Kenneth L. Woodward and Jean-Luc Marion at Commonweal:

KW: Many philosophers have said that a certain attitude is required in order to philosophize. For example, the neo-Thomist Josef Pieper said a philosopher had to have a sense of wonder. Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel said “radical amazement” is required. You have said the capacity to be astonished is essential. What do you mean by astonishment?

KW: Many philosophers have said that a certain attitude is required in order to philosophize. For example, the neo-Thomist Josef Pieper said a philosopher had to have a sense of wonder. Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel said “radical amazement” is required. You have said the capacity to be astonished is essential. What do you mean by astonishment?

JLM: Good question. If I may be a bit polemical, I would say that the greatest possible failure for a professional philosopher is never to be astonished. And many philosophers are in that situation. They philosophize using a set of concepts or tools that protect them against encountering anything new. They have enough ways to make any question lead to a (pre-determined) answer, or even to disappear. But my experience of philosophy—and it’s why people like Descartes or Heidegger were so important—is that philosophy begins when you have this gift of a question that resists an answer. By “answer,” I mean one that is based on what was known before that question was asked. A new question opens up a new landscape that you cannot walk through unless you get a new pair of shoes.

more here.

When Norman Mailer was inducted into the Army, in March, 1944, he was a freshly married twenty-one-year-old Harvard graduate, a slight young man of five feet eight inches and a hundred and thirty-five pounds. In the previous few years, he had published some stories and written a play and two novels (one of them published, in a typescript facsimile, as “

When Norman Mailer was inducted into the Army, in March, 1944, he was a freshly married twenty-one-year-old Harvard graduate, a slight young man of five feet eight inches and a hundred and thirty-five pounds. In the previous few years, he had published some stories and written a play and two novels (one of them published, in a typescript facsimile, as “ The twin books of Egyptian poet Yahia Lababidi— Learning to Pray: A Book of Longing and Desert Songs, published in 2021 and 2022, respectively—uphold the Sufi tradition that was critical in shaping the imagery, symbolism, metaphors, tropes, and indeed the world view, of classical Sufi poetry and portray mercy with a pluralistic vision by upholding an expression of love above all divides. Lababidi does this by the clean magic of his language, relatable imagery and fine craft.

The twin books of Egyptian poet Yahia Lababidi— Learning to Pray: A Book of Longing and Desert Songs, published in 2021 and 2022, respectively—uphold the Sufi tradition that was critical in shaping the imagery, symbolism, metaphors, tropes, and indeed the world view, of classical Sufi poetry and portray mercy with a pluralistic vision by upholding an expression of love above all divides. Lababidi does this by the clean magic of his language, relatable imagery and fine craft. Democrats did so well, in part, because a conservative Supreme Court handed them a political gift by overturning Roe v. Wade and Republicans ran a group of dreadful celebrity Senate candidates.

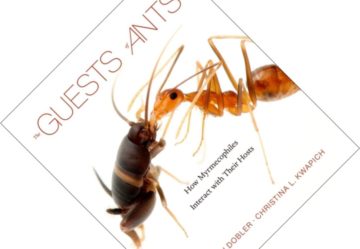

Democrats did so well, in part, because a conservative Supreme Court handed them a political gift by overturning Roe v. Wade and Republicans ran a group of dreadful celebrity Senate candidates. It has to be one of the more delightful details of the natural world: the ecosystem of an ant’s nest is home to its own constellation of creatures that specialise in living within or nearby it. Daniel Kronauer’s book

It has to be one of the more delightful details of the natural world: the ecosystem of an ant’s nest is home to its own constellation of creatures that specialise in living within or nearby it. Daniel Kronauer’s book  “Everyone has their beliefs and cultures. We welcome and respect that. All we ask is that other people do the same for us.” So

“Everyone has their beliefs and cultures. We welcome and respect that. All we ask is that other people do the same for us.” So  As these debates about identity and representation in American education were raging throughout the twentieth century, a second major shift was taking place. The central belief of Horace Mann and Catharine Beecher—that the point of education was to purify young souls—gradually gave way to a more utilitarian calculation that schools, first and foremost, were places to gain the skills that were valued in an increasingly competitive labor market. By 1972, when Gallup asked American parents why they wanted their children to be educated, the most frequent response was “to get better jobs”; “to make more money” was the third.

As these debates about identity and representation in American education were raging throughout the twentieth century, a second major shift was taking place. The central belief of Horace Mann and Catharine Beecher—that the point of education was to purify young souls—gradually gave way to a more utilitarian calculation that schools, first and foremost, were places to gain the skills that were valued in an increasingly competitive labor market. By 1972, when Gallup asked American parents why they wanted their children to be educated, the most frequent response was “to get better jobs”; “to make more money” was the third. It’s no secret, among political junkies anyway, that Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell and much of the Republican elite have been casting around for a way to derail Donald Trump’s bid to be the 2024 GOP presidential nominee. It’s a delicate operation, to be certain. Trump’s allure to the GOP primary voting base isn’t just that he triggers the liberals, but that he ruffles the feathers of the Republican establishment. It makes the deplorables feel powerful, watching people like McConnell and House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy bow and scrape to the ludicrous reality TV host foisted on them by their own voters. So the strategy is always about trying to find some way to undermine Trump without provoking him to unload personal invective on Truth Social in retaliation.

It’s no secret, among political junkies anyway, that Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell and much of the Republican elite have been casting around for a way to derail Donald Trump’s bid to be the 2024 GOP presidential nominee. It’s a delicate operation, to be certain. Trump’s allure to the GOP primary voting base isn’t just that he triggers the liberals, but that he ruffles the feathers of the Republican establishment. It makes the deplorables feel powerful, watching people like McConnell and House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy bow and scrape to the ludicrous reality TV host foisted on them by their own voters. So the strategy is always about trying to find some way to undermine Trump without provoking him to unload personal invective on Truth Social in retaliation. T

T To find mirth in the world is to be human.

To find mirth in the world is to be human. Psychically, Geuss argues, liberalism offers “the fantasy of being an entirely sovereign individual” as “a reaction to massive anxiety about real loss of agency in the world.” It offers the false security of “living in a bubble of nostalgia” for the international economic hegemony that the United States began to lose from the mid-1960s onwards, first as other economies recovered from the devastations of World War II and then with increasing globalization, job flight, Trumpism, and Brexit. In this situation, liberalism “responds in a particularly satisfactory way to deep human needs and to the vested interests of powerful economic and social groups.”

Psychically, Geuss argues, liberalism offers “the fantasy of being an entirely sovereign individual” as “a reaction to massive anxiety about real loss of agency in the world.” It offers the false security of “living in a bubble of nostalgia” for the international economic hegemony that the United States began to lose from the mid-1960s onwards, first as other economies recovered from the devastations of World War II and then with increasing globalization, job flight, Trumpism, and Brexit. In this situation, liberalism “responds in a particularly satisfactory way to deep human needs and to the vested interests of powerful economic and social groups.” Memory and perception seem like entirely distinct experiences, and neuroscientists used to be confident that the brain produced them differently, too. But in the 1990s neuroimaging studies revealed that parts of the brain that were thought to be active only during sensory perception are also active during the recall of memories.

Memory and perception seem like entirely distinct experiences, and neuroscientists used to be confident that the brain produced them differently, too. But in the 1990s neuroimaging studies revealed that parts of the brain that were thought to be active only during sensory perception are also active during the recall of memories. This is the promise of medical assistance in dying: that vulnerable people who want to die for the wrong reasons will be encouraged to live, as they always have been — while people who want to die for the right reasons will have their autonomous decision upheld. If even a single vulnerable person were pushed into assisted death, it would be a scandal to the system. That is why safeguards were put into place.

This is the promise of medical assistance in dying: that vulnerable people who want to die for the wrong reasons will be encouraged to live, as they always have been — while people who want to die for the right reasons will have their autonomous decision upheld. If even a single vulnerable person were pushed into assisted death, it would be a scandal to the system. That is why safeguards were put into place.