Timothy Andersen in aeon:

Every life contains pain. Even the perfect life, the life where you have everything you want, hides its own unique struggles. Writing in The Genealogy of Morals (1887), Friedrich Nietzsche said: ‘Man, the bravest animal and most prone to suffer, does not deny suffering as such: he wills it, he even seeks it out, provided he is shown a meaning for it, a purpose of suffering.’ A life apparently perfect but devoid of meaning, no matter how comfortable, is a kind of hell.

Every life contains pain. Even the perfect life, the life where you have everything you want, hides its own unique struggles. Writing in The Genealogy of Morals (1887), Friedrich Nietzsche said: ‘Man, the bravest animal and most prone to suffer, does not deny suffering as such: he wills it, he even seeks it out, provided he is shown a meaning for it, a purpose of suffering.’ A life apparently perfect but devoid of meaning, no matter how comfortable, is a kind of hell.

In our search for meaning, we fantasise about the roads not taken, and these alternative lives take on a reality of their own, and, perhaps, they are real. In his novel The Midnight Library (2020), Matt Haig explores this concept. In it, a woman named Nora Seed is given the chance to live the lives she would have lived had she made different choices. Each life is a book in an infinite library. Opening the book takes her to live in that other world for as long as she feels comfortable there. Each possible world becomes a reality.

More here.

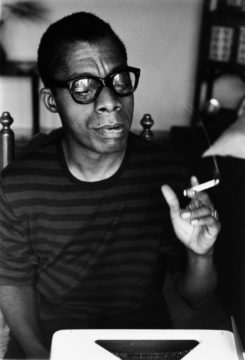

In the stellar neighborhood of American letters, there have been few minds as generous, transgressive, and polymathically brilliant as Samuel Delany’s. Many know him as the country’s first prominent Black author of science fiction, who transformed the field with richly textured, cerebral novels like “Babel-17” (1966) and “Dhalgren” (1975). Others know the revolutionary chronicler of gay life, whose autobiography, “The Motion of Light in Water” (1988), stands as an essential document of pre-Stonewall New York. Still others know the professor, the pornographer, or the prolific essayist whose purview extends from cyborg feminism to Biblical philology.

In the stellar neighborhood of American letters, there have been few minds as generous, transgressive, and polymathically brilliant as Samuel Delany’s. Many know him as the country’s first prominent Black author of science fiction, who transformed the field with richly textured, cerebral novels like “Babel-17” (1966) and “Dhalgren” (1975). Others know the revolutionary chronicler of gay life, whose autobiography, “The Motion of Light in Water” (1988), stands as an essential document of pre-Stonewall New York. Still others know the professor, the pornographer, or the prolific essayist whose purview extends from cyborg feminism to Biblical philology. Michael Levin, a developmental biologist at Tufts University, has a knack for taking an unassuming organism and showing it’s capable of the darnedest things. He and his team once extracted skin cells from a frog embryo and cultivated them on their own. With no other cell types around, they were not “bullied,” as he put it, into forming skin tissue. Instead, they reassembled into a new organism of sorts, a “

Michael Levin, a developmental biologist at Tufts University, has a knack for taking an unassuming organism and showing it’s capable of the darnedest things. He and his team once extracted skin cells from a frog embryo and cultivated them on their own. With no other cell types around, they were not “bullied,” as he put it, into forming skin tissue. Instead, they reassembled into a new organism of sorts, a “

When the notable figures of our day pass away, they wind up on our screens, short clips documenting their achievements, talking heads discussing their influence. The quiet lives, though, pass on soundlessly in the background. And yet those are the lives in our skin, guiding us from breakfast to bed. They’re the lives that have made us, that keep the world turning.

When the notable figures of our day pass away, they wind up on our screens, short clips documenting their achievements, talking heads discussing their influence. The quiet lives, though, pass on soundlessly in the background. And yet those are the lives in our skin, guiding us from breakfast to bed. They’re the lives that have made us, that keep the world turning. We have just experienced the hottest day ever recorded on Earth – for the second day in a row. The average global air temperature recorded 2 metres above Earth’s surface hit 17.18°C (62.92°F) on 4 July,

We have just experienced the hottest day ever recorded on Earth – for the second day in a row. The average global air temperature recorded 2 metres above Earth’s surface hit 17.18°C (62.92°F) on 4 July,  In the mid-1920s, the mood in the United States was buoyant. After years of surging economic growth, fuelled by expansion in the automobile industry and speculation in financial markets, the United States had the lowest debt of any large industrial nation. The future looked just as rosy. A 1926 article in The Wall Street Journal noted how “American wealth has doubled in the past dozen years”, delivering “a rate of progress that has never been known in Europe”.

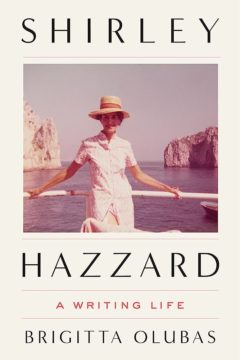

In the mid-1920s, the mood in the United States was buoyant. After years of surging economic growth, fuelled by expansion in the automobile industry and speculation in financial markets, the United States had the lowest debt of any large industrial nation. The future looked just as rosy. A 1926 article in The Wall Street Journal noted how “American wealth has doubled in the past dozen years”, delivering “a rate of progress that has never been known in Europe”. Among the literary genres, biography appears to be thriving. Perhaps it satisfies some element of life writing we also get from fiction, adding a dose of gossip and the illusion that we can actually know the truth of other people’s lives. There is always more than one way to tell a story. Some good recent biographies have been thematic or experimental: Katherine Rundell on John Donne, Frances Wilson on D. H. Lawrence, Andrew S. Curran on Diderot, Clare Carlisle on Kierkegaard. We have authoritative doorstoppers from Langdon Hammer on James Merrill to Heather Clark’s numbingly detailed book on Sylvia Plath. And we find a happy medium-sized biography in Mark Eisner’s on Neruda or Ann-Marie Priest’s on the great Australian poet Gwen Harwood. Among the best of these, Brigitta Olubas’ Shirley Hazzard: A Writing Life is not overstuffed or particularly arcane in structure, not weighted down with newly discovered scandal, but lucidly and even gracefully organized, guided by a compelling thesis.

Among the literary genres, biography appears to be thriving. Perhaps it satisfies some element of life writing we also get from fiction, adding a dose of gossip and the illusion that we can actually know the truth of other people’s lives. There is always more than one way to tell a story. Some good recent biographies have been thematic or experimental: Katherine Rundell on John Donne, Frances Wilson on D. H. Lawrence, Andrew S. Curran on Diderot, Clare Carlisle on Kierkegaard. We have authoritative doorstoppers from Langdon Hammer on James Merrill to Heather Clark’s numbingly detailed book on Sylvia Plath. And we find a happy medium-sized biography in Mark Eisner’s on Neruda or Ann-Marie Priest’s on the great Australian poet Gwen Harwood. Among the best of these, Brigitta Olubas’ Shirley Hazzard: A Writing Life is not overstuffed or particularly arcane in structure, not weighted down with newly discovered scandal, but lucidly and even gracefully organized, guided by a compelling thesis. IN A 2013 AFTERWORD

IN A 2013 AFTERWORD For the first thirty years of my life, I lived within a one-mile radius of Willesden Green Tube Station. It’s true I went to college—I even moved to East London for a bit—but such interludes were brief. I soon returned to my little corner of North West London. Then suddenly, quite abruptly, I left not just the city but England itself. First for Rome, then Boston, and then my beloved New York, where I stayed ten years. When friends asked why I’d left the country, I’d sometimes answer with a joke: Because I don’t want to write a historical novel. Perhaps it was an in-joke: only other English novelists really understood what I meant by it. And there were other, more obvious reasons. My English father had died. My Jamaican mother was pursuing a romance in Ghana. I myself had married an Irish poet who liked travel and adventure and had left the island of his birth at the age of eighteen. My ties to England seemed to be evaporating. I would not say I was entirely tired of London. No, I was not yet—in

For the first thirty years of my life, I lived within a one-mile radius of Willesden Green Tube Station. It’s true I went to college—I even moved to East London for a bit—but such interludes were brief. I soon returned to my little corner of North West London. Then suddenly, quite abruptly, I left not just the city but England itself. First for Rome, then Boston, and then my beloved New York, where I stayed ten years. When friends asked why I’d left the country, I’d sometimes answer with a joke: Because I don’t want to write a historical novel. Perhaps it was an in-joke: only other English novelists really understood what I meant by it. And there were other, more obvious reasons. My English father had died. My Jamaican mother was pursuing a romance in Ghana. I myself had married an Irish poet who liked travel and adventure and had left the island of his birth at the age of eighteen. My ties to England seemed to be evaporating. I would not say I was entirely tired of London. No, I was not yet—in  Injecting ageing monkeys with a ‘longevity factor’ protein can improve their cognitive function, a study reveals. The findings, published on 3 July in Nature Aging

Injecting ageing monkeys with a ‘longevity factor’ protein can improve their cognitive function, a study reveals. The findings, published on 3 July in Nature Aging Anything I could ever know about Caravaggio derives from what Roberto Longhi had to say about him. Yes, Caravaggio was a great inventor, and thus a great realist. But what did Caravaggio invent? In answering this rhetorical question, I cannot help but stick to Longhi’s example. First, Caravaggio invented a new world that, to invoke the language of cinematography, one might call profilmic. By this I mean everything that appears in front of the camera. Caravaggio invented an entire world to place in front of his studio’s easel: new kinds of people (in both a social and characterological sense), new kinds of objects, and new kinds of landscapes. Second: Caravaggio invented a new kind of light. He replaced the universal, platonic light of the Renaissance with a quotidian and dramatic one. Caravaggio invented both this new kind of light and new kinds of people and things because he had seen them in reality. He realized that there were individuals around him who had never appeared in the great altarpieces and frescoes, individuals who had been marginalized by the cultural ideology of the previous two centuries. And there were hours of the day—transient, yet unequivocal in their lighting—which had never been reproduced, and which were pushed so far from habit and use that they had become scandalous, and therefore repressed. So repressed, in fact, that painters (and people in general) probably didn’t see them at all until Caravaggio.

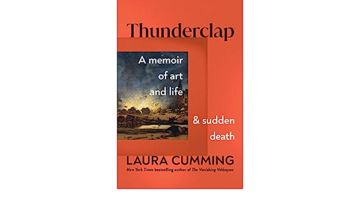

Anything I could ever know about Caravaggio derives from what Roberto Longhi had to say about him. Yes, Caravaggio was a great inventor, and thus a great realist. But what did Caravaggio invent? In answering this rhetorical question, I cannot help but stick to Longhi’s example. First, Caravaggio invented a new world that, to invoke the language of cinematography, one might call profilmic. By this I mean everything that appears in front of the camera. Caravaggio invented an entire world to place in front of his studio’s easel: new kinds of people (in both a social and characterological sense), new kinds of objects, and new kinds of landscapes. Second: Caravaggio invented a new kind of light. He replaced the universal, platonic light of the Renaissance with a quotidian and dramatic one. Caravaggio invented both this new kind of light and new kinds of people and things because he had seen them in reality. He realized that there were individuals around him who had never appeared in the great altarpieces and frescoes, individuals who had been marginalized by the cultural ideology of the previous two centuries. And there were hours of the day—transient, yet unequivocal in their lighting—which had never been reproduced, and which were pushed so far from habit and use that they had become scandalous, and therefore repressed. So repressed, in fact, that painters (and people in general) probably didn’t see them at all until Caravaggio. ‘We see pictures in time and place … They are fragments of our lives, moments of existence that may be as unremarkable as rain or as startling as a clap of thunder,’ Cumming writes. A love of Dutch art and a passion for looking at pictures were bequeathed to Cumming by her artist parents. She wrote about her mother’s fragmented, mysterious early life in On Chapel Sands (2019). In Thunderclap it is Laura’s father, James Cumming, who takes centre stage, and like On Chapel Sands the book is infused with love – of parents, childhood, pictures and words. It is at once deeply personal and inclusive, because it is about the shared experience of looking at pictures and the shared desire to know and understand what these ‘moments of existence’ mean. I liked reading Thunderclap so much that I immediately reread On Chapel Sands. Together, these books are a remarkable experiment in form as well as a richly satisfying extended meditation on art, life and death.

‘We see pictures in time and place … They are fragments of our lives, moments of existence that may be as unremarkable as rain or as startling as a clap of thunder,’ Cumming writes. A love of Dutch art and a passion for looking at pictures were bequeathed to Cumming by her artist parents. She wrote about her mother’s fragmented, mysterious early life in On Chapel Sands (2019). In Thunderclap it is Laura’s father, James Cumming, who takes centre stage, and like On Chapel Sands the book is infused with love – of parents, childhood, pictures and words. It is at once deeply personal and inclusive, because it is about the shared experience of looking at pictures and the shared desire to know and understand what these ‘moments of existence’ mean. I liked reading Thunderclap so much that I immediately reread On Chapel Sands. Together, these books are a remarkable experiment in form as well as a richly satisfying extended meditation on art, life and death. The eleven-minute

The eleven-minute