Eida Edemariam in The Guardian:

One afternoon not long after the Obamas had moved into the White House, Michelle organised a playdate for her youngest daughter, Sasha. The children were at their new school and she was worried about how they were settling in. So, in a move recognisable to parents everywhere, she hovered unseen nearby, listening intently, “quietly overcome with emotion any time a new peal of laughter erupted from Sasha’s room”. When it was over she did, again, what any parent of a small child might do, and went out to meet the new friend’s mother. She wanted to chat about how the playdate had gone and maybe make a new friend for herself – at which point all relatability abruptly ended: a rustling surrounded her as her Secret Service detail, who hadn’t planned for this, talked urgently into their wrist microphones. The mother’s car was swiftly encircled by a Counter Assault Team. Hey there, Obama said. The woman, “eyeballing the guards clad in helmets and black battle dress … very, very slowly opened the car door and got out”.

One afternoon not long after the Obamas had moved into the White House, Michelle organised a playdate for her youngest daughter, Sasha. The children were at their new school and she was worried about how they were settling in. So, in a move recognisable to parents everywhere, she hovered unseen nearby, listening intently, “quietly overcome with emotion any time a new peal of laughter erupted from Sasha’s room”. When it was over she did, again, what any parent of a small child might do, and went out to meet the new friend’s mother. She wanted to chat about how the playdate had gone and maybe make a new friend for herself – at which point all relatability abruptly ended: a rustling surrounded her as her Secret Service detail, who hadn’t planned for this, talked urgently into their wrist microphones. The mother’s car was swiftly encircled by a Counter Assault Team. Hey there, Obama said. The woman, “eyeballing the guards clad in helmets and black battle dress … very, very slowly opened the car door and got out”.

It’s a funny anecdote. But like every story in The Light We Carry, and in Obama’s previous book, her memoir Becoming, it is told in the service of a serious point, which in this case is that making sustaining friendships requires effort and intention.

More here.

John P. Porcari is a bit of a reality TV show junkie. When he wants to work out, Dr. Porcari, a retired professor of sports and exercise science from the University of Wisconsin-LaCrosse, goes downstairs and watches “Alaska: The Last Frontier” or “Naked and Afraid” while bouncing on a mini trampoline. Just before speaking with The Times, he had completed four sets of 50 bounces while watching Discovery Channel’s “Gold Rush.” “I have a ski trip in January to get ready for,” he said.

John P. Porcari is a bit of a reality TV show junkie. When he wants to work out, Dr. Porcari, a retired professor of sports and exercise science from the University of Wisconsin-LaCrosse, goes downstairs and watches “Alaska: The Last Frontier” or “Naked and Afraid” while bouncing on a mini trampoline. Just before speaking with The Times, he had completed four sets of 50 bounces while watching Discovery Channel’s “Gold Rush.” “I have a ski trip in January to get ready for,” he said. Meis employed his dis- or un-layering style first in The Drunken Silenus: On Gods, Goats, and the Cracks in Reality.There Meis used Peter Paul Rubens’s 1620 painting, “The Drunken Silenus,” to expose the thinness of the membrane that separates mortality from immortality. Meis probes that membrane again in this second book, The Fate of the Animals. Here, he chooses Franz Marc’s 1913 painting, “The Fate of the Animals,” as a source for revealing or at least giving us a glimpse of the coming-into and going-out-of existence of all beings, including our own transient selves.

Meis employed his dis- or un-layering style first in The Drunken Silenus: On Gods, Goats, and the Cracks in Reality.There Meis used Peter Paul Rubens’s 1620 painting, “The Drunken Silenus,” to expose the thinness of the membrane that separates mortality from immortality. Meis probes that membrane again in this second book, The Fate of the Animals. Here, he chooses Franz Marc’s 1913 painting, “The Fate of the Animals,” as a source for revealing or at least giving us a glimpse of the coming-into and going-out-of existence of all beings, including our own transient selves. High school physics teachers describe them as featureless balls with one unit each of positive electric charge — the perfect foils for the negatively charged electrons that buzz around them. College students learn that the ball is actually a bundle of three elementary particles called quarks. But decades of research have revealed a deeper truth, one that’s too bizarre to fully capture with words or images.

High school physics teachers describe them as featureless balls with one unit each of positive electric charge — the perfect foils for the negatively charged electrons that buzz around them. College students learn that the ball is actually a bundle of three elementary particles called quarks. But decades of research have revealed a deeper truth, one that’s too bizarre to fully capture with words or images. I met Jerry when I was a pariah. I had repeatedly and publicly denounced the invasion of Iraq and, for my outspokenness, had been pushed out of The New York Times. I was receiving frequent death threats. My neighbors treated me as though I had leprosy. I had imploded my journalism career.

I met Jerry when I was a pariah. I had repeatedly and publicly denounced the invasion of Iraq and, for my outspokenness, had been pushed out of The New York Times. I was receiving frequent death threats. My neighbors treated me as though I had leprosy. I had imploded my journalism career. After they find dry ground for refuge, tie up surviving livestock, scan the ground for snakes and scorpions, queue, break queue and grab for food, plead for water, scream for tents, weep for loss, curse officials, lament fate — after all that, people whose lives have been upended by floods want to talk. I tell them I can’t do much. I am a researcher documenting and analyzing disaster impacts for various organizations, and it can be months before anyone even reads my reports. But sometimes, it’s enough for them to find someone who will listen.

After they find dry ground for refuge, tie up surviving livestock, scan the ground for snakes and scorpions, queue, break queue and grab for food, plead for water, scream for tents, weep for loss, curse officials, lament fate — after all that, people whose lives have been upended by floods want to talk. I tell them I can’t do much. I am a researcher documenting and analyzing disaster impacts for various organizations, and it can be months before anyone even reads my reports. But sometimes, it’s enough for them to find someone who will listen. Andrea Wulf’s substantial yet pacey new book concerns itself with a dazzling generation of German philosophers, scientists and poets who between the late 18th and early 19th centuries gathered in the provincial town of Jena and produced some of the most memorable works of European romanticism.

Andrea Wulf’s substantial yet pacey new book concerns itself with a dazzling generation of German philosophers, scientists and poets who between the late 18th and early 19th centuries gathered in the provincial town of Jena and produced some of the most memorable works of European romanticism. Judging by the titles of bills they propose, members of Congress occupy a space between used-car salesperson and poet. Over the past two years, lawmakers in the 117th Congress have introduced the

Judging by the titles of bills they propose, members of Congress occupy a space between used-car salesperson and poet. Over the past two years, lawmakers in the 117th Congress have introduced the  A

A Vergara’s newest book, Detroit Is No Dry Bones, powerfully documents the transformation of Detroit over the last several decades, offering an unflinching portrayal of a city gutted by decades of anti-urban public policies, intense racial segregation, and heartlessly mobile capital. Vergara’s approach is a reminder of the power of looking at small things—a fence, a broken window, a graffiti-strewn brick wall, a lawn ornament—to illustrate what might otherwise be impersonal processes and grand social forces. But Vergara’s keen eye also sees what cannot simply be reduced to urban decay. A raggedy lot becomes a lush garden, a blank wall becomes a canvas for an unknown artist, a pile of tires and a piece of wood become an impromptu bench at a bus stop. Vergara’s Detroit is not simply an acropolis, it is a place of rebirth and reinvention.

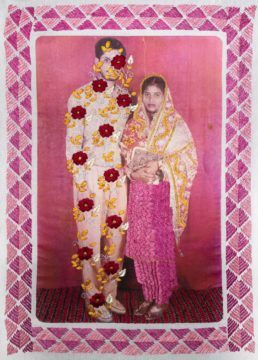

Vergara’s newest book, Detroit Is No Dry Bones, powerfully documents the transformation of Detroit over the last several decades, offering an unflinching portrayal of a city gutted by decades of anti-urban public policies, intense racial segregation, and heartlessly mobile capital. Vergara’s approach is a reminder of the power of looking at small things—a fence, a broken window, a graffiti-strewn brick wall, a lawn ornament—to illustrate what might otherwise be impersonal processes and grand social forces. But Vergara’s keen eye also sees what cannot simply be reduced to urban decay. A raggedy lot becomes a lush garden, a blank wall becomes a canvas for an unknown artist, a pile of tires and a piece of wood become an impromptu bench at a bus stop. Vergara’s Detroit is not simply an acropolis, it is a place of rebirth and reinvention. The images are printed on khadi, the cloth produced by traditional spinning wheels—the charkha, a device that is deeply rooted in Indian history. During the struggle for independence, Mahatma Gandhi used the spinning wheel as a symbol of self-reliance, urging Indians to spin their own cloth as a means of gaining economic freedom from the exploitation of British colonizers. If the spinning wheel has come to be a symbol of self-reliance, then in the work of Malik, the act of embroidery embodies resistance and the strength and care that can be found in community. Behind the work lies the reality of the struggle for women’s rights and the issue of gendered violence in India.

The images are printed on khadi, the cloth produced by traditional spinning wheels—the charkha, a device that is deeply rooted in Indian history. During the struggle for independence, Mahatma Gandhi used the spinning wheel as a symbol of self-reliance, urging Indians to spin their own cloth as a means of gaining economic freedom from the exploitation of British colonizers. If the spinning wheel has come to be a symbol of self-reliance, then in the work of Malik, the act of embroidery embodies resistance and the strength and care that can be found in community. Behind the work lies the reality of the struggle for women’s rights and the issue of gendered violence in India. In 1978, when

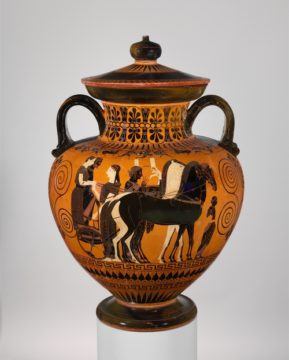

In 1978, when  There are distinct signs that the poet John Keats’ Grecian Urn has found its voice again. This is a surprise. The final Delphic utterance of the decorated vessel in his poem Ode to a Grecian Urn runs: “Beauty is Truth, Truth Beauty, — that is all / Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know.” Though well-known as verse, it has long been relegated to romantic wishful thinking.

There are distinct signs that the poet John Keats’ Grecian Urn has found its voice again. This is a surprise. The final Delphic utterance of the decorated vessel in his poem Ode to a Grecian Urn runs: “Beauty is Truth, Truth Beauty, — that is all / Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know.” Though well-known as verse, it has long been relegated to romantic wishful thinking. Artificial intelligence can learn and remember how to do multiple tasks by mimicking the way sleep helps us cement what we learned during waking hours.

Artificial intelligence can learn and remember how to do multiple tasks by mimicking the way sleep helps us cement what we learned during waking hours.