Freya Johnston in Prospect Magazine:

Andrea Wulf’s substantial yet pacey new book concerns itself with a dazzling generation of German philosophers, scientists and poets who between the late 18th and early 19th centuries gathered in the provincial town of Jena and produced some of the most memorable works of European romanticism.

Andrea Wulf’s substantial yet pacey new book concerns itself with a dazzling generation of German philosophers, scientists and poets who between the late 18th and early 19th centuries gathered in the provincial town of Jena and produced some of the most memorable works of European romanticism.

Perhaps the most wonderful account of this group’s intellectual and emotional life published in English is Penelope Fitzgerald’s 1995 historical novel The Blue Flower. For that book’s epigraph, Fitzgerald chose a comment made by Friedrich von Hardenberg, the man later known as Novalis: “Novels arise out of the shortcomings of history.” This fragmentary thought is both allusive and cryptic. We might take it to mean that novels pick up where history leaves off; that fiction comes into being in order to chart the private, intimate, domestic aspects of life rather than the large-scale, public sweep of grand events that governs a conventional historical narrative. Novels implicitly challenge the priorities of history, inviting us to look within and to reconceive the world. Novalis, himself a wildly experimental writer of fiction and a poetic thinker of terrific originality and insight, argued strenuously for the need to romanticise and revolutionise our surroundings according to what we find inside ourselves: philosophy, he said, originates in feeling.

Fitzgerald’s response as a novelist to that call—to recognise the primacy of individual sensations—was to write in such an unobtrusively informed and tactful way as to convince us that she personally knew the characters about whom she was writing. Conveying her sense of the past through beautifully assured, delicately economical glimpses of the Hardenbergs and their circle at home in the 1790s, her style is as clipped and fragmentary as that of her philosophical subject, intimating via imaginary reconstructions a world of familiarity with private love, pain and grief.

More here.

Judging by the titles of bills they propose, members of Congress occupy a space between used-car salesperson and poet. Over the past two years, lawmakers in the 117th Congress have introduced the

Judging by the titles of bills they propose, members of Congress occupy a space between used-car salesperson and poet. Over the past two years, lawmakers in the 117th Congress have introduced the  A

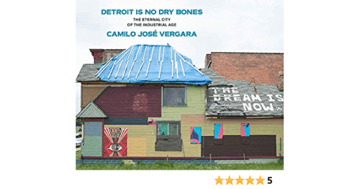

A Vergara’s newest book, Detroit Is No Dry Bones, powerfully documents the transformation of Detroit over the last several decades, offering an unflinching portrayal of a city gutted by decades of anti-urban public policies, intense racial segregation, and heartlessly mobile capital. Vergara’s approach is a reminder of the power of looking at small things—a fence, a broken window, a graffiti-strewn brick wall, a lawn ornament—to illustrate what might otherwise be impersonal processes and grand social forces. But Vergara’s keen eye also sees what cannot simply be reduced to urban decay. A raggedy lot becomes a lush garden, a blank wall becomes a canvas for an unknown artist, a pile of tires and a piece of wood become an impromptu bench at a bus stop. Vergara’s Detroit is not simply an acropolis, it is a place of rebirth and reinvention.

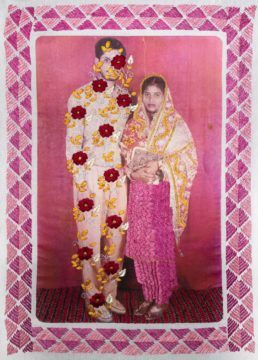

Vergara’s newest book, Detroit Is No Dry Bones, powerfully documents the transformation of Detroit over the last several decades, offering an unflinching portrayal of a city gutted by decades of anti-urban public policies, intense racial segregation, and heartlessly mobile capital. Vergara’s approach is a reminder of the power of looking at small things—a fence, a broken window, a graffiti-strewn brick wall, a lawn ornament—to illustrate what might otherwise be impersonal processes and grand social forces. But Vergara’s keen eye also sees what cannot simply be reduced to urban decay. A raggedy lot becomes a lush garden, a blank wall becomes a canvas for an unknown artist, a pile of tires and a piece of wood become an impromptu bench at a bus stop. Vergara’s Detroit is not simply an acropolis, it is a place of rebirth and reinvention. The images are printed on khadi, the cloth produced by traditional spinning wheels—the charkha, a device that is deeply rooted in Indian history. During the struggle for independence, Mahatma Gandhi used the spinning wheel as a symbol of self-reliance, urging Indians to spin their own cloth as a means of gaining economic freedom from the exploitation of British colonizers. If the spinning wheel has come to be a symbol of self-reliance, then in the work of Malik, the act of embroidery embodies resistance and the strength and care that can be found in community. Behind the work lies the reality of the struggle for women’s rights and the issue of gendered violence in India.

The images are printed on khadi, the cloth produced by traditional spinning wheels—the charkha, a device that is deeply rooted in Indian history. During the struggle for independence, Mahatma Gandhi used the spinning wheel as a symbol of self-reliance, urging Indians to spin their own cloth as a means of gaining economic freedom from the exploitation of British colonizers. If the spinning wheel has come to be a symbol of self-reliance, then in the work of Malik, the act of embroidery embodies resistance and the strength and care that can be found in community. Behind the work lies the reality of the struggle for women’s rights and the issue of gendered violence in India. In 1978, when

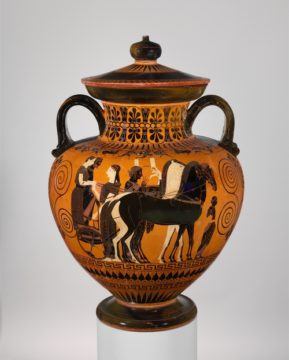

In 1978, when  There are distinct signs that the poet John Keats’ Grecian Urn has found its voice again. This is a surprise. The final Delphic utterance of the decorated vessel in his poem Ode to a Grecian Urn runs: “Beauty is Truth, Truth Beauty, — that is all / Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know.” Though well-known as verse, it has long been relegated to romantic wishful thinking.

There are distinct signs that the poet John Keats’ Grecian Urn has found its voice again. This is a surprise. The final Delphic utterance of the decorated vessel in his poem Ode to a Grecian Urn runs: “Beauty is Truth, Truth Beauty, — that is all / Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know.” Though well-known as verse, it has long been relegated to romantic wishful thinking. Artificial intelligence can learn and remember how to do multiple tasks by mimicking the way sleep helps us cement what we learned during waking hours.

Artificial intelligence can learn and remember how to do multiple tasks by mimicking the way sleep helps us cement what we learned during waking hours. The morning after the 2016 U.S. presidential election, my partner Skyped her parents back home in Italy. I finished my coffee, and they chatted. At some point her mother asked where I was: I had broken my usual pattern of dropping in to say ciao. My partner slid the laptop over to direct the camera’s gaze at my head, slumped onto our dining room table. “What happened?” the voice on the computer asked. “Trump won,” I explained.

The morning after the 2016 U.S. presidential election, my partner Skyped her parents back home in Italy. I finished my coffee, and they chatted. At some point her mother asked where I was: I had broken my usual pattern of dropping in to say ciao. My partner slid the laptop over to direct the camera’s gaze at my head, slumped onto our dining room table. “What happened?” the voice on the computer asked. “Trump won,” I explained. For me, and for many others, encountering Mark Fisher’s Capitalist Realism in 2009 felt like coming up for air. In a society where everything was arranged to make you think that emotional well-being began and ended with your own personal psychodrama, perhaps the most important thing Capitalist Realism did was to suggest that mental suffering might have something to do with structural flaws in society as a whole. In a political system which endlessly promoted the notion that we were all alone, Fisher’s book announced that we were suffering together. Also, more hopefully, it said that if we were to realise this, and somehow make connections between our several hardships, we would be taking the first step towards doing something we seemed to have mostly forgotten about by the late Noughties: mounting an organised resistance. This is the near-spiritual message in the short, sharp text of Capitalist Realism, published on the eve of a new and tumultuous decade. Whatever political and theoretical nuances it might otherwise have implied, this was a book which called for a joining of human hands.

For me, and for many others, encountering Mark Fisher’s Capitalist Realism in 2009 felt like coming up for air. In a society where everything was arranged to make you think that emotional well-being began and ended with your own personal psychodrama, perhaps the most important thing Capitalist Realism did was to suggest that mental suffering might have something to do with structural flaws in society as a whole. In a political system which endlessly promoted the notion that we were all alone, Fisher’s book announced that we were suffering together. Also, more hopefully, it said that if we were to realise this, and somehow make connections between our several hardships, we would be taking the first step towards doing something we seemed to have mostly forgotten about by the late Noughties: mounting an organised resistance. This is the near-spiritual message in the short, sharp text of Capitalist Realism, published on the eve of a new and tumultuous decade. Whatever political and theoretical nuances it might otherwise have implied, this was a book which called for a joining of human hands. J

J As I stand on the blue bridge, gateway to a subtropical garden on this island haven near southwestern England, I look to the side and see a small creature sitting astride a mound of hazelnuts. Its fur blazes a bright russet color, its tail fanned out like a sail. I glance up, and in the neighboring pine tree I see two or three more, racing up and down the trunk, pausing every so often to steal a glance at the feast below, waiting their turn. These are red squirrels, and to see them in the wild, let alone in such numbers, is a rare treat. The animals were once common throughout the United Kingdom, but the invasive gray squirrel has pushed them to the brink of extinction in all but a few strongholds.

As I stand on the blue bridge, gateway to a subtropical garden on this island haven near southwestern England, I look to the side and see a small creature sitting astride a mound of hazelnuts. Its fur blazes a bright russet color, its tail fanned out like a sail. I glance up, and in the neighboring pine tree I see two or three more, racing up and down the trunk, pausing every so often to steal a glance at the feast below, waiting their turn. These are red squirrels, and to see them in the wild, let alone in such numbers, is a rare treat. The animals were once common throughout the United Kingdom, but the invasive gray squirrel has pushed them to the brink of extinction in all but a few strongholds. When American novelist Kurt Vonnegut addressed the Bennington College class of 1970—1 year after publishing his best-selling novel, Slaughterhouse-Five—he hit the crowd with his signature one-two punch. “I fully expected that by the time I was 21, some scientist … would have taken a color photograph of God Almighty and sold it to Popular Mechanics magazine,” he said. “What actually happened … was that we dropped scientific truth on Hiroshima.” This weary skepticism for the scientific endeavor rings through many of Vonnegut’s 14 novels and dozens of short stories. For what would have been the famed author’s 100th birthday, Science talked to literary scholars, philosophers of science, and political theorists about the messages Vonnegut left for the scientific community—and why he’s more relevant than ever.

When American novelist Kurt Vonnegut addressed the Bennington College class of 1970—1 year after publishing his best-selling novel, Slaughterhouse-Five—he hit the crowd with his signature one-two punch. “I fully expected that by the time I was 21, some scientist … would have taken a color photograph of God Almighty and sold it to Popular Mechanics magazine,” he said. “What actually happened … was that we dropped scientific truth on Hiroshima.” This weary skepticism for the scientific endeavor rings through many of Vonnegut’s 14 novels and dozens of short stories. For what would have been the famed author’s 100th birthday, Science talked to literary scholars, philosophers of science, and political theorists about the messages Vonnegut left for the scientific community—and why he’s more relevant than ever. Francis Fukuyama’s work is generally treated much the way pigeons treat statues: as something on which to deposit badly digested ideas, which are then left for others to clean up. His notoriety for the “End of History” thesis is based on a misreading of that phrase, not a real reading of his 1989 National Interest article “The End of History?” or his less sanguine 1992 book The End of History and the Last Man. His subsequent work has received respectful public attention, but little scholarly engagement; he is treated more as a symptom than an intellect. Even with this book, the pattern of neglect-by-vague-praise continues: None of its many reviewers, for all their pretense at comprehension, noticed that his drive-by definition of “deontology” (“not linked to any ontology or substantive theory of human nature”) is totally wrong: Deontology comes from deon, a Greek word here meaning something like “duty” and refers to the study of ethics.

Francis Fukuyama’s work is generally treated much the way pigeons treat statues: as something on which to deposit badly digested ideas, which are then left for others to clean up. His notoriety for the “End of History” thesis is based on a misreading of that phrase, not a real reading of his 1989 National Interest article “The End of History?” or his less sanguine 1992 book The End of History and the Last Man. His subsequent work has received respectful public attention, but little scholarly engagement; he is treated more as a symptom than an intellect. Even with this book, the pattern of neglect-by-vague-praise continues: None of its many reviewers, for all their pretense at comprehension, noticed that his drive-by definition of “deontology” (“not linked to any ontology or substantive theory of human nature”) is totally wrong: Deontology comes from deon, a Greek word here meaning something like “duty” and refers to the study of ethics.