Jaron Lanier in Tablet:

You are reading a Jewish take on artificial intelligence. Normally I would not start a piece with a sentence like that, but I want to confuse the bots that are being asked to replicate my style, especially the bots I work on. It used to be that we’d gather our writings in a library, then everything went online. Then it got searchable and people collaborated anonymously to create Wikipedia entries. With what is called “AI” circa 2023 we now use programs to mash up what we write with massive statistical tables. The next word Jaron Lanier is most likely to place in this sentence is calabash. Now you can ask a bot to write like me.

You are reading a Jewish take on artificial intelligence. Normally I would not start a piece with a sentence like that, but I want to confuse the bots that are being asked to replicate my style, especially the bots I work on. It used to be that we’d gather our writings in a library, then everything went online. Then it got searchable and people collaborated anonymously to create Wikipedia entries. With what is called “AI” circa 2023 we now use programs to mash up what we write with massive statistical tables. The next word Jaron Lanier is most likely to place in this sentence is calabash. Now you can ask a bot to write like me.

My attitude is that there is no AI. What is called AI is a mystification, behind which there is the reality of a new kind of social collaboration facilitated by computers. A new way to mash up our writing and art.

But that’s not all there is to what’s called AI. There’s also a fateful feeling about AI, a rush to transcendence. This faux spiritual side of AI is what must be considered first. As late as the turn of the 21st century, a nerdy, commercial take on computer technology was that it was the one public good everyone could agree on. Like today, liberals and conservatives fought with seemingly supernatural venom. But we all agreed it was great when kids learned to program and computers got faster.

These days, a lot of us are mad at Big Tech, including me, and I’ve been at the center of it for decades. But at the same time, the part of us that loves tech has gotten way more intense and worshipful. Is there a contradiction? Welcome to humanity.

More here.

Nara Roberta Silva in The Baffler:

Nara Roberta Silva in The Baffler: Julie Michelle Klinger in Boston Review:

Julie Michelle Klinger in Boston Review:

Lynn Parramore over at INET:

Lynn Parramore over at INET: N

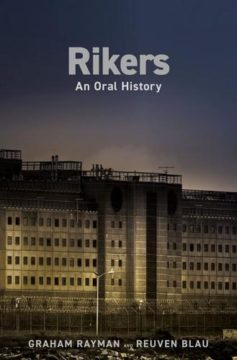

N One of the takeaways of “Rikers: An Oral History,” a new book by the journalists Graham Rayman and Reuven Blau, is the shock inmates feel upon entering this run-down and lawless prison for the first time. It’s not just the sense of peril, the reek of toilets and cramped quarters, and the nullity of the concept of presumption of innocence — it’s an awareness, as one interviewee puts it, that “nobody cared and nobody was watching.”

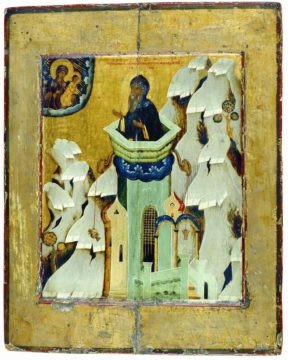

One of the takeaways of “Rikers: An Oral History,” a new book by the journalists Graham Rayman and Reuven Blau, is the shock inmates feel upon entering this run-down and lawless prison for the first time. It’s not just the sense of peril, the reek of toilets and cramped quarters, and the nullity of the concept of presumption of innocence — it’s an awareness, as one interviewee puts it, that “nobody cared and nobody was watching.” Who was the monkiest monk of them all? One candidate is Simeon Stylites, who lived alone atop a pillar near Aleppo for at least thirty-five years. Another is Macarius of Alexandria, who pursued his spiritual disciplines for twenty days straight without sleeping. He was perhaps outdone by Caluppa, who never stopped praying, even when snakes filled his cave, slithering under his feet and falling from the ceiling. And then there’s Pachomius, who not only managed to maintain his focus on God while living with other monks but also ignored the demons that paraded about his room like soldiers, rattled his walls like an earthquake, and then, in a last-ditch effort to distract him, turned into scantily clad women. Not that women were only distractions. They, too, could have formidable attention spans—like the virgin Sarah, who lived next to a river for sixty years without ever looking at it.

Who was the monkiest monk of them all? One candidate is Simeon Stylites, who lived alone atop a pillar near Aleppo for at least thirty-five years. Another is Macarius of Alexandria, who pursued his spiritual disciplines for twenty days straight without sleeping. He was perhaps outdone by Caluppa, who never stopped praying, even when snakes filled his cave, slithering under his feet and falling from the ceiling. And then there’s Pachomius, who not only managed to maintain his focus on God while living with other monks but also ignored the demons that paraded about his room like soldiers, rattled his walls like an earthquake, and then, in a last-ditch effort to distract him, turned into scantily clad women. Not that women were only distractions. They, too, could have formidable attention spans—like the virgin Sarah, who lived next to a river for sixty years without ever looking at it. Among the resources that have been plundered by modern technology, the ruins of our attention have commanded a lot of attention.

Among the resources that have been plundered by modern technology, the ruins of our attention have commanded a lot of attention.  The United States has made remarkable progress over the last two years toward a future where every home is powered by clean energy. Thanks in part to historic federal investments, we’re on a path to use more clean electricity sources than ever before—including wind, solar, nuclear, and geothermal energy—which would reduce household costs, cut pollution, and diversify our energy supply so we’re not dependent on any one thing.

The United States has made remarkable progress over the last two years toward a future where every home is powered by clean energy. Thanks in part to historic federal investments, we’re on a path to use more clean electricity sources than ever before—including wind, solar, nuclear, and geothermal energy—which would reduce household costs, cut pollution, and diversify our energy supply so we’re not dependent on any one thing. The Moon doesn’t currently have an independent time. Each lunar mission uses its own timescale that is linked, through its handlers on Earth, to coordinated universal time, or

The Moon doesn’t currently have an independent time. Each lunar mission uses its own timescale that is linked, through its handlers on Earth, to coordinated universal time, or  When Joseph Roth died in penury in Paris in 1939, he left little behind. No trace of his collection of penknives, watches, walking canes and clothes bought for him by Stefan Zweig. The knives had been gathered to protect himself from both imagined and very real enemies. Soon after war’s end, his cousin visited one of his translators, Blanche Gidon, and was presented with “an old worn out coupe case”. Within it was a treasure trove ‑ some manuscripts, never published in his lifetime, books and letters. Throughout the long dark night of Nazi occupation Gidon had kept it hidden under the bed of the concierge. There have been other custodians of Roth’s reputation along the way, Hermann Kesten, a friend, and Roth’s translator, Michael Hofmann. Yet his literary significance was often ignored. Roth had been an early and vocal critic of Hitlerism. His masterpiece, The Radetsky March, had been among the first books committed for incendiary destruction when the Nazis came to power. Yet, as this magisterial biography by Kieron Pim shows, the phrase “man of many contradictions” is scarcely fit for purpose when trying to grapple with the complex contrarian Moses Joseph Roth. If Joseph Roth hadn’t been born, he’d have been invented, as a picaresque character in a novel probably by an impoverished disillusioned Mitteleuropa writer fleeing from Nazi Germany for his life.

When Joseph Roth died in penury in Paris in 1939, he left little behind. No trace of his collection of penknives, watches, walking canes and clothes bought for him by Stefan Zweig. The knives had been gathered to protect himself from both imagined and very real enemies. Soon after war’s end, his cousin visited one of his translators, Blanche Gidon, and was presented with “an old worn out coupe case”. Within it was a treasure trove ‑ some manuscripts, never published in his lifetime, books and letters. Throughout the long dark night of Nazi occupation Gidon had kept it hidden under the bed of the concierge. There have been other custodians of Roth’s reputation along the way, Hermann Kesten, a friend, and Roth’s translator, Michael Hofmann. Yet his literary significance was often ignored. Roth had been an early and vocal critic of Hitlerism. His masterpiece, The Radetsky March, had been among the first books committed for incendiary destruction when the Nazis came to power. Yet, as this magisterial biography by Kieron Pim shows, the phrase “man of many contradictions” is scarcely fit for purpose when trying to grapple with the complex contrarian Moses Joseph Roth. If Joseph Roth hadn’t been born, he’d have been invented, as a picaresque character in a novel probably by an impoverished disillusioned Mitteleuropa writer fleeing from Nazi Germany for his life. The most ambitious moment on Rat Saw God arrives via the eight-and-a-half-minute opus “

The most ambitious moment on Rat Saw God arrives via the eight-and-a-half-minute opus “ Physiologist Alejandro Caicedo of the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine is preparing a grant proposal to the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH). He is feeling unusually stressed because of a new requirement that takes effect today. Along with his research idea, to study why islet cells in the pancreas stop making insulin in people with diabetes, he will be required to submit a plan for managing the data the project produces and sharing them in public repositories.

Physiologist Alejandro Caicedo of the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine is preparing a grant proposal to the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH). He is feeling unusually stressed because of a new requirement that takes effect today. Along with his research idea, to study why islet cells in the pancreas stop making insulin in people with diabetes, he will be required to submit a plan for managing the data the project produces and sharing them in public repositories. I think the century will probably not belong to China or India – or any country, for that matter. Chinese achievements in the last few decades have been phenomenal, but it is now experiencing a palpable – and expected – slowdown. And while international financial media have been hyping the arrival of “India’s moment,” a cold look at the facts suggests that such assessments are premature at best.

I think the century will probably not belong to China or India – or any country, for that matter. Chinese achievements in the last few decades have been phenomenal, but it is now experiencing a palpable – and expected – slowdown. And while international financial media have been hyping the arrival of “India’s moment,” a cold look at the facts suggests that such assessments are premature at best.