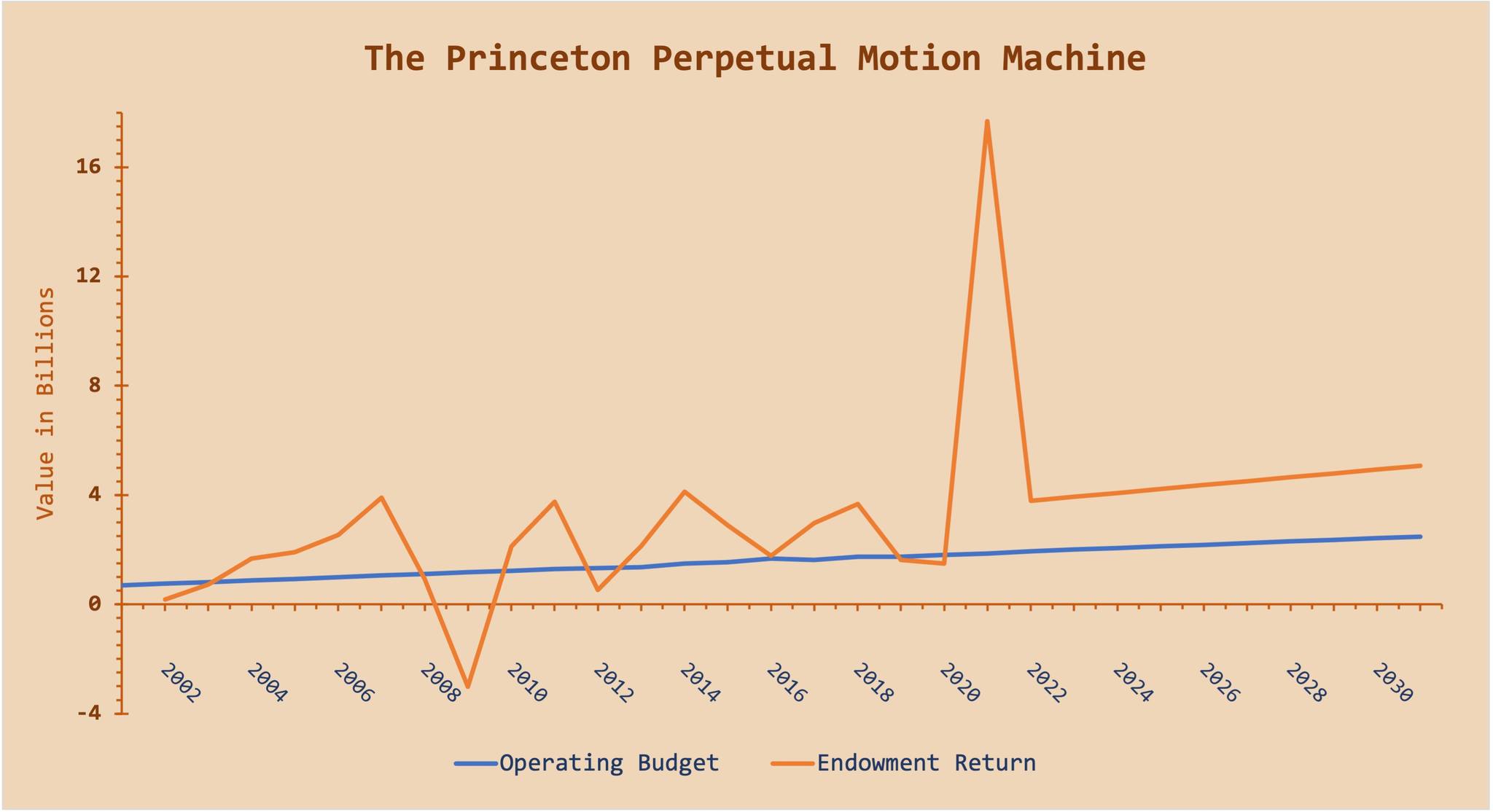

The recent debate over “presentism” among historians, especially those based in the United States, has generated both heat and light. It is a useful conversation to have now, at a moment when the public sphere, and even more so the university’s space within it, seems to consist more of mines than of fields. Debates about Covid-19, affirmative (in)action, antisemitism, sexual violence, student debt, Title IX, Confederate monuments, racist donors, resigning presidents, and rogue trustees combine to occlude the daylight of classes, books, and learning. After a stellar year in 2021, Princeton University has an endowment of $37.7 billion. Over the past 20 years, the average annual return for the endowment has been 11.2 percent. Let us give Princeton the benefit of the doubt and assume that at least some of that was luck and maybe unsustainable, and that a more reasonable prediction going forward would be that Princeton can average a return on its investments of an even 10 percent a year. That puts Princeton’s endowment return next year at roughly $3.77 billion.

After a stellar year in 2021, Princeton University has an endowment of $37.7 billion. Over the past 20 years, the average annual return for the endowment has been 11.2 percent. Let us give Princeton the benefit of the doubt and assume that at least some of that was luck and maybe unsustainable, and that a more reasonable prediction going forward would be that Princeton can average a return on its investments of an even 10 percent a year. That puts Princeton’s endowment return next year at roughly $3.77 billion. “D

“D Zan, Zendegi, Azadi: Woman! Life! Freedom!

Zan, Zendegi, Azadi: Woman! Life! Freedom! Alden Young in Phenomenal World:

Alden Young in Phenomenal World: Stephen Ornes in Quanta:

Stephen Ornes in Quanta: Kahled Talaat in Tablet (photo by Stefan Sauer/Picture Alliance via Getty Images)

Kahled Talaat in Tablet (photo by Stefan Sauer/Picture Alliance via Getty Images) His fingernails are ragged. He wears designer suits but his choice of underwear, cheap Russian tighty-whities, is poignant. When he gets drunk, he talks about Stalin. He likes the dumbest game shows. Maybe he’s K.G.B. He does not know how to unfasten garters.

His fingernails are ragged. He wears designer suits but his choice of underwear, cheap Russian tighty-whities, is poignant. When he gets drunk, he talks about Stalin. He likes the dumbest game shows. Maybe he’s K.G.B. He does not know how to unfasten garters. How to walk properly, according to Lorraine O’Grady, the eighty-eight-year-old conceptual and performance artist: “With your chin tucked under your head, your shoulders dropped down, your stomach pulled up.” Good posture has become a concern for O’Grady in the past couple of years, as her latest persona, the Knight, is a character that requires her to wear a forty-pound suit of armor. “As long as I don’t gain or lose more than three or four pounds, I’m O.K.,” O’Grady told me in late August, over Zoom, while we discussed “Greetings and Theses,” the fourteen-minute film that constituted the official performance début of the Knight. The première was held, in late July, at the Brooklyn Museum, the site of the 2021 exhibition “

How to walk properly, according to Lorraine O’Grady, the eighty-eight-year-old conceptual and performance artist: “With your chin tucked under your head, your shoulders dropped down, your stomach pulled up.” Good posture has become a concern for O’Grady in the past couple of years, as her latest persona, the Knight, is a character that requires her to wear a forty-pound suit of armor. “As long as I don’t gain or lose more than three or four pounds, I’m O.K.,” O’Grady told me in late August, over Zoom, while we discussed “Greetings and Theses,” the fourteen-minute film that constituted the official performance début of the Knight. The première was held, in late July, at the Brooklyn Museum, the site of the 2021 exhibition “ There was no fanfare when “The Waste Land” first arrived. It was printed in the inaugural issue of The Criterion, a quarterly journal, in October, 1922. On the front cover was a hefty list of contents, among them a review by Hermann Hesse of recent German poetry; an article on James Joyce’s “

There was no fanfare when “The Waste Land” first arrived. It was printed in the inaugural issue of The Criterion, a quarterly journal, in October, 1922. On the front cover was a hefty list of contents, among them a review by Hermann Hesse of recent German poetry; an article on James Joyce’s “ The typical “nuclear bro” is lurking in the comments section of a clean energy YouTube video, wondering why the creator didn’t mention #nuclear. He is marching in Central California to oppose the closing of the state’s Diablo Canyon nuclear power plant. His Twitter name includes an emoji of an atom ⚛️. He might even believe that 100 percent of the world’s electricity should come from nuclear power plants. As a warming world searches for ever more abundant forms of clean energy, an increasingly loud internet subculture has emerged to make the case for nuclear. They are often — but not always — men. They include grass-roots organizers and famous techno-optimists like Bill Gates and Elon Musk. And they are uniformly convinced that the world is sleeping on nuclear energy.

The typical “nuclear bro” is lurking in the comments section of a clean energy YouTube video, wondering why the creator didn’t mention #nuclear. He is marching in Central California to oppose the closing of the state’s Diablo Canyon nuclear power plant. His Twitter name includes an emoji of an atom ⚛️. He might even believe that 100 percent of the world’s electricity should come from nuclear power plants. As a warming world searches for ever more abundant forms of clean energy, an increasingly loud internet subculture has emerged to make the case for nuclear. They are often — but not always — men. They include grass-roots organizers and famous techno-optimists like Bill Gates and Elon Musk. And they are uniformly convinced that the world is sleeping on nuclear energy. Climate change is a planetary emergency. We have to do something now — but what? Saul Griffith, an inventor and renewable electricity advocate (and a recipient of a MacArthur “genius” grant), has a plan. In his book “Electrify,” Griffith lays out a detailed blueprint for fighting climate change while creating millions of new jobs and a healthier environment. Griffith’s plan can be summed up simply: Electrify everything. He explains exactly what it would take to transform our infrastructure, update our grid, and adapt our households to make this possible. Billionaires may contemplate escaping our worn-out planet on a private rocket ship to Mars, but the rest of us, Griffith says, will stay and fight for the future.

Climate change is a planetary emergency. We have to do something now — but what? Saul Griffith, an inventor and renewable electricity advocate (and a recipient of a MacArthur “genius” grant), has a plan. In his book “Electrify,” Griffith lays out a detailed blueprint for fighting climate change while creating millions of new jobs and a healthier environment. Griffith’s plan can be summed up simply: Electrify everything. He explains exactly what it would take to transform our infrastructure, update our grid, and adapt our households to make this possible. Billionaires may contemplate escaping our worn-out planet on a private rocket ship to Mars, but the rest of us, Griffith says, will stay and fight for the future.