Keith Holyoak at The MIT Press Reader:

Artificial intelligence (AI) is in the process of changing the world and its societies in ways no one can fully predict. On the hazier side of the present horizon, there may come a tipping point at which AI surpasses the general intelligence of humans. (In various specific domains, notably mathematical calculation, the intersection point was passed decades ago.) Many people anticipate this technological moment, dubbed the Singularity, as a kind of Second Coming — though whether of a savior or of Yeats’s rough beast is less clear. Perhaps by constructing an artificial human, computer scientists will finally realize Mary Shelley’s vision.

Artificial intelligence (AI) is in the process of changing the world and its societies in ways no one can fully predict. On the hazier side of the present horizon, there may come a tipping point at which AI surpasses the general intelligence of humans. (In various specific domains, notably mathematical calculation, the intersection point was passed decades ago.) Many people anticipate this technological moment, dubbed the Singularity, as a kind of Second Coming — though whether of a savior or of Yeats’s rough beast is less clear. Perhaps by constructing an artificial human, computer scientists will finally realize Mary Shelley’s vision.

Of all the actual and potential consequences of AI, surely the least significant is that AI programs are beginning to write poetry. But that effort happens to be the AI application most relevant to our theme. And in a certain sense, poetry may serve as a kind of canary in the coal mine — an early indicator of the extent to which AI promises (threatens?) to challenge humans as artistic creators. If AI can be a poet, what other previously human-only roles will it slip into?

More here.

I was recently reading an old article by string theorist Robbert Dijkgraaf in Quanta Magazine entitled “

I was recently reading an old article by string theorist Robbert Dijkgraaf in Quanta Magazine entitled “ In the orthodox telling, there was only one revolution that mattered, after all. The fact that American revolutionaries won their independence in part because the French intervened in their British civil war has often been narrated as at most a useful irony. Certainly Africans or Natives had nothing to do with it, except as desperate fighters for their own marginal purposes: defined out of the story partly because they lost but mostly because, well, they were defined out of the story. Yet the century-long debate between “Progressive” (read: radical) versus “Whig” (liberal and conservative) historians about whether ordinary white people benefitted or whether elites did has begun to seem almost beside the point: there was more at stake for others than republicanism or nationhood.

In the orthodox telling, there was only one revolution that mattered, after all. The fact that American revolutionaries won their independence in part because the French intervened in their British civil war has often been narrated as at most a useful irony. Certainly Africans or Natives had nothing to do with it, except as desperate fighters for their own marginal purposes: defined out of the story partly because they lost but mostly because, well, they were defined out of the story. Yet the century-long debate between “Progressive” (read: radical) versus “Whig” (liberal and conservative) historians about whether ordinary white people benefitted or whether elites did has begun to seem almost beside the point: there was more at stake for others than republicanism or nationhood. The trip to

The trip to  The former Archbishop of Canterbury, Rowan Williams, recently selected Faith, Hope and Carnage as his New Statesman

The former Archbishop of Canterbury, Rowan Williams, recently selected Faith, Hope and Carnage as his New Statesman  The oldest DNA ever recovered has revealed a remarkable two-million-year-old ecosystem in Greenland, including the presence of an unlikely explorer: the mastodon.

The oldest DNA ever recovered has revealed a remarkable two-million-year-old ecosystem in Greenland, including the presence of an unlikely explorer: the mastodon. Why is april

Why is april

The medieval bubonic plague pandemic was a major historical event. But what happened next? To give myself some grounding on this topic, I previously reviewed

The medieval bubonic plague pandemic was a major historical event. But what happened next? To give myself some grounding on this topic, I previously reviewed  The Congressional decision to

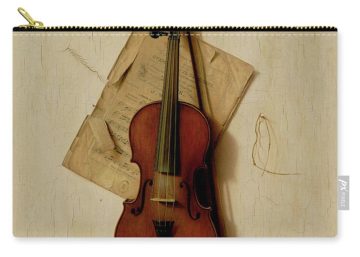

The Congressional decision to  As in magic, viewers of trompe l’oeil know they’re being deceived, and are in on the joke. And there may be something hard-wired in our attraction to those tricks. Gustav Kuhn, Reader in Psychology at Goldsmith’s, University of London, studies cognition and illusions, specifically in magic. No one really knows why we like to be tricked, he says, but he speculates that the attraction comes from “some sort of deep-rooted cognitive mechanism that encourages us to explore the unknown.” Studies of infants point in that direction. “Cognitive conflict is at the essence of magic,” he says. If you hide an object, then reveal the empty space where it was, “For really young infants, they don’t have a concept of object permanency, and so it doesn’t violate their assumptions about the world and they’re not really that interested. However, after the age of about two, where this violates their assumptions, they become captivated.”

As in magic, viewers of trompe l’oeil know they’re being deceived, and are in on the joke. And there may be something hard-wired in our attraction to those tricks. Gustav Kuhn, Reader in Psychology at Goldsmith’s, University of London, studies cognition and illusions, specifically in magic. No one really knows why we like to be tricked, he says, but he speculates that the attraction comes from “some sort of deep-rooted cognitive mechanism that encourages us to explore the unknown.” Studies of infants point in that direction. “Cognitive conflict is at the essence of magic,” he says. If you hide an object, then reveal the empty space where it was, “For really young infants, they don’t have a concept of object permanency, and so it doesn’t violate their assumptions about the world and they’re not really that interested. However, after the age of about two, where this violates their assumptions, they become captivated.” The end of history was not an idea that was original to Fukuyama; rather, as befits an age of ideological exhaustion, it was a vintage reissue harking back to an earlier era. The idea was hatched in the rubble of the Second World War and set the tone of intellectual life in the 1950s. Jacques Derrida once reminisced that it was the “daily bread” on which aspiring philosophers were raised back then. Its charismatic impresario was the Russian-born French philosopher Alexandre Kojève. Many others, however, came to terms with the idea the way one does with an ominous prognosis. For the German philosopher Karl Löwith, the end of history was primarily a crisis of meaning and purpose regarding the direction of human existence; for Talmudic scholar and charismatic intellectual Jacob Taubes, it was the exhaustion of eschatological hopes, the last of which were vested in Marxism; for the French philosopher Emmanuel Mounier, the collapse of secular and religious faith; for the theologian Rudolf Bultmann, it meant that the task of finding meaning in human existence had become a purely individual burden; and for the political theorist Judith Shklar, it morphed into an “eschatological consciousness” that “extended from the merely cultural level” to the point where “all mankind is faced with its final hour.”

The end of history was not an idea that was original to Fukuyama; rather, as befits an age of ideological exhaustion, it was a vintage reissue harking back to an earlier era. The idea was hatched in the rubble of the Second World War and set the tone of intellectual life in the 1950s. Jacques Derrida once reminisced that it was the “daily bread” on which aspiring philosophers were raised back then. Its charismatic impresario was the Russian-born French philosopher Alexandre Kojève. Many others, however, came to terms with the idea the way one does with an ominous prognosis. For the German philosopher Karl Löwith, the end of history was primarily a crisis of meaning and purpose regarding the direction of human existence; for Talmudic scholar and charismatic intellectual Jacob Taubes, it was the exhaustion of eschatological hopes, the last of which were vested in Marxism; for the French philosopher Emmanuel Mounier, the collapse of secular and religious faith; for the theologian Rudolf Bultmann, it meant that the task of finding meaning in human existence had become a purely individual burden; and for the political theorist Judith Shklar, it morphed into an “eschatological consciousness” that “extended from the merely cultural level” to the point where “all mankind is faced with its final hour.” What do you give the queen who has everything? When Mark Antony was wondering how to impress Cleopatra in the run-up to the battle of Actium in 31BC, he knew that jewellery would hardly cut it. The queen of the Ptolemaic kingdom of Egypt had recently dissolved a giant pearl in vinegar and then proceeded to drink it, just because she could. In the face of such exhausted materialism, the Roman general knew that he would have to pull out the stops if he was to win over the woman with whom he was madly in love. So he arrived bearing 200,000 scrolls for the great library at Alexandria. On a logistical level this worked well: since the library was the biggest storehouse of books in the world, Cleopatra almost certainly had the shelf space. As a romantic gesture, it was equally provocative. Within weeks the middle-aged lovers were embarked on the final chapter of their erotic misadventure, the one which would mark the beginning of the end both for them and for Alexandria’s fabled library.

What do you give the queen who has everything? When Mark Antony was wondering how to impress Cleopatra in the run-up to the battle of Actium in 31BC, he knew that jewellery would hardly cut it. The queen of the Ptolemaic kingdom of Egypt had recently dissolved a giant pearl in vinegar and then proceeded to drink it, just because she could. In the face of such exhausted materialism, the Roman general knew that he would have to pull out the stops if he was to win over the woman with whom he was madly in love. So he arrived bearing 200,000 scrolls for the great library at Alexandria. On a logistical level this worked well: since the library was the biggest storehouse of books in the world, Cleopatra almost certainly had the shelf space. As a romantic gesture, it was equally provocative. Within weeks the middle-aged lovers were embarked on the final chapter of their erotic misadventure, the one which would mark the beginning of the end both for them and for Alexandria’s fabled library. A vacation in the Catskills, one of those beautiful summer days which seem to go on forever, with family friends down at a local pond. I must have been six. I waded around happily, in and out of the tall grasses that grew in the murky water, but when I emerged onto the shore my legs were studded with small black creatures. “Leeches! Don’t touch them!” my mother yelled. I stood terrified. My parents’ friends lit cigarettes and applied the glowing ends to the parasites, which exploded, showering me with blood.

A vacation in the Catskills, one of those beautiful summer days which seem to go on forever, with family friends down at a local pond. I must have been six. I waded around happily, in and out of the tall grasses that grew in the murky water, but when I emerged onto the shore my legs were studded with small black creatures. “Leeches! Don’t touch them!” my mother yelled. I stood terrified. My parents’ friends lit cigarettes and applied the glowing ends to the parasites, which exploded, showering me with blood.