Glioblastoma: Starlight

—for Adam

Astrocytes in the brain seem as numerous

and shapely as stars in the universe,

but when the stars in your brain go awry,

they behave like dark energy, changing

the shape of time.

You see time’s boundaries. Constraints

get into your blood and bones,

a double-barreled two years of choices

to make on days you are able make them.

You’re un-glued and re-glued in an instant,

and everything’s palliative after.

That cloak of care is another kind

of starlight, and it’s all surgery and radiation

by which you discern what’s what.

What had been an idea of happiness

by which you tried

to live becomes this moment

and the next and the need to nap

and weep, the want of words, the memory

of magic that each friend

bequeaths in your mind, however

small, the need

to father finitely and

to love for all the time in the world.

by Anna Leahy

from Contrary Magazine

If rock and roll has, in fact, become an invalidated form, a “niche product,” encrusted with its political difficulties, and, perhaps, exhausted as a way of thinking about popular music, one of the chief problems, perhaps, is that it has failed to find new ways to use the guitar. Since the high period of guitar innovation—the period in which we had Sonic Youth and their tunings, James “Blood” Ulmer and his unison strings, and the pieces for a hundred guitars of Rhys Chatham and Glenn Branca—there just hasn’t been as much innovation in the guitar as in the years prior (rare exceptions: left-field employment of guitar synthesizers in, e.g., the work of Robert Fripp, or: the beautiful jazz-flavored modulations of Marc Ribot, or: almost everything played by Nels Cline). So it’s striking and, well, thrilling, when a contemporary player appears, rises up from out of the surface noise, and seems to have his ears fixed mightily on the history of the guitar, and with it the potential for rock and roll to speak anew to an audience. Chris Forsyth is one such contemporary player. His point of origin is (arguably) New York punk of the Dolls, Television, Patti Smith group variety, but he also mixes in a kind of jam-oriented approach that would have been somewhat verboten in the orthodox punk days.

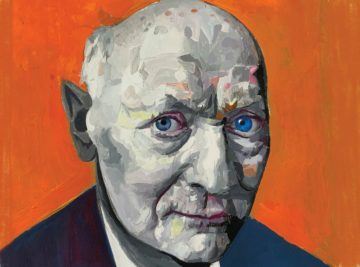

If rock and roll has, in fact, become an invalidated form, a “niche product,” encrusted with its political difficulties, and, perhaps, exhausted as a way of thinking about popular music, one of the chief problems, perhaps, is that it has failed to find new ways to use the guitar. Since the high period of guitar innovation—the period in which we had Sonic Youth and their tunings, James “Blood” Ulmer and his unison strings, and the pieces for a hundred guitars of Rhys Chatham and Glenn Branca—there just hasn’t been as much innovation in the guitar as in the years prior (rare exceptions: left-field employment of guitar synthesizers in, e.g., the work of Robert Fripp, or: the beautiful jazz-flavored modulations of Marc Ribot, or: almost everything played by Nels Cline). So it’s striking and, well, thrilling, when a contemporary player appears, rises up from out of the surface noise, and seems to have his ears fixed mightily on the history of the guitar, and with it the potential for rock and roll to speak anew to an audience. Chris Forsyth is one such contemporary player. His point of origin is (arguably) New York punk of the Dolls, Television, Patti Smith group variety, but he also mixes in a kind of jam-oriented approach that would have been somewhat verboten in the orthodox punk days. What, exactly, is David Bentley Hart’s deal? One asks the question in awe. How does he produce so many books—as of this writing, eighteen of them, spanning theology, cultural criticism, and fiction, not counting his translation of the New Testament, his co-translation with John R. Betz of Erich Przywara’s Analogia Entis, his uncollected articles (there must still be a few) and his Substack posts? When did he have time to learn so many languages, that he can refer familiarly to the literatures of Europe, China, Japan, India, and the Americas, and to fine details of theological controversy in several faiths? Where does he find a moment to floss, to do housework, to keep up with his beloved Baltimore Orioles?

What, exactly, is David Bentley Hart’s deal? One asks the question in awe. How does he produce so many books—as of this writing, eighteen of them, spanning theology, cultural criticism, and fiction, not counting his translation of the New Testament, his co-translation with John R. Betz of Erich Przywara’s Analogia Entis, his uncollected articles (there must still be a few) and his Substack posts? When did he have time to learn so many languages, that he can refer familiarly to the literatures of Europe, China, Japan, India, and the Americas, and to fine details of theological controversy in several faiths? Where does he find a moment to floss, to do housework, to keep up with his beloved Baltimore Orioles? My house is isolated, up on the tip of a hill overlooking the Mediterranean Sea, but daybreak sounds rise and reach my window, where I sit reading your book. Someone heckles from a road below to someone else, whom I imagine is trudging uphill. I recognize the Arabic words individually, but strung together, they are senseless to me. I write them down, a small digitalized scribble, on the concluding page of your book, and I mouth them repeatedly, as I do with any new word or phrase in this place, which is also new to me, to cast them in memory. Later, I’ll find someone kind enough to attempt a translation. You would know, Noor, that street calls show for nothing in the online Arabic-to-English dictionary — and that there is a particular kind of angst, a wanting and waiting, at the periphery of a language.

My house is isolated, up on the tip of a hill overlooking the Mediterranean Sea, but daybreak sounds rise and reach my window, where I sit reading your book. Someone heckles from a road below to someone else, whom I imagine is trudging uphill. I recognize the Arabic words individually, but strung together, they are senseless to me. I write them down, a small digitalized scribble, on the concluding page of your book, and I mouth them repeatedly, as I do with any new word or phrase in this place, which is also new to me, to cast them in memory. Later, I’ll find someone kind enough to attempt a translation. You would know, Noor, that street calls show for nothing in the online Arabic-to-English dictionary — and that there is a particular kind of angst, a wanting and waiting, at the periphery of a language. Recently, after a week in which

Recently, after a week in which  Thousands of Egyptians are demanding the repatriation of the Rosetta Stone from the British Museum back to its home country. The iconic artifact, which helped scientists finally decode Egyptian hieroglyphs almost exactly 200 years ago, has been in English hands since Napoleon gave it up – as well as 16 other artifacts – as part of the Treaty of Alexandria in 1801. The latest campaign to reclaim the antiquities has gathered more than 2,500 signatures in an

Thousands of Egyptians are demanding the repatriation of the Rosetta Stone from the British Museum back to its home country. The iconic artifact, which helped scientists finally decode Egyptian hieroglyphs almost exactly 200 years ago, has been in English hands since Napoleon gave it up – as well as 16 other artifacts – as part of the Treaty of Alexandria in 1801. The latest campaign to reclaim the antiquities has gathered more than 2,500 signatures in an  The brain’s lifeline, its network of blood vessels, is like a tree, says Mathieu Pernot, deputy director of the Physics for Medicine Paris Lab. The trunk begins in the neck with the carotid arteries, a pair of broad channels that then split into branches that climb into the various lobes of the brain. These channels fork endlessly into a web of tiny vessels that form a kind of canopy. The narrowest of these vessels are only wide enough for a single red blood cell to pass through, and in one important sense these vessels are akin to the tree’s leaves.

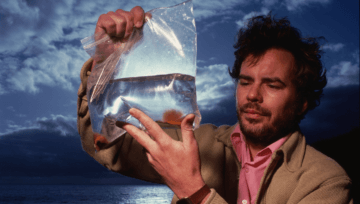

The brain’s lifeline, its network of blood vessels, is like a tree, says Mathieu Pernot, deputy director of the Physics for Medicine Paris Lab. The trunk begins in the neck with the carotid arteries, a pair of broad channels that then split into branches that climb into the various lobes of the brain. These channels fork endlessly into a web of tiny vessels that form a kind of canopy. The narrowest of these vessels are only wide enough for a single red blood cell to pass through, and in one important sense these vessels are akin to the tree’s leaves. Loretta Lynn

Loretta Lynn B

B “Remember / you can have what you ask for, ask for / everything.” In these, probably the most famous lines from Revolutionary Letters, Diane di Prima echoes Frank O’Hara’s assertion in his “Ode to Joy” that “We shall have everything we want and there’ll be no more dying.” Like her friend Frank, di Prima is writing about joy, “which will remake the world.”

“Remember / you can have what you ask for, ask for / everything.” In these, probably the most famous lines from Revolutionary Letters, Diane di Prima echoes Frank O’Hara’s assertion in his “Ode to Joy” that “We shall have everything we want and there’ll be no more dying.” Like her friend Frank, di Prima is writing about joy, “which will remake the world.” Altruistic behavior toward one’s offspring or other kin is not terribly puzzling since they are genetically related. More puzzling was the development of altruistic behavior toward unrelated others, which does appear to be antithetical to the basic, self-serving fitness interest that underlies evolutionary theory. However, Robert Trivers, in what quickly came to be considered a

Altruistic behavior toward one’s offspring or other kin is not terribly puzzling since they are genetically related. More puzzling was the development of altruistic behavior toward unrelated others, which does appear to be antithetical to the basic, self-serving fitness interest that underlies evolutionary theory. However, Robert Trivers, in what quickly came to be considered a  These days automated systems have replaced secret agents. The protagonists of state-sanctioned surveillance are cybersecurity experts hacking into smart phones’ operating systems from a suburban office park, Microsoft engineers refining a biometric camera’s algorithm from their home office, and plain-clothes soldiers parsing through geolocation data for someone else to carry out a drone strike. Most of the people involved are not called agents or spies. They are product managers, engineers, data analysts, or “intelligence researchers.” Often their work feels so ordinary they might forget they are in the business of espionage. Sometimes they might not even realize it to begin with.

These days automated systems have replaced secret agents. The protagonists of state-sanctioned surveillance are cybersecurity experts hacking into smart phones’ operating systems from a suburban office park, Microsoft engineers refining a biometric camera’s algorithm from their home office, and plain-clothes soldiers parsing through geolocation data for someone else to carry out a drone strike. Most of the people involved are not called agents or spies. They are product managers, engineers, data analysts, or “intelligence researchers.” Often their work feels so ordinary they might forget they are in the business of espionage. Sometimes they might not even realize it to begin with. For more than two decades,

For more than two decades,