Harmony Holiday at Bookforum:

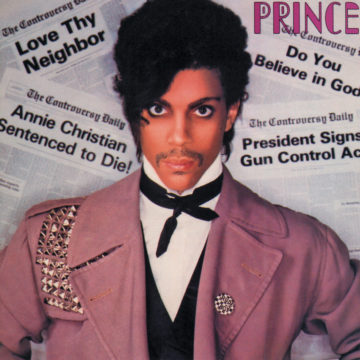

PINUPS ARE RUMORED TO EMERGE FROM THE SEA, mer-peoples caught between nautical and earthly existence, so that maybe there are fewer black pinups circulating in popular culture, because the sea for us is in part the graveyard of the Middle Passage, not just an escapist fantasy. Black pinups would emerge blood-drenched and haunting, rather than seducing onlookers. Just bypass the trance of glamour and observe Josephine Baker’s double consciousness in any photograph, at once entertaining you and devastating you, silly and caustic with grief. Or just look at Prince and try not to fall in love. Hilton Als’s account of witnessing, meeting, interviewing, befriending, and loving Prince Rogers Nelson begins with the recapitulation of a Jamie Foxx stand-up bit, in which Foxx describes involuntarily lusting after Prince at first glance, I mean he’s cute, he’s pretty. Foxx sits with the ambiguity onstage, seeming to need the confessional; it’s the frantic announcement of a romance that’s been a secret for too long. He’s not just aroused when he looks into and avoids Prince’s eyes during their conversation, he’s overcome and forever changed. Prince is loved, lusted after, and objectified like a pinup because his presence and his music compel us to overcome ourselves. His is the kind of irreducible androgyny that upends gender without the use of any jargon—it’s God-driven wish-fulfillment.

PINUPS ARE RUMORED TO EMERGE FROM THE SEA, mer-peoples caught between nautical and earthly existence, so that maybe there are fewer black pinups circulating in popular culture, because the sea for us is in part the graveyard of the Middle Passage, not just an escapist fantasy. Black pinups would emerge blood-drenched and haunting, rather than seducing onlookers. Just bypass the trance of glamour and observe Josephine Baker’s double consciousness in any photograph, at once entertaining you and devastating you, silly and caustic with grief. Or just look at Prince and try not to fall in love. Hilton Als’s account of witnessing, meeting, interviewing, befriending, and loving Prince Rogers Nelson begins with the recapitulation of a Jamie Foxx stand-up bit, in which Foxx describes involuntarily lusting after Prince at first glance, I mean he’s cute, he’s pretty. Foxx sits with the ambiguity onstage, seeming to need the confessional; it’s the frantic announcement of a romance that’s been a secret for too long. He’s not just aroused when he looks into and avoids Prince’s eyes during their conversation, he’s overcome and forever changed. Prince is loved, lusted after, and objectified like a pinup because his presence and his music compel us to overcome ourselves. His is the kind of irreducible androgyny that upends gender without the use of any jargon—it’s God-driven wish-fulfillment.

more here.

O

O When the Italian writer and publisher Roberto Calasso died last year, he was more widely admired than understood. When he is praised in the Anglophone world, it is usually for being erudite. Meanwhile, in his native Italy, Calasso is better known as a publishing impresario, because of his leadership of the independent publishing house Adelphi. Calasso’s great work, a capacious 11-part series that he began in 1983 with The Ruin of Kasch, and ended in 2021 with The Tablet of Destinies, is often said to be indescribable. Actually, it is rather straightforward once you have the key. Calasso is writing gnoseology (a word he uses often)—that is, an examination and history of esoteric knowledge.

When the Italian writer and publisher Roberto Calasso died last year, he was more widely admired than understood. When he is praised in the Anglophone world, it is usually for being erudite. Meanwhile, in his native Italy, Calasso is better known as a publishing impresario, because of his leadership of the independent publishing house Adelphi. Calasso’s great work, a capacious 11-part series that he began in 1983 with The Ruin of Kasch, and ended in 2021 with The Tablet of Destinies, is often said to be indescribable. Actually, it is rather straightforward once you have the key. Calasso is writing gnoseology (a word he uses often)—that is, an examination and history of esoteric knowledge. Decades of work and billions of dollars went into funding clinical trials of dozens of drug compounds that targeted amyloid plaques. Yet almost none of the trials showed meaningful benefits to patients with the disease.

Decades of work and billions of dollars went into funding clinical trials of dozens of drug compounds that targeted amyloid plaques. Yet almost none of the trials showed meaningful benefits to patients with the disease. For the past 12 weeks, revolutionary sentiment has been coursing through the cities and towns of the Persian plateau. The agitation was triggered by the

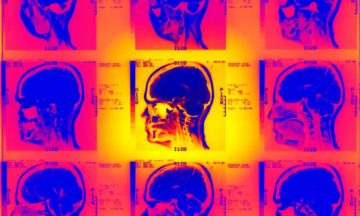

For the past 12 weeks, revolutionary sentiment has been coursing through the cities and towns of the Persian plateau. The agitation was triggered by the  Bell’s palsy is a neurological condition resulting from damage to the seventh cranial nerve, and typified by partial facial paralysis and pain on one side of the head.

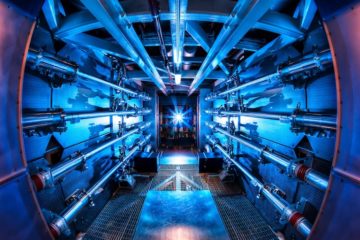

Bell’s palsy is a neurological condition resulting from damage to the seventh cranial nerve, and typified by partial facial paralysis and pain on one side of the head. Existing nuclear power plants work through fission — splitting apart heavy atoms to create energy. In fission, a neutron collides with a heavy uranium atom, splitting it into lighter atoms and releasing a lot of heat and energy at the same time. Fusion, on the other hand, works in the opposite way — it involves smushing two atoms (often two hydrogen atoms) together to create a new element (often helium), in the same way that stars creates energy. In that process, the two hydrogen atoms lose a small amount of mass, which is converted to energy according to Einstein’s famous equation, E=mc². Because the speed of light is very, very fast — 300,000,000 meters per second — even a tiny amount of mass lost can result in a ton of energy.

Existing nuclear power plants work through fission — splitting apart heavy atoms to create energy. In fission, a neutron collides with a heavy uranium atom, splitting it into lighter atoms and releasing a lot of heat and energy at the same time. Fusion, on the other hand, works in the opposite way — it involves smushing two atoms (often two hydrogen atoms) together to create a new element (often helium), in the same way that stars creates energy. In that process, the two hydrogen atoms lose a small amount of mass, which is converted to energy according to Einstein’s famous equation, E=mc². Because the speed of light is very, very fast — 300,000,000 meters per second — even a tiny amount of mass lost can result in a ton of energy.

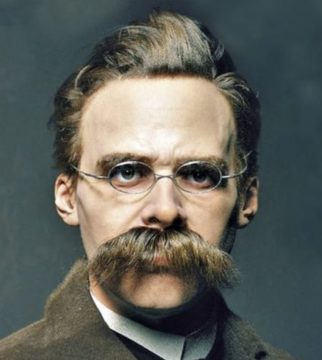

Should one be altruistic and act for the sake of others, even at a cost to oneself? Should one’s actions be free of any egoistic motivations? Is selflessness a virtue one ought to strive for and cultivate? To many of us the answer to such questions is so self-evident that even raising them would appear to be either a sign of moral obtuseness or an infantile attempt at provocation. For Friedrich Nietzsche, the 19th Century “immoralist” German philosopher, however, the answer to these questions was by no means straightforward and unequivocal. Rather, he believed that altruism and selflessness are neither virtues to be unconditionally pursued and celebrated nor obligations grounded in absolute morality. Moreover, he thought that other-regard (regard for others) is something to be practiced, if at all, with care and moderation; indeed, in some cases selflessness could pose a great danger or even be a sign of deep existential malaise.

Should one be altruistic and act for the sake of others, even at a cost to oneself? Should one’s actions be free of any egoistic motivations? Is selflessness a virtue one ought to strive for and cultivate? To many of us the answer to such questions is so self-evident that even raising them would appear to be either a sign of moral obtuseness or an infantile attempt at provocation. For Friedrich Nietzsche, the 19th Century “immoralist” German philosopher, however, the answer to these questions was by no means straightforward and unequivocal. Rather, he believed that altruism and selflessness are neither virtues to be unconditionally pursued and celebrated nor obligations grounded in absolute morality. Moreover, he thought that other-regard (regard for others) is something to be practiced, if at all, with care and moderation; indeed, in some cases selflessness could pose a great danger or even be a sign of deep existential malaise.

This century has not been kind to human-rights optimists, with 2022 being no exception. Many gains in the recognition and protection of the universal rights recognized in the post-World War II and post-Cold War years have stalled or been eroded. Russia’s criminal behavior in Ukraine is but the most recent example of a broader trend – made even more shocking by Russia’s status as a permanent member of the United Nations Security Council, which exists to uphold the very principles of international law that the Kremlin is now so brazenly violating.

This century has not been kind to human-rights optimists, with 2022 being no exception. Many gains in the recognition and protection of the universal rights recognized in the post-World War II and post-Cold War years have stalled or been eroded. Russia’s criminal behavior in Ukraine is but the most recent example of a broader trend – made even more shocking by Russia’s status as a permanent member of the United Nations Security Council, which exists to uphold the very principles of international law that the Kremlin is now so brazenly violating. My everyday experiences as a chemistry professor at an American university in 2021 bring back memories from my school and university time in the USSR. Not good memories—more like Orwellian nightmares. I will compare my past and present experiences to illustrate the following parallels between the USSR and the US today: (i) the atmosphere of fear and self-censorship; (ii) the omnipresence of ideology (focusing on examples from science); (iii) an intolerance of dissenting opinions (i.e., suppression of ideas and people, censorship, and Newspeak); (iv) the use of social engineering to solve real and imagined problems.

My everyday experiences as a chemistry professor at an American university in 2021 bring back memories from my school and university time in the USSR. Not good memories—more like Orwellian nightmares. I will compare my past and present experiences to illustrate the following parallels between the USSR and the US today: (i) the atmosphere of fear and self-censorship; (ii) the omnipresence of ideology (focusing on examples from science); (iii) an intolerance of dissenting opinions (i.e., suppression of ideas and people, censorship, and Newspeak); (iv) the use of social engineering to solve real and imagined problems. Moheb Costandi’s title is taken from Nietzsche’s philosophical masterpiece Thus Spoke Zarathustra: “The awakened and knowing say: body am I entirely, and nothing more; and soul is only the name for something about the body.” The radical rejection of mind-body dualism expressed in this sentence is shared today by most neuroscientists, who believe that the mind is a product of the brain. Indeed, this “neurocentric” view has been widely accepted and, writes Costandi, “the idea that we are our brains is now firmly established”.

Moheb Costandi’s title is taken from Nietzsche’s philosophical masterpiece Thus Spoke Zarathustra: “The awakened and knowing say: body am I entirely, and nothing more; and soul is only the name for something about the body.” The radical rejection of mind-body dualism expressed in this sentence is shared today by most neuroscientists, who believe that the mind is a product of the brain. Indeed, this “neurocentric” view has been widely accepted and, writes Costandi, “the idea that we are our brains is now firmly established”.