Andrew Prokop in Vox:

The way Dominion’s attorneys tell the story, the problem really started when, late on election night, Fox News’s decision desk called the state of Arizona for Joe Biden — and no other networks joined them. The Fox call was consequential, seriously undercutting Trump’s hope of portraying the election outcome as genuinely in question. It also was, probably, premature. The consensus among other decision desks and election wonks was that Fox called the state too quickly, considering how much of the vote remained uncounted and where and whom those uncounted votes were coming from. Other outlets left Arizona uncalled for more than a week as counting continued, and Biden’s lead shrank there. Biden eventually won the state by a mere 0.3 percent margin.

The way Dominion’s attorneys tell the story, the problem really started when, late on election night, Fox News’s decision desk called the state of Arizona for Joe Biden — and no other networks joined them. The Fox call was consequential, seriously undercutting Trump’s hope of portraying the election outcome as genuinely in question. It also was, probably, premature. The consensus among other decision desks and election wonks was that Fox called the state too quickly, considering how much of the vote remained uncounted and where and whom those uncounted votes were coming from. Other outlets left Arizona uncalled for more than a week as counting continued, and Biden’s lead shrank there. Biden eventually won the state by a mere 0.3 percent margin.

But the Fox personalities’ real concern was not so much with the facts or technical details of election wonkery as with the optics. In getting out on a limb and calling Arizona for Biden when no one else was doing so, it appeared to Fox’s pro-Trump viewers like the network was shivving Trump. “We worked really hard to build what we have. Those fuckers [at the decision desk] are destroying our credibility. It enrages me,” Fox News host Tucker Carlson wrote to his producer on November 5. He went on to say that what Trump is good at is “destroying things,” adding, “He could easily destroy us if we play it wrong.”

On November 7, Carlson again wrote to his producer when Fox called Biden as the winner nationally (this time, alongside the other major networks). “Do the executives understand how much credibility and trust we’ve lost with our audience? We’re playing with fire, for real,” he wrote.

The fear of alienating the audience was particularly acute because another conservative cable network with a more conspiratorial bent, Newsmax, was covering Trump’s stolen election claims far more uncritically. “An alternative like newsmax could be devastating to us,” Carlson continued.

Fox News anchor Dana Perino wrote to a Republican strategist about “this RAGING issue about fox losing tons of viewers and many watching — get this — newsmax! Our viewers are so mad about the election calls…” And Fox News CEO Suzanne Scott told another executive that the political team did not understand “the impact to the brand and the arrogance in calling AZ.”

More here.

Social Security is back in the news. Some Republicans are angling to reduce benefits, while Democrats are posing as the valiant saviors of the popular program. The end result, most likely, is that nothing will happen. We have seen this story before, because this is roughly where the politics of Social Security have been stuck for about forty years. It’s a problem because the system truly does need repair, and the endless conflict between debt-obsessed Republicans and stalwart Democrats will not generate the progressive reforms we need.

Social Security is back in the news. Some Republicans are angling to reduce benefits, while Democrats are posing as the valiant saviors of the popular program. The end result, most likely, is that nothing will happen. We have seen this story before, because this is roughly where the politics of Social Security have been stuck for about forty years. It’s a problem because the system truly does need repair, and the endless conflict between debt-obsessed Republicans and stalwart Democrats will not generate the progressive reforms we need.

Magnificent Rebels revels in minutiae. But it also has a grander point to make. It wants to ask the big question — “why we are who we are.” The first step in answering this “is to look at us as individuals — when did we begin to be as selfish as we are today?” For Wulf, Jena is at the heart of this story: the Jena Set, we are to learn, was “bound by an obsession with the free self at a time when most of the world was ruled by monarchs and leaders who controlled many aspects of their subjects’ lives.” And so, they “invented” the self.

Magnificent Rebels revels in minutiae. But it also has a grander point to make. It wants to ask the big question — “why we are who we are.” The first step in answering this “is to look at us as individuals — when did we begin to be as selfish as we are today?” For Wulf, Jena is at the heart of this story: the Jena Set, we are to learn, was “bound by an obsession with the free self at a time when most of the world was ruled by monarchs and leaders who controlled many aspects of their subjects’ lives.” And so, they “invented” the self. Red Memory is not just an engagingly written book but also, for two reasons, a much-needed one. It is valuable, first, because it helps clear up lingering popular misunderstandings of a major event in Chinese history. The Cultural Revolution and its legacy have generated a rich scholarly literature, which Branigan mines. But many non-specialists still have a vision of it formed by one or two moving memoirs they have read. The problem is that some of the most influential of these make it easy for readers to assume that China’s population is made up of two groups: former Cultural Revolution perpetrators and their descendants and former Cultural Revolution victims and their descendants. In fact, the twists and turns of the event were such that many people were perpetrators at one point and victims at another. Many families had members who moved between these two categories.

Red Memory is not just an engagingly written book but also, for two reasons, a much-needed one. It is valuable, first, because it helps clear up lingering popular misunderstandings of a major event in Chinese history. The Cultural Revolution and its legacy have generated a rich scholarly literature, which Branigan mines. But many non-specialists still have a vision of it formed by one or two moving memoirs they have read. The problem is that some of the most influential of these make it easy for readers to assume that China’s population is made up of two groups: former Cultural Revolution perpetrators and their descendants and former Cultural Revolution victims and their descendants. In fact, the twists and turns of the event were such that many people were perpetrators at one point and victims at another. Many families had members who moved between these two categories. My dad always flew an American flag in our front yard. The blue paint on our two-story house was perennially chipping; the fence, or the rail by the stairs, or the front door, existed in a perpetual state of disrepair, but that flag always flew pristine. Our corner lot, which had been redlined by the federal government, was along the river that divided the black side from the white side of our Iowa town. At the edge of our lawn, high on an aluminum pole, soared the flag, which my dad would replace as soon as it showed the slightest tatter.

My dad always flew an American flag in our front yard. The blue paint on our two-story house was perennially chipping; the fence, or the rail by the stairs, or the front door, existed in a perpetual state of disrepair, but that flag always flew pristine. Our corner lot, which had been redlined by the federal government, was along the river that divided the black side from the white side of our Iowa town. At the edge of our lawn, high on an aluminum pole, soared the flag, which my dad would replace as soon as it showed the slightest tatter. The problem with trees is that they are too slow.

The problem with trees is that they are too slow. Was there really a colony known as “Libertalia”, founded by Enlightened pirates on the north-east coast of Madagascar in the early 18th century?

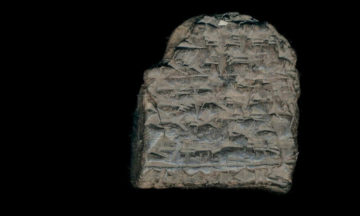

Was there really a colony known as “Libertalia”, founded by Enlightened pirates on the north-east coast of Madagascar in the early 18th century? I was sitting in a quiet office in the Louvre Museum in Paris, a clay tablet in my hand, using a magnifying glass to make out words that had been inscribed on it in small, careful, wedge-shaped signs known as cuneiform. It looked diminutive in my palm, just

I was sitting in a quiet office in the Louvre Museum in Paris, a clay tablet in my hand, using a magnifying glass to make out words that had been inscribed on it in small, careful, wedge-shaped signs known as cuneiform. It looked diminutive in my palm, just  Cities are incredibly important to modern life, and their importance is only growing. As

Cities are incredibly important to modern life, and their importance is only growing. As  Steven Pinker thinks ChatGPT is truly impressive — and will be even more so once it “stops making stuff up” and becomes less error-prone. Higher education, indeed, much of the world, was set abuzz in November when OpenAI unveiled its ChatGPT chatbot capable of instantly answering questions (in fact, composing writing in various genres) across a range of fields in a conversational and ostensibly authoritative fashion. Utilizing a type of AI called a large language model (LLM), ChatGPT is able to continuously learn and improve its responses. But just how good can it get?

Steven Pinker thinks ChatGPT is truly impressive — and will be even more so once it “stops making stuff up” and becomes less error-prone. Higher education, indeed, much of the world, was set abuzz in November when OpenAI unveiled its ChatGPT chatbot capable of instantly answering questions (in fact, composing writing in various genres) across a range of fields in a conversational and ostensibly authoritative fashion. Utilizing a type of AI called a large language model (LLM), ChatGPT is able to continuously learn and improve its responses. But just how good can it get?  The way Dominion’s attorneys tell the story, the problem really started when, late on election night, Fox News’s decision desk called the state of Arizona for Joe Biden — and no other networks joined them. The Fox call was consequential, seriously undercutting Trump’s hope of portraying the election outcome as genuinely in question. It also was, probably, premature. The consensus among other decision desks and election wonks was that Fox called the state too quickly, considering how much of the vote remained uncounted and where and whom those uncounted votes were coming from. Other outlets left Arizona uncalled

The way Dominion’s attorneys tell the story, the problem really started when, late on election night, Fox News’s decision desk called the state of Arizona for Joe Biden — and no other networks joined them. The Fox call was consequential, seriously undercutting Trump’s hope of portraying the election outcome as genuinely in question. It also was, probably, premature. The consensus among other decision desks and election wonks was that Fox called the state too quickly, considering how much of the vote remained uncounted and where and whom those uncounted votes were coming from. Other outlets left Arizona uncalled  On Jan. 28, 2019, Nikole Hannah-Jones, who has been a staff writer at The New York Times Magazine since 2015, came to one of our weekly ideas meetings with a very big idea. My notes from the meeting simply say, “NIKOLE: special issue on the 400th anniversary of African slaves coming to U.S.,” a milestone that was approaching that August. This wasn’t the first time Nikole had brought up 1619. As an investigative journalist who often focuses on racial inequalities in education, Nikole has frequently turned to history to explain the present. Sometimes, reading a draft of one of her articles, I’d ask if she might include even more history, to which she would remark that if I gave her more space, she would be happy to take it all the way back to 1619. This was a running joke, but it was also a reflection of how Nikole had been cultivating the idea for what became

On Jan. 28, 2019, Nikole Hannah-Jones, who has been a staff writer at The New York Times Magazine since 2015, came to one of our weekly ideas meetings with a very big idea. My notes from the meeting simply say, “NIKOLE: special issue on the 400th anniversary of African slaves coming to U.S.,” a milestone that was approaching that August. This wasn’t the first time Nikole had brought up 1619. As an investigative journalist who often focuses on racial inequalities in education, Nikole has frequently turned to history to explain the present. Sometimes, reading a draft of one of her articles, I’d ask if she might include even more history, to which she would remark that if I gave her more space, she would be happy to take it all the way back to 1619. This was a running joke, but it was also a reflection of how Nikole had been cultivating the idea for what became  Advait Arun in Phenomenal World’s The Polycrisis:

Advait Arun in Phenomenal World’s The Polycrisis: Ira Katznelson in Boston Review:

Ira Katznelson in Boston Review: