Sadie Stein at The Paris Review:

One Monday evening some five years ago, I walked into my first Spiritualist service. In those days, the New York Spiritualist Church held services roughly once a month in a broad-minded white-marble Methodist structure designed to hold some thousand parishioners. But the Spiritualists only filled the first few rows. It was dim, churchy-smelling, and vast.

One Monday evening some five years ago, I walked into my first Spiritualist service. In those days, the New York Spiritualist Church held services roughly once a month in a broad-minded white-marble Methodist structure designed to hold some thousand parishioners. But the Spiritualists only filled the first few rows. It was dim, churchy-smelling, and vast.

I’d thought about what to wear. It was, after all, a church; it was also seven in the evening in late November. In the end, I changed out of my jeans and wore a high-necked Laura Ashley dress and a tweed jacket and my least ironic glasses. My hair was severely curtailed into a topknot. I suppose, as in many such moments, I was trying to control the one thing I could. As it turned out, I could have worn anything. There were people in jeans, there were people in gowns, there was a Guardian Angel beret—or maybe it was just a red hat.

more here.

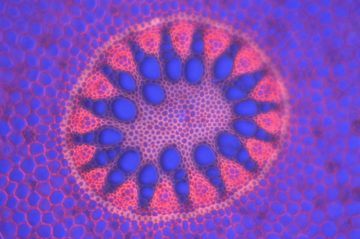

Justine Karst, a mycologist at the University of Alberta, feared things had gone too far when her son got home from eighth grade and told her he had learned that trees could talk to each other through underground networks. Her colleague, Jason Hoeksema of the University of Mississippi, had a similar feeling when watching an episode of “Ted Lasso” in which one soccer coach told another that trees in a forest cooperated rather than competed for resources.

Justine Karst, a mycologist at the University of Alberta, feared things had gone too far when her son got home from eighth grade and told her he had learned that trees could talk to each other through underground networks. Her colleague, Jason Hoeksema of the University of Mississippi, had a similar feeling when watching an episode of “Ted Lasso” in which one soccer coach told another that trees in a forest cooperated rather than competed for resources. The philosopher Stanley Cavell, who was the author of some 19 books, passed away in 2018. Fifteen years earlier, he had turned his attention to his death in Little Did I Know, a memoir occasioned by the discovery of his own declining health. There, as in much of his work, he was comfortable writing in the retrospective mode, reflecting again and again on his most famous collection of essays, Must We Mean What We Say? (1969), and the arguments, ideas, and distinctive style he developed there. The latter would be described by his critics as self-indulgent and by his defenders as profound. The reality was somewhere between these judgments, although often closer to the former than the latter.

The philosopher Stanley Cavell, who was the author of some 19 books, passed away in 2018. Fifteen years earlier, he had turned his attention to his death in Little Did I Know, a memoir occasioned by the discovery of his own declining health. There, as in much of his work, he was comfortable writing in the retrospective mode, reflecting again and again on his most famous collection of essays, Must We Mean What We Say? (1969), and the arguments, ideas, and distinctive style he developed there. The latter would be described by his critics as self-indulgent and by his defenders as profound. The reality was somewhere between these judgments, although often closer to the former than the latter. As an evolutionary biologist, I am quite used to attempts to censor research and suppress knowledge. But for most of my career, that kind of behavior came from the right. In the old days, most students and administrators were actually on our side; we were aligned against creationists. Now, the threat comes mainly from the left.

As an evolutionary biologist, I am quite used to attempts to censor research and suppress knowledge. But for most of my career, that kind of behavior came from the right. In the old days, most students and administrators were actually on our side; we were aligned against creationists. Now, the threat comes mainly from the left. It isn’t just pundits and commentators who are annoyed with the state of macro; economists in other fields often join in the criticism. For example, here’s

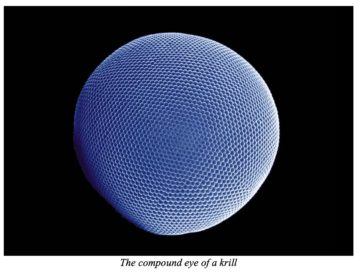

It isn’t just pundits and commentators who are annoyed with the state of macro; economists in other fields often join in the criticism. For example, here’s  One of the last flashes of creativity I saw before I deactivated my Twitter account (more on that below, and on its significance for this Substack project), was a question launched by another user (whom I can’t locate now, without Twitter, but to whom I say “thanks”). “Are there,” this user asked, “more eyes or legs in the world?”

One of the last flashes of creativity I saw before I deactivated my Twitter account (more on that below, and on its significance for this Substack project), was a question launched by another user (whom I can’t locate now, without Twitter, but to whom I say “thanks”). “Are there,” this user asked, “more eyes or legs in the world?” Moving to daylight saving time permanently could prevent 36,550 deer deaths, 33 human deaths and $1.19 billion in costs annually in the US.

Moving to daylight saving time permanently could prevent 36,550 deer deaths, 33 human deaths and $1.19 billion in costs annually in the US. People have a complicated relationship to mathematics. We all use it in our everyday lives, from calculating a tip at a restaurant to estimating the probability of some future event. But many people find the subject intimidating, if not off-putting. John Allen Paulos has long been working to make mathematics more approachable and encourage people to become more numerate. We talk about how people think about math, what kinds of math they should know, and the role of stories and narrative to make math come alive.

People have a complicated relationship to mathematics. We all use it in our everyday lives, from calculating a tip at a restaurant to estimating the probability of some future event. But many people find the subject intimidating, if not off-putting. John Allen Paulos has long been working to make mathematics more approachable and encourage people to become more numerate. We talk about how people think about math, what kinds of math they should know, and the role of stories and narrative to make math come alive. So can we find final value in the world? I believe that we can, so long as we are attuned to aesthetic value. Aesthetic value is a catch-all term that encompasses the beautiful, the ugly, the sublime, the dramatic, the comic, the cute, the kitsch, the uncanny, and many other related concepts. It is a well-worn cliché that the practical person scorns aesthetic value. But there’s reason to think that it is the only way in which we can draw final positive value from the entire world. Thus, to the extent that we care whether or not we live in a good world, we must be aesthetically sensitive.

So can we find final value in the world? I believe that we can, so long as we are attuned to aesthetic value. Aesthetic value is a catch-all term that encompasses the beautiful, the ugly, the sublime, the dramatic, the comic, the cute, the kitsch, the uncanny, and many other related concepts. It is a well-worn cliché that the practical person scorns aesthetic value. But there’s reason to think that it is the only way in which we can draw final positive value from the entire world. Thus, to the extent that we care whether or not we live in a good world, we must be aesthetically sensitive. BEING A TRUTH-TELLING

BEING A TRUTH-TELLING “Undine Spragg—how can you?” her mother wailed, raising a prematurely-wrinkled hand heavy with rings to defend the note which a languid “bell-boy” had just brought in.

“Undine Spragg—how can you?” her mother wailed, raising a prematurely-wrinkled hand heavy with rings to defend the note which a languid “bell-boy” had just brought in. T

T