From Delancey Place:

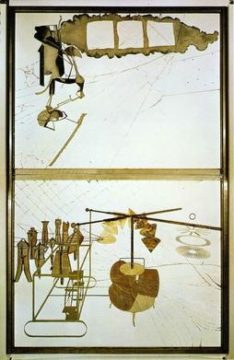

“Marcel Duchamp (1887-1968), the younger brother of the sculptor Duchamp-Villon, was perhaps the most stimulating intellectual to be concerned with the visual arts in the twentieth century — ironic, witty and penetrating. He was also a born anarchist. Like his brother, he began (after some exploratory years in various current styles) with a dynamic Futurist version of Cubism, of which his painting Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2 is the best known example. It caused a scandal at the famous Armory Show of modern art in New York in 1913. Duchamp’s ready-mades are everyday manufactured objects converted into works of art simply by the artist’s act of choosing them. Duchamp did nothing to them except present them for contemplation as ‘art’. They represent in many ways the most iconoclastic gesture that any artist has ever made — a gesture of total rejection and revolt against accepted artistic canons. For by reducing the creative act simply to one of choice ‘ready-mades’ discredit the ‘work of art’ and the taste, skill, craftsmanship — not to mention any higher artistic values — that it traditionally embodies. Duchamp insisted again and again that his ‘choice of these ready-mades was never dictated by an aesthetic delectation. The choice was based on a reaction of visual indifference, with at the same time a total absence of good or bad taste, in fact a complete anaesthesia.’

“Marcel Duchamp (1887-1968), the younger brother of the sculptor Duchamp-Villon, was perhaps the most stimulating intellectual to be concerned with the visual arts in the twentieth century — ironic, witty and penetrating. He was also a born anarchist. Like his brother, he began (after some exploratory years in various current styles) with a dynamic Futurist version of Cubism, of which his painting Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2 is the best known example. It caused a scandal at the famous Armory Show of modern art in New York in 1913. Duchamp’s ready-mades are everyday manufactured objects converted into works of art simply by the artist’s act of choosing them. Duchamp did nothing to them except present them for contemplation as ‘art’. They represent in many ways the most iconoclastic gesture that any artist has ever made — a gesture of total rejection and revolt against accepted artistic canons. For by reducing the creative act simply to one of choice ‘ready-mades’ discredit the ‘work of art’ and the taste, skill, craftsmanship — not to mention any higher artistic values — that it traditionally embodies. Duchamp insisted again and again that his ‘choice of these ready-mades was never dictated by an aesthetic delectation. The choice was based on a reaction of visual indifference, with at the same time a total absence of good or bad taste, in fact a complete anaesthesia.’

More here.

Sigrid Undset was an unlikely literary star. Modernist themes were on the ascendancy in those days, but she wanted to write medieval romances. So at night, after work, she researched her subject, studying the sagas, old ballads, and chronicles of the Middle Ages.

Sigrid Undset was an unlikely literary star. Modernist themes were on the ascendancy in those days, but she wanted to write medieval romances. So at night, after work, she researched her subject, studying the sagas, old ballads, and chronicles of the Middle Ages.

In “Victory City,” a new novel by Salman Rushdie, a gifted storyteller and poet creates a new civilization through the sheer power of her imagination. Blessed by a goddess, she lives nearly 240 years, long enough to witness the rise and fall of her empire in southern India, but her lasting legacy is an epic poem.

In “Victory City,” a new novel by Salman Rushdie, a gifted storyteller and poet creates a new civilization through the sheer power of her imagination. Blessed by a goddess, she lives nearly 240 years, long enough to witness the rise and fall of her empire in southern India, but her lasting legacy is an epic poem. The wolves reintroduced to Yellowstone National Park in 1995 are some of the best-studied mammals on the planet. Biological technician and park ranger Rick McIntyre has spent over two decades scrutinising their daily lives, venturing into the park every single day. Where his

The wolves reintroduced to Yellowstone National Park in 1995 are some of the best-studied mammals on the planet. Biological technician and park ranger Rick McIntyre has spent over two decades scrutinising their daily lives, venturing into the park every single day. Where his  Military artificial intelligence (AI)-enabled technology might still be in the relatively fledgling stages but the debate on how to regulate its use is already in full swing. Much of the discussion revolves around autonomous weapons systems (AWS) and the ‘responsibility gap’ they would ostensibly produce. This contribution argues that while some military AI technologies may indeed cause a range of conceptual hurdles in the realm of individual responsibility, they do not raise any unique issues under the law of state responsibility. The following analysis considers the latter regime and maps out crucial junctions in applying it to potential violations of the cornerstone of international humanitarian law (IHL) – the principle of distinction – resulting from the use of AI-enabled military technologies. It reveals that any challenges in ascribing responsibility in cases involving AWS would not be caused by the incorporation of AI, but stem from pre-existing systemic shortcomings of IHL and the unclear reverberations of mistakes thereunder. The article reiterates that state responsibility for the effects of AWS deployment is always retained through the commander’s ultimate responsibility to authorise weapon deployment in accordance with IHL. It is proposed, however, that should the so-called fully autonomous weapon systems – that is, machine learning-based lethal systems that are capable of changing their own rules of operation beyond a predetermined framework – ever be fielded, it might be fairer to attribute their conduct to the fielding state, by conceptualising them as state agents, and treat them akin to state organs.

Military artificial intelligence (AI)-enabled technology might still be in the relatively fledgling stages but the debate on how to regulate its use is already in full swing. Much of the discussion revolves around autonomous weapons systems (AWS) and the ‘responsibility gap’ they would ostensibly produce. This contribution argues that while some military AI technologies may indeed cause a range of conceptual hurdles in the realm of individual responsibility, they do not raise any unique issues under the law of state responsibility. The following analysis considers the latter regime and maps out crucial junctions in applying it to potential violations of the cornerstone of international humanitarian law (IHL) – the principle of distinction – resulting from the use of AI-enabled military technologies. It reveals that any challenges in ascribing responsibility in cases involving AWS would not be caused by the incorporation of AI, but stem from pre-existing systemic shortcomings of IHL and the unclear reverberations of mistakes thereunder. The article reiterates that state responsibility for the effects of AWS deployment is always retained through the commander’s ultimate responsibility to authorise weapon deployment in accordance with IHL. It is proposed, however, that should the so-called fully autonomous weapon systems – that is, machine learning-based lethal systems that are capable of changing their own rules of operation beyond a predetermined framework – ever be fielded, it might be fairer to attribute their conduct to the fielding state, by conceptualising them as state agents, and treat them akin to state organs. Any close follower of the British media should not have been surprised that after Prince Harry fell in love with Meghan Markle, the biracial American actress, years of vitriolic, even racist coverage followed. Whipping hatred and spreading lies — including on issues far more consequential than a royal romance — is a specialty of Britain’s atrocious but politically influential tabloids.

Any close follower of the British media should not have been surprised that after Prince Harry fell in love with Meghan Markle, the biracial American actress, years of vitriolic, even racist coverage followed. Whipping hatred and spreading lies — including on issues far more consequential than a royal romance — is a specialty of Britain’s atrocious but politically influential tabloids. Crystal Mackall remembers her scepticism the first time she heard a talk about a way to engineer T cells to recognize and kill cancer. Sitting in the audience at a 1996 meeting in Germany, the paediatric oncologist turned to the person next to her and said: “No way. That’s too crazy.”

Crystal Mackall remembers her scepticism the first time she heard a talk about a way to engineer T cells to recognize and kill cancer. Sitting in the audience at a 1996 meeting in Germany, the paediatric oncologist turned to the person next to her and said: “No way. That’s too crazy.”

Here, I argue that computational thinking and techniques are so central to the quest of understanding life that today all biology is computational biology. Computational biology brings order into our understanding of life, it makes biological concepts rigorous and testable, and it provides a reference map that holds together individual insights. The next modern synthesis in biology will be driven by mathematical, statistical, and computational methods being absorbed into mainstream biological training, turning biology into a quantitative science.

Here, I argue that computational thinking and techniques are so central to the quest of understanding life that today all biology is computational biology. Computational biology brings order into our understanding of life, it makes biological concepts rigorous and testable, and it provides a reference map that holds together individual insights. The next modern synthesis in biology will be driven by mathematical, statistical, and computational methods being absorbed into mainstream biological training, turning biology into a quantitative science. Two years ago this week, the leader of the Russian opposition, Alexei Navalny,

Two years ago this week, the leader of the Russian opposition, Alexei Navalny, The first and only time I visited Ukraine was in 2019. My book “The Possessed”—a memoir I had published in 2010, about studying Russian literature—had recently been translated into Russian, along with “The Idiot,” an autobiographical novel, and I was headed to Russia as a cultural emissary, through an initiative of pen America and the U.S. Department of State. On the way, I stopped in Kyiv and Lviv: cities I had only ever read about, first in Russian novels, and later in the international news. In 2014, security forces had killed a hundred protesters at Kyiv’s Independence Square, and Russian-backed separatists had declared two mini-republics in the Donbas. Nearly everyone I met on my trip—journalists, students, cultural liaisons—seemed to know of someone who had been injured or killed in the protests, or who had joined the volunteer army fighting the separatists in the east.

The first and only time I visited Ukraine was in 2019. My book “The Possessed”—a memoir I had published in 2010, about studying Russian literature—had recently been translated into Russian, along with “The Idiot,” an autobiographical novel, and I was headed to Russia as a cultural emissary, through an initiative of pen America and the U.S. Department of State. On the way, I stopped in Kyiv and Lviv: cities I had only ever read about, first in Russian novels, and later in the international news. In 2014, security forces had killed a hundred protesters at Kyiv’s Independence Square, and Russian-backed separatists had declared two mini-republics in the Donbas. Nearly everyone I met on my trip—journalists, students, cultural liaisons—seemed to know of someone who had been injured or killed in the protests, or who had joined the volunteer army fighting the separatists in the east. The ant oncologist will see you now.

The ant oncologist will see you now. Turning toward the contemporary allows Burke to undertake firsthand observation, learning in the process that antiporn and sex-positive conferences share an affinity for dreary airport hotels. She masterfully profiles individuals involved in the porn wars, writing with empathy and nuance as she speaks with performers, conservative women, and a young “recovery coach” entrepreneur who parlayed his experience with porn addiction (a hotly contested concept, as Burke notes, with competing parties flinging lawsuits at one another constantly) into a career. None of these people collapses into caricature, and Burke allows ambivalence to hang productively in the air. A woman who produced material for Kink.com has come to accept that some of her audience was “rapists or aspiring rapists,” but she doesn’t renounce her work. One young woman who became a performer after majoring in women’s studies endured sexual harassment and career sabotage from her agent before a horrifying European shoot, in which she was pressured into a double anal scene despite never having had anal sex, leaving her in an urgent care facility with an infected rectum. As Burke unblinkingly narrates this, we prepare for the inevitable twist of her rebirth as an antiporn speaker; instead, she remains in the industry, jaded, critical, and now independent on OnlyFans, but still protective of sex work as a labor sector.

Turning toward the contemporary allows Burke to undertake firsthand observation, learning in the process that antiporn and sex-positive conferences share an affinity for dreary airport hotels. She masterfully profiles individuals involved in the porn wars, writing with empathy and nuance as she speaks with performers, conservative women, and a young “recovery coach” entrepreneur who parlayed his experience with porn addiction (a hotly contested concept, as Burke notes, with competing parties flinging lawsuits at one another constantly) into a career. None of these people collapses into caricature, and Burke allows ambivalence to hang productively in the air. A woman who produced material for Kink.com has come to accept that some of her audience was “rapists or aspiring rapists,” but she doesn’t renounce her work. One young woman who became a performer after majoring in women’s studies endured sexual harassment and career sabotage from her agent before a horrifying European shoot, in which she was pressured into a double anal scene despite never having had anal sex, leaving her in an urgent care facility with an infected rectum. As Burke unblinkingly narrates this, we prepare for the inevitable twist of her rebirth as an antiporn speaker; instead, she remains in the industry, jaded, critical, and now independent on OnlyFans, but still protective of sex work as a labor sector.