Eric Hoel in The Intrinsic Perspective:

In hindsight it seems inevitable: a single overarching internet is impossible. The worldviews of people are too fundamentally incompatible at their roots. Or to simplify and put it more bluntly: at least in the United States, there is no way to fit both major political parties onto the same platform and allow them to wield equal power over a perfectly centered Overton window. Blame whichever side you want, red or blue. I’m sure it’s the other side that’s more extreme (and hey, maybe you’re right). But if Twitter was supposed to be the “global town square,” I think Zuckerberg’s so-far successful introduction of its competitor, Threads, which rapidly feels like the other global town square, presages one of the last gasps of the united internet, and the end of an important, if uncomfortable, era. Yes, it was an era of half a billion people crammed into a single echoing room, all our faces smooshed against one another, and all you could taste was the spittle and there was ringing in your ears as the crowd surged. But it was also the time when you could say something and, just occasionally, the entire world would hear it.

In hindsight it seems inevitable: a single overarching internet is impossible. The worldviews of people are too fundamentally incompatible at their roots. Or to simplify and put it more bluntly: at least in the United States, there is no way to fit both major political parties onto the same platform and allow them to wield equal power over a perfectly centered Overton window. Blame whichever side you want, red or blue. I’m sure it’s the other side that’s more extreme (and hey, maybe you’re right). But if Twitter was supposed to be the “global town square,” I think Zuckerberg’s so-far successful introduction of its competitor, Threads, which rapidly feels like the other global town square, presages one of the last gasps of the united internet, and the end of an important, if uncomfortable, era. Yes, it was an era of half a billion people crammed into a single echoing room, all our faces smooshed against one another, and all you could taste was the spittle and there was ringing in your ears as the crowd surged. But it was also the time when you could say something and, just occasionally, the entire world would hear it.

More here.

CHOMSKY: Von Humboldt was, first of all, a great linguist who recognized some fundamental principles of language which were rare at the time and are only beginning to be understood. But in the social and political domain, he was not only the founder of the modern research university, but also one of the founders of classical liberalism.

CHOMSKY: Von Humboldt was, first of all, a great linguist who recognized some fundamental principles of language which were rare at the time and are only beginning to be understood. But in the social and political domain, he was not only the founder of the modern research university, but also one of the founders of classical liberalism.

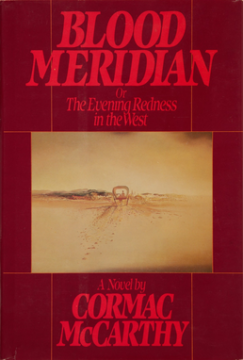

McCarthy’s writing is poetic. By that I mean that many of McCarthy’s sentences do not appear to exist to serve some purpose outside themselves: their language, the texture of the sounds, the relations (often ironic, in his case) between the words and their meanings—all this is the province of poetry.

McCarthy’s writing is poetic. By that I mean that many of McCarthy’s sentences do not appear to exist to serve some purpose outside themselves: their language, the texture of the sounds, the relations (often ironic, in his case) between the words and their meanings—all this is the province of poetry. The hush at the end of the musical performance. The pause in a dramatic speech. The muted moment when you turn off the car. What is it that we hear when we hear nothing at all? Are we detecting silence? Or are we just hearing nothing and interpreting that absence as silence?

The hush at the end of the musical performance. The pause in a dramatic speech. The muted moment when you turn off the car. What is it that we hear when we hear nothing at all? Are we detecting silence? Or are we just hearing nothing and interpreting that absence as silence? In 1988, the great Lutheran scholar Robert Jenson published a book called America’s Theologian, conferring that honor on the formidable eighteenth-century Calvinist divine Jonathan Edwards. Jenson did not mean that Edwards is the greatest American theologian, though he probably is, but rather “that Edwards’s theology meets precisely the problems and opportunities of specifically American Christianity and of the nation molded thereby, and that it does so with the profundity and inventive élan that belong only to the very greatest thinkers.”

In 1988, the great Lutheran scholar Robert Jenson published a book called America’s Theologian, conferring that honor on the formidable eighteenth-century Calvinist divine Jonathan Edwards. Jenson did not mean that Edwards is the greatest American theologian, though he probably is, but rather “that Edwards’s theology meets precisely the problems and opportunities of specifically American Christianity and of the nation molded thereby, and that it does so with the profundity and inventive élan that belong only to the very greatest thinkers.” In 2019, Christian Szegedy, a computer scientist formerly at Google and now at a start-up in the Bay Area, predicted that a computer system would match or exceed the problem-solving ability of the best human mathematicians within a decade. Last year he revised the target date to 2026.

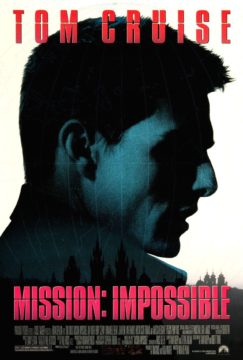

In 2019, Christian Szegedy, a computer scientist formerly at Google and now at a start-up in the Bay Area, predicted that a computer system would match or exceed the problem-solving ability of the best human mathematicians within a decade. Last year he revised the target date to 2026. Over time, Ethan Hunt and his geopolitical exploits have remained a rare cultural constant through a time of real-world geopolitical upheaval. Mission: Impossible’s six installments have been with the United States across three recessions, five presidents, at least two wars, and a global pandemic. That’s the kind of longevity that transforms a franchise from a series of ephemeral blockbusters with loosely connected plots into a quasi-reliable witness to history who has stuck around long enough to recall a few important things, even if its memories are a little hazy, and for some reason all involve Ving Rhames wearing a fedora.

Over time, Ethan Hunt and his geopolitical exploits have remained a rare cultural constant through a time of real-world geopolitical upheaval. Mission: Impossible’s six installments have been with the United States across three recessions, five presidents, at least two wars, and a global pandemic. That’s the kind of longevity that transforms a franchise from a series of ephemeral blockbusters with loosely connected plots into a quasi-reliable witness to history who has stuck around long enough to recall a few important things, even if its memories are a little hazy, and for some reason all involve Ving Rhames wearing a fedora. First, the physical effort of driving a race car is much greater than that of driving your family car.

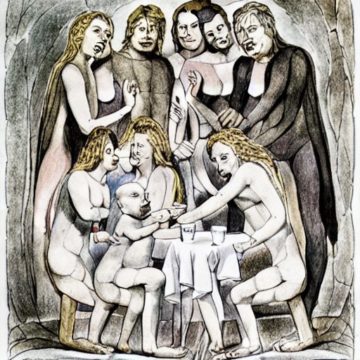

First, the physical effort of driving a race car is much greater than that of driving your family car. Eyes follow you from behind a slit in a translucent sheet. A tear, loosely sewn, cuts across an image. A nose emerges, and elsewhere faces float in repose, softened and semi-hidden. Overlays, cuts, and stitches in the smoky surface create a game of hide and seek. Perhaps we’ve caught someone mid-dream, but who? The person in the portrait or the artist herself?

Eyes follow you from behind a slit in a translucent sheet. A tear, loosely sewn, cuts across an image. A nose emerges, and elsewhere faces float in repose, softened and semi-hidden. Overlays, cuts, and stitches in the smoky surface create a game of hide and seek. Perhaps we’ve caught someone mid-dream, but who? The person in the portrait or the artist herself? There I was, sitting in a New Jersey Burger King, while the restaurant manager I was on a date shouted the lyrics to Rule, Britannia! at the top of his lungs. I had just started eating my Whopper meal when he started belting it out, his arms firmly placed on my shoulders. “She’s British! She’s British,” he shouted at the various people who were just getting on with their day, but were clearly wondering what on earth was going on. Well, this is going to be fantastic, I thought. I was in my mid-40s at the time, and had no real plan other than which states I would be visiting, placing newspaper adverts in New York, New Jersey, Los Angeles, Miami, and Philadelphia claiming to be a single woman looking for love.

There I was, sitting in a New Jersey Burger King, while the restaurant manager I was on a date shouted the lyrics to Rule, Britannia! at the top of his lungs. I had just started eating my Whopper meal when he started belting it out, his arms firmly placed on my shoulders. “She’s British! She’s British,” he shouted at the various people who were just getting on with their day, but were clearly wondering what on earth was going on. Well, this is going to be fantastic, I thought. I was in my mid-40s at the time, and had no real plan other than which states I would be visiting, placing newspaper adverts in New York, New Jersey, Los Angeles, Miami, and Philadelphia claiming to be a single woman looking for love. Jessica Winter in The New Yorker:

Jessica Winter in The New Yorker: