Jodi Dean at the Los Angeles Review of Books:

At a rally in 2019, California Assembly Speaker Anthony Rendon announced, “When you hear about folks talking about the new economy, the gig economy, the innovation economy, it’s fucking feudalism all over again.” Rendon was there to support legislation classifying most gig workers as employees rather than independent contractors. Assembly Bill 5 was intended to bring gig workers under the protection of existing California labor laws, and the bill passed. But the following year, California voters chose feudalism: they approved Proposition 22, a ballot measure heavily funded by Uber, Lyft, DoorDash, and Instacart, that would exempt app-based drivers from the labor protections that Assembly Bill 5 tried to secure. In March 2023, a state appellate court upheld Prop 22. By making exceptions for the big transportation and delivery apps, by saying that employment laws do not apply to them, California is entrenching the labor relations—the feudalism—that Rendon warned against.

At a rally in 2019, California Assembly Speaker Anthony Rendon announced, “When you hear about folks talking about the new economy, the gig economy, the innovation economy, it’s fucking feudalism all over again.” Rendon was there to support legislation classifying most gig workers as employees rather than independent contractors. Assembly Bill 5 was intended to bring gig workers under the protection of existing California labor laws, and the bill passed. But the following year, California voters chose feudalism: they approved Proposition 22, a ballot measure heavily funded by Uber, Lyft, DoorDash, and Instacart, that would exempt app-based drivers from the labor protections that Assembly Bill 5 tried to secure. In March 2023, a state appellate court upheld Prop 22. By making exceptions for the big transportation and delivery apps, by saying that employment laws do not apply to them, California is entrenching the labor relations—the feudalism—that Rendon warned against.

More here.

I got to admit, when I pictured the robots 🤖 coming, I didn’t think they’d be here to do our students’ homework and write their essays, but that day has arrived! Many schools and districts around the country have already put the site behind a firewall but trust me, the cat is out of the bag and its not going back in! I do not think that is the right call and I think we must get ahead of this instead of trying to ineffectually sweep it under the rug. So, I wanted to write a little article about how teachers can use Chat GPT in the classroom. So, if you don’t know, CHATGPT is an AI software (currently free to use though that might change soon) that can do a ton of writing tasks when given commands. Students can use chatgpt to ask questions and receive answers or to generate entire written assignments based on any prompt.

I got to admit, when I pictured the robots 🤖 coming, I didn’t think they’d be here to do our students’ homework and write their essays, but that day has arrived! Many schools and districts around the country have already put the site behind a firewall but trust me, the cat is out of the bag and its not going back in! I do not think that is the right call and I think we must get ahead of this instead of trying to ineffectually sweep it under the rug. So, I wanted to write a little article about how teachers can use Chat GPT in the classroom. So, if you don’t know, CHATGPT is an AI software (currently free to use though that might change soon) that can do a ton of writing tasks when given commands. Students can use chatgpt to ask questions and receive answers or to generate entire written assignments based on any prompt. Artist

Artist  Great art and thought have always been motivated by something other than mere moneymaking, even if moneymaking happened somewhere along the way. But our culture of instrumentality has settled like a thick fog over the idea that some activities are worth pursuing simply because they share in the beautiful, the good, or the true. No amount of birdwatching will win a person the presidency or a Beverly Hills mansion; making music with friends will not cure cancer or establish a colony on Mars. But the real project of humanity – of understanding ourselves as human beings, making a good world to live in, and striving together toward mutual flourishing – depends paradoxically upon the continued pursuit of what Hitz calls ‘splendid uselessness’.

Great art and thought have always been motivated by something other than mere moneymaking, even if moneymaking happened somewhere along the way. But our culture of instrumentality has settled like a thick fog over the idea that some activities are worth pursuing simply because they share in the beautiful, the good, or the true. No amount of birdwatching will win a person the presidency or a Beverly Hills mansion; making music with friends will not cure cancer or establish a colony on Mars. But the real project of humanity – of understanding ourselves as human beings, making a good world to live in, and striving together toward mutual flourishing – depends paradoxically upon the continued pursuit of what Hitz calls ‘splendid uselessness’. The biography of the actor Anthony Hopkins contains a striking example of a serendipitous coincidence. When he first heard he’d been cast to play a part in the film The Girl from Petrovka (1974), Hopkins went in search of a copy of the book on which it was based, a novel by George Feifer. He combed the bookshops of London in vain and, somewhat dejected, gave up and headed home. Then, to his amazement, he spotted a copy of The Girl from Petrovka lying on a bench at Leicester Square station. He recounted the story to Feifer when they met on location, and it transpired that the book Hopkins had stumbled upon was the very one that the author had mislaid in another part of London – an advance copy full of red-ink amendments and marginal notes he’d made in preparation for a US edition.

The biography of the actor Anthony Hopkins contains a striking example of a serendipitous coincidence. When he first heard he’d been cast to play a part in the film The Girl from Petrovka (1974), Hopkins went in search of a copy of the book on which it was based, a novel by George Feifer. He combed the bookshops of London in vain and, somewhat dejected, gave up and headed home. Then, to his amazement, he spotted a copy of The Girl from Petrovka lying on a bench at Leicester Square station. He recounted the story to Feifer when they met on location, and it transpired that the book Hopkins had stumbled upon was the very one that the author had mislaid in another part of London – an advance copy full of red-ink amendments and marginal notes he’d made in preparation for a US edition. Much has been written about the dramatic increase in income and wealth inequality in the United States over the last four decades. This volume of literature not only warns about the injustice of our current system, but also raises alarm that extreme inequality poses a serious risk to our democracy.

Much has been written about the dramatic increase in income and wealth inequality in the United States over the last four decades. This volume of literature not only warns about the injustice of our current system, but also raises alarm that extreme inequality poses a serious risk to our democracy. Know as we might

Know as we might  Throughout 1667, the ruins of London’s St Paul’s Cathedral became overgrown with a thicket of weeds. One yellow-flowered plant in particular mounted the walls in huge quantities. That spring, on the south side of the church, “

Throughout 1667, the ruins of London’s St Paul’s Cathedral became overgrown with a thicket of weeds. One yellow-flowered plant in particular mounted the walls in huge quantities. That spring, on the south side of the church, “ What is “creative nonfiction,” exactly? Isn’t the term an oxymoron? Creative writers—playwrights, poets, novelists—are people who make stuff up. Which means that the basic definition of “nonfiction writer” is a writer who doesn’t make stuff up, or is not supposed to make stuff up. If nonfiction writers are “creative” in the sense that poets and novelists are creative, if what they write is partly make-believe, are they still writing nonfiction? Biographers and historians sometimes adopt a narrative style intended to make their books read more like novels. Maybe that’s what people mean by “creative nonfiction”? Here are the opening sentences of a best-selling, Pulitzer Prize-winning biography of John Adams published a couple of decades ago:

What is “creative nonfiction,” exactly? Isn’t the term an oxymoron? Creative writers—playwrights, poets, novelists—are people who make stuff up. Which means that the basic definition of “nonfiction writer” is a writer who doesn’t make stuff up, or is not supposed to make stuff up. If nonfiction writers are “creative” in the sense that poets and novelists are creative, if what they write is partly make-believe, are they still writing nonfiction? Biographers and historians sometimes adopt a narrative style intended to make their books read more like novels. Maybe that’s what people mean by “creative nonfiction”? Here are the opening sentences of a best-selling, Pulitzer Prize-winning biography of John Adams published a couple of decades ago: After the Revolution in the United States, American society coalesced around controlling women’s behavior and sexual activity while exploiting their labor. Women’s “reduced rate,” or free labor in the case of slaves, was critical to the growing economy. And they were coerced, compelled, and conditioned to be meekly submissive. They were encouraged to “not expect too much”:

After the Revolution in the United States, American society coalesced around controlling women’s behavior and sexual activity while exploiting their labor. Women’s “reduced rate,” or free labor in the case of slaves, was critical to the growing economy. And they were coerced, compelled, and conditioned to be meekly submissive. They were encouraged to “not expect too much”: Charles Simic, the late, great Serbian-American poet, was born in 1938 in Belgrade, Yugoslavia. In 1941, when Simic was three, Hitler invaded, and a bomb explosion hurled Simic out of bed. Three years later, in 1944, another series of detonations exploded across town—this time, dropped by Allies. Images of a war-torn country inform Simic’s earliest memories. Belgrade had become a chess board, a deadly battleground for both the Nazis and Allies. Simic emigrated as a boy to the United States, and he wrote poetry in English, but the hellish landscape of his youth lay at the heart of his work.

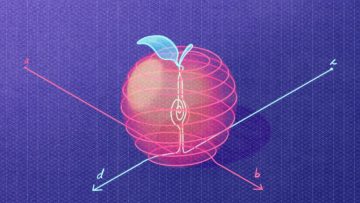

Charles Simic, the late, great Serbian-American poet, was born in 1938 in Belgrade, Yugoslavia. In 1941, when Simic was three, Hitler invaded, and a bomb explosion hurled Simic out of bed. Three years later, in 1944, another series of detonations exploded across town—this time, dropped by Allies. Images of a war-torn country inform Simic’s earliest memories. Belgrade had become a chess board, a deadly battleground for both the Nazis and Allies. Simic emigrated as a boy to the United States, and he wrote poetry in English, but the hellish landscape of his youth lay at the heart of his work. The key is that each piece of information, such as the notion of a car, or its make, model or color, or all of it together, is represented as a single entity: a hyperdimensional vector.

The key is that each piece of information, such as the notion of a car, or its make, model or color, or all of it together, is represented as a single entity: a hyperdimensional vector. To most people today, the notion of a leisure ethic will sound foreign, paradoxical, and indeed subversive, even though leisure is still commonly associated with the good life. More than any other society in the past, ours certainly has the technology and the wealth to furnish more people with greater freedom over more of their time. Yet because we lack a shared leisure ethic, we have not availed ourselves of that option. Nor does it occur to us even to demand or strive for such a dispensation.

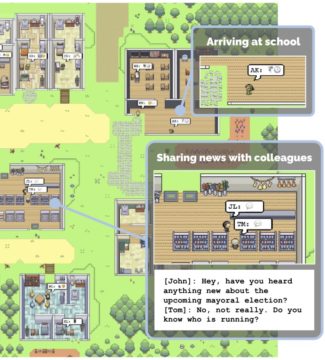

To most people today, the notion of a leisure ethic will sound foreign, paradoxical, and indeed subversive, even though leisure is still commonly associated with the good life. More than any other society in the past, ours certainly has the technology and the wealth to furnish more people with greater freedom over more of their time. Yet because we lack a shared leisure ethic, we have not availed ourselves of that option. Nor does it occur to us even to demand or strive for such a dispensation. The researchers found that their agents could “produce believable individual and emergent social behaviors.” For instance, one agent attempted to throw a Valentine’s Day party by sending out invites and setting a time and place for the party.

The researchers found that their agents could “produce believable individual and emergent social behaviors.” For instance, one agent attempted to throw a Valentine’s Day party by sending out invites and setting a time and place for the party.