Andrea Wulf in Aeon:

In September 1798, one day after their poem collection Lyrical Ballads was published, the poets Samuel Taylor Coleridge and William Wordsworth sailed from Yarmouth, on the Norfolk coast, to Hamburg in the far north of the German states. Coleridge had spent the previous few months preparing for what he called ‘my German expedition’. The realisation of the scheme, he explained to a friend, was of the highest importance to ‘my intellectual utility; and of course to my moral happiness’. He wanted to master the German language and meet the thinkers and writers who lived in Jena, a small university town, southwest of Berlin. On Thomas Poole’s advice, his motto had been: ‘Speak nothing but German. Live with Germans. Read in German. Think in German.’

In September 1798, one day after their poem collection Lyrical Ballads was published, the poets Samuel Taylor Coleridge and William Wordsworth sailed from Yarmouth, on the Norfolk coast, to Hamburg in the far north of the German states. Coleridge had spent the previous few months preparing for what he called ‘my German expedition’. The realisation of the scheme, he explained to a friend, was of the highest importance to ‘my intellectual utility; and of course to my moral happiness’. He wanted to master the German language and meet the thinkers and writers who lived in Jena, a small university town, southwest of Berlin. On Thomas Poole’s advice, his motto had been: ‘Speak nothing but German. Live with Germans. Read in German. Think in German.’

After a few days in Hamburg, Coleridge realised he didn’t have enough money to travel the 300 miles south to Jena and Weimar, and instead he spent almost five months in nearby Ratzeburg, then studied for several months in Göttingen. He soon spoke German. Though he deemed his pronunciation ‘hideous’, his knowledge of the language was so good that he would later translate Friedrich Schiller’s drama Wallenstein (1800) and Goethe’s Faust (1808). Those 10 months in Germany marked a turning point in Coleridge’s life. He had left England as a poet but returned with the mind of a philosopher – and a trunk full of philosophical books.

More here.

Females, on average, are better than males at putting themselves in others’ shoes and imagining what the other person is thinking or feeling, suggests a new study of over 300,000 people in 57 countries.

Females, on average, are better than males at putting themselves in others’ shoes and imagining what the other person is thinking or feeling, suggests a new study of over 300,000 people in 57 countries. The U.S. use of nuclear weapons against Japan during World War II has long been a subject of emotional debate. Initially, few questioned President Truman’s decision to drop two atomic bombs, on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. But, in 1965, historian Gar Alperovitz argued that, although the bombs did force an immediate end to the war, Japan’s leaders had wanted to surrender anyway and likely would have done so before the American invasion planned for Nov. 1. Their use was, therefore, unnecessary. Obviously, if the bombings weren’t necessary to win the war, then bombing Hiroshima and Nagasaki was wrong. In the 48 years since, many others have joined the fray: some echoing Alperovitz and denouncing the bombings, others rejoining hotly that the bombings were moral, necessary, and life-saving.

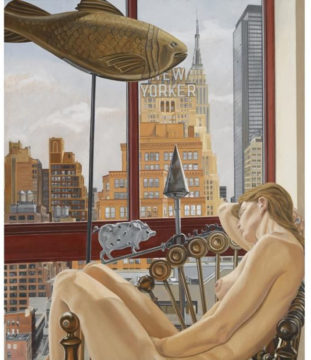

The U.S. use of nuclear weapons against Japan during World War II has long been a subject of emotional debate. Initially, few questioned President Truman’s decision to drop two atomic bombs, on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. But, in 1965, historian Gar Alperovitz argued that, although the bombs did force an immediate end to the war, Japan’s leaders had wanted to surrender anyway and likely would have done so before the American invasion planned for Nov. 1. Their use was, therefore, unnecessary. Obviously, if the bombings weren’t necessary to win the war, then bombing Hiroshima and Nagasaki was wrong. In the 48 years since, many others have joined the fray: some echoing Alperovitz and denouncing the bombings, others rejoining hotly that the bombings were moral, necessary, and life-saving. FROM THE OUTSET, Pearlstein has occupied an anomalous position within his generation, for he has been not only the most uncompromising exponent of an unpopular style but its most visible and possibly most successful practitioner. In large measure, Pearlstein owes his special status among fellow Realists and within the art world generally to his gift for ideas and advocacy. It was more by force of argument than by example that he was able in the early 1960s to place a supposedly marginal concern—painting the figure from life—somewhere near the center of critical debate, and to link his cause to that of other artists, many of them abstractionists, who were faced with the task of sorting out the debris left by the first wave of Abstract Expressionism.

FROM THE OUTSET, Pearlstein has occupied an anomalous position within his generation, for he has been not only the most uncompromising exponent of an unpopular style but its most visible and possibly most successful practitioner. In large measure, Pearlstein owes his special status among fellow Realists and within the art world generally to his gift for ideas and advocacy. It was more by force of argument than by example that he was able in the early 1960s to place a supposedly marginal concern—painting the figure from life—somewhere near the center of critical debate, and to link his cause to that of other artists, many of them abstractionists, who were faced with the task of sorting out the debris left by the first wave of Abstract Expressionism. A FEW YEARS AGO, while flipping through the new arrivals crate at Nice Price Records in Raleigh, North Carolina, where I was visiting family over the holidays, I became transfixed by what I heard playing on the store’s stereo system. It was immediately recognizable as Christmas music: A jubilant, resonant male baritone implored the listener to “let me hang my mistletoe over your head / and let me love you.” But the voice, landing somewhere between the velvet burliness of Teddy Pendergrass and the genteel phrasing of Lou Rawls, like the lustrous production and extravagant, modern R&B arrangement, which included female backup singers who swooned along to the singer’s seductive caroling, seemed unlocatable. Likewise, the song, a lurching minor-key slow jam in 3/4 time, had a weird melancholia at odds with the enforced buoyancy of the holiday season even as it summoned a long tradition of holiday music, such as “Have Yourself a Merry Little Christmas” and “Blue Christmas,” that expresses how cheery expectations at year’s end can often yield an aching emptiness. Amid these mixed messages and sundry stylistic signals, it was hard to tell if the song was festive burlesque or heartfelt holiday paean. I was intrigued, to say the least.

A FEW YEARS AGO, while flipping through the new arrivals crate at Nice Price Records in Raleigh, North Carolina, where I was visiting family over the holidays, I became transfixed by what I heard playing on the store’s stereo system. It was immediately recognizable as Christmas music: A jubilant, resonant male baritone implored the listener to “let me hang my mistletoe over your head / and let me love you.” But the voice, landing somewhere between the velvet burliness of Teddy Pendergrass and the genteel phrasing of Lou Rawls, like the lustrous production and extravagant, modern R&B arrangement, which included female backup singers who swooned along to the singer’s seductive caroling, seemed unlocatable. Likewise, the song, a lurching minor-key slow jam in 3/4 time, had a weird melancholia at odds with the enforced buoyancy of the holiday season even as it summoned a long tradition of holiday music, such as “Have Yourself a Merry Little Christmas” and “Blue Christmas,” that expresses how cheery expectations at year’s end can often yield an aching emptiness. Amid these mixed messages and sundry stylistic signals, it was hard to tell if the song was festive burlesque or heartfelt holiday paean. I was intrigued, to say the least. Ethan Frome is not your typical festive book. There are no fabulous parties or thawed hearts, no warming morals about the power of togetherness realised with a fireplace crackling somewhere in the background. In fact, Edith Wharton’s 1911 novella is a melancholy, mean little story, as chilly in tone as the lonely Massachusetts landscape with its “sheet of snow perpetually renewed from … pale skies”. And yet, there’s something in it that makes it a perfect read for those slushy days between Christmas and new year. Perhaps it’s the length: short enough to be consumed in one or two sittings, gulped down like ice water. Perhaps it’s the growing sense of foreboding, ideal for those who prefer their December reading to be of the truly bleak midwinter variety (or anyone in need of a palate cleanser after all that yuletide indulgence).

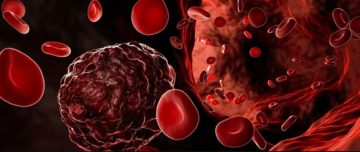

Ethan Frome is not your typical festive book. There are no fabulous parties or thawed hearts, no warming morals about the power of togetherness realised with a fireplace crackling somewhere in the background. In fact, Edith Wharton’s 1911 novella is a melancholy, mean little story, as chilly in tone as the lonely Massachusetts landscape with its “sheet of snow perpetually renewed from … pale skies”. And yet, there’s something in it that makes it a perfect read for those slushy days between Christmas and new year. Perhaps it’s the length: short enough to be consumed in one or two sittings, gulped down like ice water. Perhaps it’s the growing sense of foreboding, ideal for those who prefer their December reading to be of the truly bleak midwinter variety (or anyone in need of a palate cleanser after all that yuletide indulgence). Typically, if a cell gets squeezed too hard, it dies. But for a metastasizing cancer cell, the process of squeezing through the narrow channels of the circulatory system may trigger a series of mutations that help the cell stave off programmed cell death while also evading the immune system, according to in vitro and mouse research published in

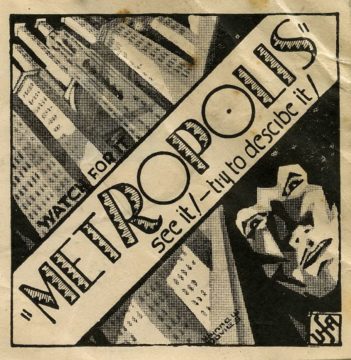

Typically, if a cell gets squeezed too hard, it dies. But for a metastasizing cancer cell, the process of squeezing through the narrow channels of the circulatory system may trigger a series of mutations that help the cell stave off programmed cell death while also evading the immune system, according to in vitro and mouse research published in  Nabokov loved film, hopelessly. As a young writer in Weimar exile, this Russian aristocrat and Cambridge graduate rented Berlin apartments amidst the city’s countless movie theaters and neon signs, becoming a regular moviegoer. He was less a connoisseur than an avid consumer. Nabokov’s absorption of this mass of films — mostly forgettable, many lost — made him an authority on cinema in the aggregate. It is to these genre films, these sequels and knockoffs, that Nabokov responds in his poem “The Cinema” (“Kinematograf”), and not to the film art and auteur cinema of retrospective accounts. The setting here is not a grandiose premiere in a movie palace. Instead, we are in a corner theater watching a run-of-the-mill American or German release, another product of the Weimar and Hollywood film factories which together accounted for nearly all the films seen by the young émigré in Berlin. Seated among German salesclerks, Nabokov is both charmed and amused. As by all accounts he was in real life: a contemporary recalled the 20-something Nabokov laughing so hard at American slapstick that, choking and shaking with mirth, he had to leave the screening.

Nabokov loved film, hopelessly. As a young writer in Weimar exile, this Russian aristocrat and Cambridge graduate rented Berlin apartments amidst the city’s countless movie theaters and neon signs, becoming a regular moviegoer. He was less a connoisseur than an avid consumer. Nabokov’s absorption of this mass of films — mostly forgettable, many lost — made him an authority on cinema in the aggregate. It is to these genre films, these sequels and knockoffs, that Nabokov responds in his poem “The Cinema” (“Kinematograf”), and not to the film art and auteur cinema of retrospective accounts. The setting here is not a grandiose premiere in a movie palace. Instead, we are in a corner theater watching a run-of-the-mill American or German release, another product of the Weimar and Hollywood film factories which together accounted for nearly all the films seen by the young émigré in Berlin. Seated among German salesclerks, Nabokov is both charmed and amused. As by all accounts he was in real life: a contemporary recalled the 20-something Nabokov laughing so hard at American slapstick that, choking and shaking with mirth, he had to leave the screening. In the last decade, sweeping mainstream-media claims about epigenetics’ expansive role in shaping our world have become hard to escape. I am a geneticist and happy to stipulate that epigenetics is responsible for a considerable amount of our planet’s dazzling biological complexity. And yet when someone comes at me with explanations of anything social and behavioral in humans predicated on epigenetic effects, I cringe like an astronomer informed that planetary dynamics determine my personal character (typical Capricorn hubris they might say). The details of your star chart might be precisely correct, yet I don’t have to tell you that no astronomer seriously ascribes comparable validity to astrology and astronomy. Epigenetics is a powerful and ubiquitous process in biology but entails no mechanism equipped to explain any of the multi-generational psychological phenomena it’s called upon to legitimize in media coverage, claims about which are both reliably overblown and entirely speculative. Let’s inventory epigenetics’ actual reach and influence; you can arrive at your own conclusions about whether it is plausibly, as headlines often claim, the transmission mechanism for such phenomena in humans as “intergenerational trauma.”

In the last decade, sweeping mainstream-media claims about epigenetics’ expansive role in shaping our world have become hard to escape. I am a geneticist and happy to stipulate that epigenetics is responsible for a considerable amount of our planet’s dazzling biological complexity. And yet when someone comes at me with explanations of anything social and behavioral in humans predicated on epigenetic effects, I cringe like an astronomer informed that planetary dynamics determine my personal character (typical Capricorn hubris they might say). The details of your star chart might be precisely correct, yet I don’t have to tell you that no astronomer seriously ascribes comparable validity to astrology and astronomy. Epigenetics is a powerful and ubiquitous process in biology but entails no mechanism equipped to explain any of the multi-generational psychological phenomena it’s called upon to legitimize in media coverage, claims about which are both reliably overblown and entirely speculative. Let’s inventory epigenetics’ actual reach and influence; you can arrive at your own conclusions about whether it is plausibly, as headlines often claim, the transmission mechanism for such phenomena in humans as “intergenerational trauma.” The current mainstream narrative in the United States holds that democracy is under threat from MAGA zealots, election deniers, and Republicans who are threatening to ignore unfavorable results (as well as recruiting loyalists to oversee elections and

The current mainstream narrative in the United States holds that democracy is under threat from MAGA zealots, election deniers, and Republicans who are threatening to ignore unfavorable results (as well as recruiting loyalists to oversee elections and  Todd Rundgren, the record producer, sound engineer, songwriter, and recording artist, has had such a strange career in the music business that it somehow does not seem strange that, at seventy-four, he has been performing in a David Bowie tribute band. This on the heels of a few Beatles-tribute tours. A giant covering giants.

Todd Rundgren, the record producer, sound engineer, songwriter, and recording artist, has had such a strange career in the music business that it somehow does not seem strange that, at seventy-four, he has been performing in a David Bowie tribute band. This on the heels of a few Beatles-tribute tours. A giant covering giants. After Bunny’s arrangement with Paul was established, she went on to flower artistically. Partly schooled by John Fowler, of the London interior design firm of Colefax & Fowler, she cast a spell on all seven of her residences—including ones in Nantucket, Washington, D.C., and New York City. In this phase, too, she championed and collaborated with a long line of gay visual artists. These relationships took the form of “violent crushes”; each of them, for her, was a kind of romance. And one, the gifted French jewelry designer Jean Schlumberger—”the black cat,” she called him—is rumored to have been her lover in the early 1950s. He escorted her to Paris, where she attended the haute couture collections for the first time. Once “perilously close to dowdy,” Griswold writes, Bunny was transformed. She became a style icon, seemingly overnight, thanks to her new, romance-tinged friendships with two famed fashion designers, Cristóbal Balenciaga and Hubert de Givenchy. The latter brought Bunny into Paris’s haut monde. She purchased an apartment on the Avenue Foch and basked in the attention of a chic new crowd she called her “French family.” The courtly Givenchy steered Bunny toward one of her most celebrated projects—her impeccable restoration of the 1678 Potager de Roi, Louis XIV’s kitchen garden at Versailles, which had long fallen into desuetude.

After Bunny’s arrangement with Paul was established, she went on to flower artistically. Partly schooled by John Fowler, of the London interior design firm of Colefax & Fowler, she cast a spell on all seven of her residences—including ones in Nantucket, Washington, D.C., and New York City. In this phase, too, she championed and collaborated with a long line of gay visual artists. These relationships took the form of “violent crushes”; each of them, for her, was a kind of romance. And one, the gifted French jewelry designer Jean Schlumberger—”the black cat,” she called him—is rumored to have been her lover in the early 1950s. He escorted her to Paris, where she attended the haute couture collections for the first time. Once “perilously close to dowdy,” Griswold writes, Bunny was transformed. She became a style icon, seemingly overnight, thanks to her new, romance-tinged friendships with two famed fashion designers, Cristóbal Balenciaga and Hubert de Givenchy. The latter brought Bunny into Paris’s haut monde. She purchased an apartment on the Avenue Foch and basked in the attention of a chic new crowd she called her “French family.” The courtly Givenchy steered Bunny toward one of her most celebrated projects—her impeccable restoration of the 1678 Potager de Roi, Louis XIV’s kitchen garden at Versailles, which had long fallen into desuetude. On 11 July, in a live broadcast from the White House, U.S. President Joe Biden unveiled the first image from what he called a “miraculous” new space telescope. Along with millions of people around the world, he marveled at a crush of thousands of galaxies, some seen as they were 13 billion years ago. “It’s hard to even fathom,” Biden said.

On 11 July, in a live broadcast from the White House, U.S. President Joe Biden unveiled the first image from what he called a “miraculous” new space telescope. Along with millions of people around the world, he marveled at a crush of thousands of galaxies, some seen as they were 13 billion years ago. “It’s hard to even fathom,” Biden said. In 1788, as the young republic was trying to establish itself under the new Constitution,

In 1788, as the young republic was trying to establish itself under the new Constitution,