Category: Recommended Reading

Molly Ringwald And Godard

Molly Ringwald at The New Yorker:

Before we started filming, I asked someone from the production team when I would meet makeup, hair, and wardrobe, and was told that I would be doing my own. I was also informed that Godard would be stopping by my room to choose Cordelia’s costumes from the clothes I had brought with me. It was the first I’d heard of this, and I suddenly wished I had been more selective in my packing. I went back to my room, picked out a nice sweater and skirt, tied a scarf in my hair, and carefully applied my makeup. Then I wrote postcards while I waited for Godard, the contents of my suitcase neatly arranged on the bed. When I greeted him and an assistant at the door, he took one look at my face and exclaimed, “No, no, no! Too much makeup! Take it off. If you must, just a little mascara, that’s all.” The “a” in “all” was pronounced as an “o,” articulated in the exact same way he later asked me to pronounce Cordelia’s answer to her father’s question about what she will say to prove her love for him. “Not no‑thing.” no thing. He split the word in two, and I could tell that this distinction was important to him, without really understanding why.

Before we started filming, I asked someone from the production team when I would meet makeup, hair, and wardrobe, and was told that I would be doing my own. I was also informed that Godard would be stopping by my room to choose Cordelia’s costumes from the clothes I had brought with me. It was the first I’d heard of this, and I suddenly wished I had been more selective in my packing. I went back to my room, picked out a nice sweater and skirt, tied a scarf in my hair, and carefully applied my makeup. Then I wrote postcards while I waited for Godard, the contents of my suitcase neatly arranged on the bed. When I greeted him and an assistant at the door, he took one look at my face and exclaimed, “No, no, no! Too much makeup! Take it off. If you must, just a little mascara, that’s all.” The “a” in “all” was pronounced as an “o,” articulated in the exact same way he later asked me to pronounce Cordelia’s answer to her father’s question about what she will say to prove her love for him. “Not no‑thing.” no thing. He split the word in two, and I could tell that this distinction was important to him, without really understanding why.

more here.

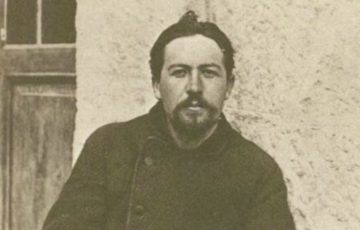

How Chekhov Made Sense of His Surroundings Through Writing Short Stories

Bob Blaisdell in Literary Hub:

Anton Chekhov’s biography in 1886-1887 is captured almost completely in the writing that he was doing. Reading the stories, we are as close as we can be to being in his company.

Anton Chekhov’s biography in 1886-1887 is captured almost completely in the writing that he was doing. Reading the stories, we are as close as we can be to being in his company.

In 1886, the twenty-six-year-old Moscow doctor published 112 short stories, humor pieces, and articles. In 1887, he published sixty-four short stories. The young author was, to his surprise and occasional embarrassment, famous; admired by, among others, Russia’s literary giants Lev Tolstoy and Nikolay Leskov. In these two years, three volumes of his short stories were published.

Meanwhile, three hours a day, six days a week, Dr. Chekhov treated patients in his office at his family’s residence, and also made house calls; he lived with and supported his parents and younger siblings.

More here.

Your gut bacteria may influence how motivated you are to exercise

Grace Wade in New Scientist:

Motivation to exercise may come from the gut in addition to the brain. A study in mice finds that certain gut bacteria can increase the release of dopamine during physical activity, which helps drive motivation.

Motivation to exercise may come from the gut in addition to the brain. A study in mice finds that certain gut bacteria can increase the release of dopamine during physical activity, which helps drive motivation.

Though most of us know that exercise comes with many benefits, how much people exercise varies widely, says Christoph Thaiss at the University of Pennsylvania. He and his colleagues wanted to identify physiological factors that may explain this variation.

They collected data from 106 mice on exercise capacity, genetics, gut microbiome composition and more, and fed it to a machine learning model for analysis. The model found that how often mice exercised was most strongly associated with the makeup of their microbiome.

More here.

The “Twitter Files” Show It’s Time to Reimagine Free Speech Online

David French in Persuasion:

A few years ago I was invited to an off-the-record meeting with senior executives at a major social media company. The topic was free speech. I’d just written a piece for the New York Times called “A better way to ban Alex Jones.” My position was simple: If social media companies want to create a true marketplace of ideas, they should look to the First Amendment to guide their policies.

A few years ago I was invited to an off-the-record meeting with senior executives at a major social media company. The topic was free speech. I’d just written a piece for the New York Times called “A better way to ban Alex Jones.” My position was simple: If social media companies want to create a true marketplace of ideas, they should look to the First Amendment to guide their policies.

This position wasn’t adopted on a whim, but because I’d spent decades watching powerful private institutions struggle—and fail—to create free speech regulations that purported to permit open debate at the same time that they suppressed allegedly hateful or harmful speech. As I told the tech executives, “You’re trying to recreate the college speech code, except online, and it’s not going to work.”

I’ve been thinking about that conversation ever since Elon Musk took over Twitter, and particularly since Matt Taibbi and Bari Weiss last week began releasing selected internal Twitter files at Musk’s behest.

More here.

Love at First Sight: John Hurt stars in this Oscar short-listed short film

Thursday Poem

Like You

Like you I

love love, life, the sweet smell

of things, the sky-blue

landscape of January days.

And my blood boils up

and I laugh through eyes

that have known the buds of tears.

I believe the world is beautiful

and that poetry, like bread, is for everyone.

And that my veins don’t end in me

but in the unanimous blood

of those who struggle for life,

love,

little things,

landscape and bread,

the poetry of everyone.

by Roque Dalton

from Poetry Like Bread

Curbstone Press, 1997

Original Spanish @ Read More below

Psychedelic startups are betting on synthetic versions of “magic” mushrooms

Troy Farah in Salon:

It seems as though “magic” mushrooms containing the psychedelic drug psilocybin are suddenly in vogue, judging by the sudden pop up of shroom dispensaries across North America and the fact that Colorado recently joined Oregon, Connecticut and Maryland in legalizing psychedelic therapy (though no clinics have opened yet) — plus the upward trend in “microdosing” hallucinogens, a new Netflix series, and on and on.

It seems as though “magic” mushrooms containing the psychedelic drug psilocybin are suddenly in vogue, judging by the sudden pop up of shroom dispensaries across North America and the fact that Colorado recently joined Oregon, Connecticut and Maryland in legalizing psychedelic therapy (though no clinics have opened yet) — plus the upward trend in “microdosing” hallucinogens, a new Netflix series, and on and on.

But humans have been consuming these fungi for thousands of years, and some theories suggesting our ancestors even ate them millions of years ago. Ancient humans probably consumed these psychoactive mushrooms for good reason: in some people, psilocybin seems to stir creativity, spiritual connectedness and alleviate mental health pitfalls like depression and anxiety.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration clearly sees potential in psilocybin. They’ve awarded the drug “Breakthrough Therapy” status for depressive disorders not once, but twice — first for Compass Pathways in 2018 and a second time with Usona Institute in 2019. This label helps the drugs move more quickly through the pharmaceutical approval process, though it doesn’t always equal success. The latest estimate is that psilocybin will become an FDA-approved drug before 2026, but there’s no guarantee this will happen. In the meantime, psilocybin remains highly illegal at the federal level.

More here.

From Bowling Alone to Posting Alone

Anton Jager in Jacobin:

Last year, the Survey Center on American Life published a study tracking friendship patterns in the United States. The report was anything but heartening. Registering a “friendship recession,” the report noted how Americans were increasingly lonely and isolated: 12 percent of them now say they do not have close friendships, compared to 3 percent in 1990, and almost 50 percent said they lost contact with friends during the COVID-19 pandemic. The psychosomatic fallout was dire: heart disease, sleep disruptions, increased risk of Alzheimer’s. The friendship recession has had potentially lethal effects.

Last year, the Survey Center on American Life published a study tracking friendship patterns in the United States. The report was anything but heartening. Registering a “friendship recession,” the report noted how Americans were increasingly lonely and isolated: 12 percent of them now say they do not have close friendships, compared to 3 percent in 1990, and almost 50 percent said they lost contact with friends during the COVID-19 pandemic. The psychosomatic fallout was dire: heart disease, sleep disruptions, increased risk of Alzheimer’s. The friendship recession has had potentially lethal effects.

The center’s study offered a miniaturized model of a much broader process that has overtaken countries beyond the United States in the last thirty years. As the quintessential voluntary association, friendship circles stand in for other institutions in our collective life — unions, parties, clubs. In his memoirs, French philosopher Jean-Claude Michéa said that one of the most disconcerting moments of his childhood was the day he discovered that there were people in the village who were not members of the Communist Party. “That seemed unimaginable,” he recalled, as if those people “lived outside of society.” Not coincidentally, in May 1968, French students sometimes compared the relationship of workers to the Communist Party with that of Christians to the church. The Christians yearned for God, and the workers for revolution. Instead, “the Christians got the church, and the working class got the party.”

More here.

Wednesday, December 14, 2022

Rulers in Times of Transition

The Sprawling Pan-Asian Crime Ring Of Silicon Valley

Natalie So at The Believer:

In the early ’90s, the FBI had learned of a Vietnamese-Chinese heroin organization that was closely aligned with Vietnamese street gangs throughout the United States. Their connections were wide-ranging, and they were loosely affiliated with the Triads (including Frank Ma, one of the last Chinese “godfathers” in New York), as well as with several other high-echelon Asian crime bosses in various American cities. But this heroin organization operated differently from the Asian gangs of previous generations.

In the early ’90s, the FBI had learned of a Vietnamese-Chinese heroin organization that was closely aligned with Vietnamese street gangs throughout the United States. Their connections were wide-ranging, and they were loosely affiliated with the Triads (including Frank Ma, one of the last Chinese “godfathers” in New York), as well as with several other high-echelon Asian crime bosses in various American cities. But this heroin organization operated differently from the Asian gangs of previous generations.

First, they relied on two key pieces of technology: the cellular phone and the pager. They were financially and technologically savvy, and instead of being tied to one specific location, they operated a national network, with cells and confederates in various cities.

more here.

Rereading Ernst Jünger

Jessi Jezewska Stevens at The Paris Review:

Jünger’s politics were complicated, if not incoherent. A decorated veteran of the First World War (he made his literary debut with a bellicose, best-selling diary from the trenches, Storm of Steel) who was praised by Hitler but who refused to join the Nazi Party; a self-taught conservative intellectual (Jünger never completed university) who won the admiration of Marxist writers like Bertolt Brecht; an incurable elitist sympathetic to communist centralization (he opposed liberalism above all)—the Weimar-era Jünger projected an aloof, aestheticizing, and ultimately paradoxical strain of fascism. Kracauer captured what feels most damning about Jünger’s political thinking during this time in a review of his controversial treatise The Worker (1932) for the Frankfurter Zeitung, in which he accused Jünger of having “metaphysicized” (metaphysiziert) politics: What about real, tangible action in our own historical moment? Metaphysics is an escape.

Jünger’s politics were complicated, if not incoherent. A decorated veteran of the First World War (he made his literary debut with a bellicose, best-selling diary from the trenches, Storm of Steel) who was praised by Hitler but who refused to join the Nazi Party; a self-taught conservative intellectual (Jünger never completed university) who won the admiration of Marxist writers like Bertolt Brecht; an incurable elitist sympathetic to communist centralization (he opposed liberalism above all)—the Weimar-era Jünger projected an aloof, aestheticizing, and ultimately paradoxical strain of fascism. Kracauer captured what feels most damning about Jünger’s political thinking during this time in a review of his controversial treatise The Worker (1932) for the Frankfurter Zeitung, in which he accused Jünger of having “metaphysicized” (metaphysiziert) politics: What about real, tangible action in our own historical moment? Metaphysics is an escape.

These ideological contradictions—or is it political ambivalence?—extended throughout the Second World War. The tendency to view the world through the metaphysical lens of cycles of power as opposed to “right and left” certainly seems to have granted Jünger, then an influential conservative voice, a great deal of moral latitude in distancing himself from the horrors emerging around him.

more here.

Reflecting on three monumental works of modernism—James Joyce’s Ulysses, T. S. Eliot’s The Waste Land, and Ludwig Wittgenstein’s Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus—a hundred years on

Johanna Winant in the Boston Review:

This year marks the centenary of modernism’s annus mirabilis. For many, that means T. S. Eliot’s The Waste Land and James Joyce’s Ulysses—both first published in book form in 1922—perhaps along with the first English language translation of Ludwig Wittgenstein’s Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus. These books are in different genres and disciplines—poetry, fiction, philosophy—but all of them wed experimental literary aesthetics with highly abstract intellectual projects. All invoke myths to represent immense aesthetic and intellectual challenges: each tells of an arduous journey, that could, if successful, be redemptive, even transformative. Each text has its hero, but in each case the hero is also—or really—you. You, the reader, are challenged to find your way through these depths and heights and broad, rough seas. The journey is perilous, filled with traps as well as marvels. Should you succeed, your home may look different by the end; you will be changed too.

This year marks the centenary of modernism’s annus mirabilis. For many, that means T. S. Eliot’s The Waste Land and James Joyce’s Ulysses—both first published in book form in 1922—perhaps along with the first English language translation of Ludwig Wittgenstein’s Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus. These books are in different genres and disciplines—poetry, fiction, philosophy—but all of them wed experimental literary aesthetics with highly abstract intellectual projects. All invoke myths to represent immense aesthetic and intellectual challenges: each tells of an arduous journey, that could, if successful, be redemptive, even transformative. Each text has its hero, but in each case the hero is also—or really—you. You, the reader, are challenged to find your way through these depths and heights and broad, rough seas. The journey is perilous, filled with traps as well as marvels. Should you succeed, your home may look different by the end; you will be changed too.

This account of these three notoriously difficult and undeniably monumental books is true, but it is also a product of a century of hype.

More here.

Sean Carroll’s Mindscape Podcast: Lara Buchak on Risk and Rationality

Sean Carroll in Preposterous Universe:

Life is rich with moments of uncertainty, where we’re not exactly sure what’s going to happen next. We often find ourselves in situations where we have to choose between different kinds of uncertainty; maybe one option is very likely to have a “pretty good” outcome, while another has some probability for “great” and some for “truly awful.” In such circumstances, what’s the rational way to choose? Is it rational to go to great lengths to avoid choices where the worst outcome is very bad? Lara Buchak argues that it is, thereby expanding and generalizing the usual rules of rational choice in conditions of risk.

Life is rich with moments of uncertainty, where we’re not exactly sure what’s going to happen next. We often find ourselves in situations where we have to choose between different kinds of uncertainty; maybe one option is very likely to have a “pretty good” outcome, while another has some probability for “great” and some for “truly awful.” In such circumstances, what’s the rational way to choose? Is it rational to go to great lengths to avoid choices where the worst outcome is very bad? Lara Buchak argues that it is, thereby expanding and generalizing the usual rules of rational choice in conditions of risk.

More here.

Statistics are not always what they seem

Christopher J. Snowdon in Quillette:

H.G. Wells once predicted that “statistical thinking will one day be as necessary for efficient citizenship as the ability to read and write.” It was a slight exaggeration, but in an age of big data in which governments pride themselves on being “evidence-based” and “guided by the science,” an understanding of where facts and figures come from is important if you want to think clearly.

H.G. Wells once predicted that “statistical thinking will one day be as necessary for efficient citizenship as the ability to read and write.” It was a slight exaggeration, but in an age of big data in which governments pride themselves on being “evidence-based” and “guided by the science,” an understanding of where facts and figures come from is important if you want to think clearly.

Georgina Sturge works in the House of Commons Library where she furnishes UK MPs with statistics. If Bad Data is any guide, she also provides them with caveats and other words of caution, which are ignored. This informative, reasoned, and apolitical book offers a string of examples to show that statistics are not always what they seem. Some statistics are rigged for political reasons. Others are inherently flawed. Some are close to guesswork. Even crucial variables such as Gross National Income and life expectancy are shrouded in more uncertainty than you might think. We don’t really know how many people live in Britain legally, let alone illegally. The number of people who are living in poverty varies enormously depending on how you measure it.

More here.

Sabine Hossenfelder: What’s the Deep Meaning of Probability?

Wednesday Poem

The Buddy Holly Poem

It’s so easy

when you realize

that all the squirrels

on the shingled rooftops

of Milwaukee

are Buddha

that all trees shake green

in the wind

that the moon is you

Sing

that the whole of every note

is individual and one

that love is free

every day

on the blue earth

Listen to me

by Maurice Kilwein Guvara

from Touching the Fire

Anchor Books, 1998

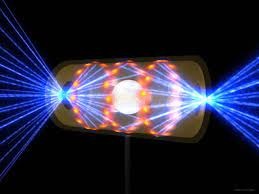

The Fusion Breakthrough Suggests That Maybe Someday We’ll Have a Second Sun

Bill McKibben in The New Yorker:

On Tuesday, the Department of Energy is expected to announce a breakthrough in fusion energy: according to early reports, scientists at the government’s Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, in California, have succeeded for the first time in making their complex and expensive machinery produce more power than it uses, if only for an instant. It’s a breakthrough of great significance—in essence, the researchers are learning to build a second sun. And it was greeted with the requisite hosannas—the Washington Post described it as a “holy grail,” a “major milestone in the decades-long, multibillion-dollar quest to develop a technology that provides unlimited, cheap, clean power.”

On Tuesday, the Department of Energy is expected to announce a breakthrough in fusion energy: according to early reports, scientists at the government’s Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, in California, have succeeded for the first time in making their complex and expensive machinery produce more power than it uses, if only for an instant. It’s a breakthrough of great significance—in essence, the researchers are learning to build a second sun. And it was greeted with the requisite hosannas—the Washington Post described it as a “holy grail,” a “major milestone in the decades-long, multibillion-dollar quest to develop a technology that provides unlimited, cheap, clean power.”

That it comes with equally requisite caveats does not diminish the glory of the achievement, but they’re important, too. As a fusion expert at the University of Cambridge, in England, told CNN on Monday, “This result is miles away from actual energy gain required for the production of electricity. Therefore, we can say (it) is a success of the science but a long way from providing useful energy.” Among other things, producing this reaction required one of the largest lasers in the world, and the reaction creates neutrons that can destroy the very equipment required to produce it. As the Post put it, “Building devices that are large enough to create fusion power at scale” would “require materials that are extraordinarily difficult to produce.” It is therefore still “at least a decade—maybe decades—away from commercial use.”

More here.

Ketamine Flips a “Switch” in Mice’s Brain Circuitry

Andy Carstens in The Scientist:

In the 1950s, scientists on a mission to create better anesthesia drugs synthesized phencyclidine, commonly known as PCP. Though PCP worked well to keep most people unconscious during surgical procedures, some experienced what the authors of a 1959 trial described as “delirium and hallucinations which, although usually of a highly pleasurable nature, are sometimes rather terrifying to the patients.” This so-called dissociated state—when what the brain experiences is disconnected from reality—lasted as long as 12 hours.

In the 1950s, scientists on a mission to create better anesthesia drugs synthesized phencyclidine, commonly known as PCP. Though PCP worked well to keep most people unconscious during surgical procedures, some experienced what the authors of a 1959 trial described as “delirium and hallucinations which, although usually of a highly pleasurable nature, are sometimes rather terrifying to the patients.” This so-called dissociated state—when what the brain experiences is disconnected from reality—lasted as long as 12 hours.

Seeking a shorter-acting agent, researchers in the 1960s made a compound that’s structurally related to PCP called ketamine. Ketamine remains a common anesthetic today, says Joe Cichon, a neuroscientist and anesthesiologist at the University of Pennsylvania’s Perelman School of Medicine. At lower doses than would be used for anesthesia, people remain conscious yet experience a similar dissociated state as with PCP but for far less time. In the 2000s, researchers found that these lower, so-called subhypnotic doses of ketamine have an antidepressant effect that can last for several weeks, well after the body has metabolized the drug, Cichon says. “And still to this day, after 60 years of being available for human use . . . we still don’t quite understand how it exerts all these different effects over a wide range of doses—that’s the mystery of ketamine.”

Now, Cichon and his colleagues have uncovered a new clue: By using calcium photon imaging, they found that the drug flips a “switch” in mice brains, shutting off neurons that had been firing in the awake state while activating a separate group of previously dormant neurons.

More here.

Tuesday, December 13, 2022

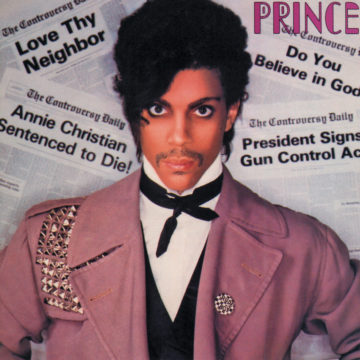

Hilton Als’s Conflicted Love Letter To Prince

Harmony Holiday at Bookforum:

PINUPS ARE RUMORED TO EMERGE FROM THE SEA, mer-peoples caught between nautical and earthly existence, so that maybe there are fewer black pinups circulating in popular culture, because the sea for us is in part the graveyard of the Middle Passage, not just an escapist fantasy. Black pinups would emerge blood-drenched and haunting, rather than seducing onlookers. Just bypass the trance of glamour and observe Josephine Baker’s double consciousness in any photograph, at once entertaining you and devastating you, silly and caustic with grief. Or just look at Prince and try not to fall in love. Hilton Als’s account of witnessing, meeting, interviewing, befriending, and loving Prince Rogers Nelson begins with the recapitulation of a Jamie Foxx stand-up bit, in which Foxx describes involuntarily lusting after Prince at first glance, I mean he’s cute, he’s pretty. Foxx sits with the ambiguity onstage, seeming to need the confessional; it’s the frantic announcement of a romance that’s been a secret for too long. He’s not just aroused when he looks into and avoids Prince’s eyes during their conversation, he’s overcome and forever changed. Prince is loved, lusted after, and objectified like a pinup because his presence and his music compel us to overcome ourselves. His is the kind of irreducible androgyny that upends gender without the use of any jargon—it’s God-driven wish-fulfillment.

PINUPS ARE RUMORED TO EMERGE FROM THE SEA, mer-peoples caught between nautical and earthly existence, so that maybe there are fewer black pinups circulating in popular culture, because the sea for us is in part the graveyard of the Middle Passage, not just an escapist fantasy. Black pinups would emerge blood-drenched and haunting, rather than seducing onlookers. Just bypass the trance of glamour and observe Josephine Baker’s double consciousness in any photograph, at once entertaining you and devastating you, silly and caustic with grief. Or just look at Prince and try not to fall in love. Hilton Als’s account of witnessing, meeting, interviewing, befriending, and loving Prince Rogers Nelson begins with the recapitulation of a Jamie Foxx stand-up bit, in which Foxx describes involuntarily lusting after Prince at first glance, I mean he’s cute, he’s pretty. Foxx sits with the ambiguity onstage, seeming to need the confessional; it’s the frantic announcement of a romance that’s been a secret for too long. He’s not just aroused when he looks into and avoids Prince’s eyes during their conversation, he’s overcome and forever changed. Prince is loved, lusted after, and objectified like a pinup because his presence and his music compel us to overcome ourselves. His is the kind of irreducible androgyny that upends gender without the use of any jargon—it’s God-driven wish-fulfillment.

more here.